LINKED PAPER

Genetic analyses provide new insight on the mating strategies of the American Black Swift (Cypseloides niger). Gunn, C., Potter, K. M., Fike, J., Oyler-Mccance, S. 2023. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13147. VIEW

Reproduction is a key aspect of a bird’s life, but there are a number of different ways to go about it. While most birds are monogamous, at least socially, other possible mating strategies include polygyny, polyandry, and polygynandry. Understanding a species’ mating strategy is often crucial when making conservation or population management decisions, particularly for small populations and/or threatened species, but it can be difficult to classify based on observations alone. Molecular techniques have made it possible to accurately determine the parentage of individuals and thus the mating strategy at play, sometimes with surprising results.

In a 2023 study in Ibis, Carolyn Gunn and colleagues used genetic analyses to explore the mating system of the American Black Swift (Cypseloides niger borealis).

American Black Swift life history

Many swift species are assumed to be monogamous, and this has generally been considered to be the case for Black Swifts too. Field observations have suggested they exhibit strong nest-site fidelity, reuse the same nest-niches each year, and exhibit behaviours indicative of a stable pair bond with biparental care (summarised in Gunn et al. 2021). However, no previous studies have definitively investigated mating strategies or parentage in Black Swifts. In this study, the mating system of the Black Swift was explored using species-specific genetic markers in conjunction with banding data from six colonies in the western United States from 2004 to 2019.

