LINKED PAPER

Remote tracking unveils intercontinental movements of nomadic Short-eared Owls Asio flammeus with implications for resource tracking by irruptive specialist predators. Calladine, J., Hallgrimsson, G.T., Morrison, N., Southall, C., Gunnarsson, H., Jubette, F., Sergio, F., Mougeot, F. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13304 VIEW

Short-eared Owls have long known to be nomadic, in search of their preferred, but often unpredictable small mammal prey. However, the truly impressive scale of their nomadism has become apparent only with the advent of tracking technology. Our aspirations to track these birds first materialised in about 2007. It was clear from an observational study that something unusual was happening. A small radio-tracking study in 2011 revealed some glimpses of their behaviour but highlighted even more unknowns and the need for more work and better technology. It took a while to find both a tag that would deliver what we needed and the money to buy them. In 2017, we successfully deployed GPS tags on our first cohort of five Short-eared Owls in Scotland, adding 12 more birds in the following three years. COVID-19, and its associated travel restrictions, tried its best to thwart our attempts to tag birds across a range