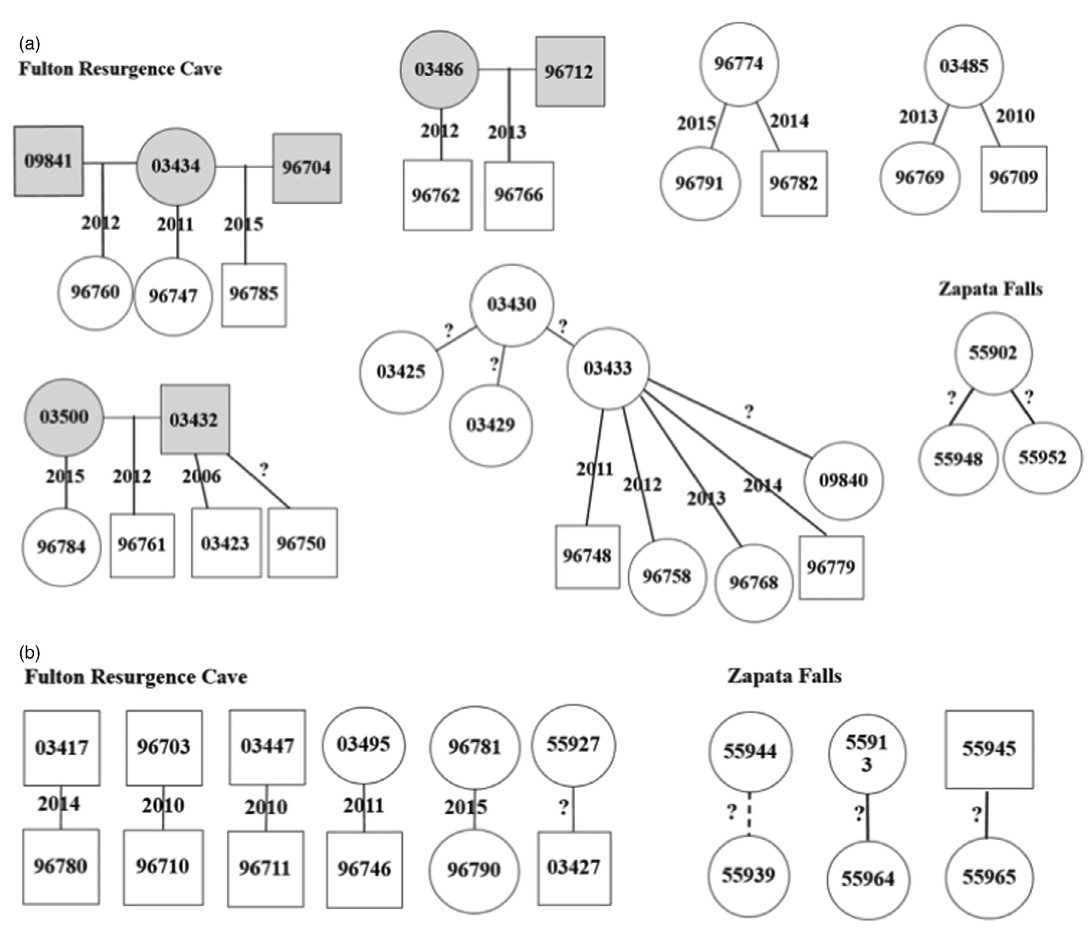

Figure 1. Relationships of Black Swift samples from Fulton Resurgence Cave and Zapata Falls genotyped at 10 microsatellite loci. (a) Parent–offspring relationships with more than one offspring (four identified parent pairs shaded in grey). (b) Parent–offspring relationships with only one identified offspring. Circles represent females and squares represent males. If the timing of the reproductive event is known, then the year is shown on the line between the parent and offspring. If the timing is unknown (which is the case when the offspring was captured as an adult), then it is represented by a question mark (?). If a parent pair is present, then the female and male are linked to each other with a horizontal line and the offspring is linked by a vertical line midway from the horizontal line. A dashed line indicates that it is unclear which is the parent and which is the offspring.

No evidence of multi-season biological parent pairs

The results found no biological parent pairs to last longer than one breeding season, suggesting that females are not sexually monogamous with a single partner for many years as hypothesised. The researchers offer a number of different explanations for this finding. Firstly, the mating system of this species may not be rigid, and previous observations of the same banded pair attending a nest annually for a number of years may represent just one of the strategies they use. It may also be that the male or female engages in serial monogamy, breeding and attending a nest with a partner for a single year and switching mates between breeding seasons due to ‘divorce’ or the death of their mate. Alternatively, females may engage in extra-pair copulation (EPC) resulting in extra-pair paternity (EPP) of the offspring despite the appearance of monogamy in a stable social pair. Although EPC was not visually confirmed in this study and only one report of EPP exists for swifts (Martins et al. 2002), molecular techniques have led to extra-pair offspring being reported in 90% of species, and over 11% of offspring in socially monogamous species are the result of EPP (Griffith et al. 2002).

Male parents were underrepresented in the results, despite genetic sampling being almost evenly divided between the sexes. This could be due to small sample size and sampling bias, but could also be explained by breeding season male dispersal from the colony post-mating, or sexual selection factors such as sperm competition in females that mate with multiple males (Birkhead 1998), or female preferences that affect breeding sex ratio and ecological factors such as population density (Jones & Ratterman 2009).

Further research would help to elucidate these findings, with one limitation of this study being the inability to permanently mark birds and capture adult pairs at their nest along with their offspring. Black Swifts are currently classified as Vulnerable, and are likely to continue to experience changing habitats and behaviours in the near future which could impact their mating strategies and their demographic and genetic dynamics, highlighting the need for further studies to aid in future conservation management decision-making.

References

Birkhead, T.R. (1998). Sperm competition in birds. Reviews of Reproduction 3: 123–129. VIEW

Griffith, S.C., Owens, I.P.F. & Thuman, K.A. (2002). Extra pair paternity in birds: a review of interspecific variation and adaptive function. Molecular Ecology 11: 2195–2212. VIEW

Gunn, C., Lowther, P.E., Collins, C.T., Beason, J.P., Potter, K. & Webb, M. (2021). Black Swift (Cypseloides niger). In Billerman, S.M. & Keeney, B.K. (eds) Birds of the World. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. VIEW

Jones, A.G. & Ratterman, N.L. (2009). Mate choice and sexual selection: what have we learned from Darwin? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 10001–10008. VIEW

Martins, T.L.F., Blakey, J.K. & Wright, J. (2002). Low incidence of extra-pair paternity in the colonially nesting common swift Apus apus. Journal of Avian Biology 33: 441–446. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: American Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) | Spring Fed Images | CC0 1.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here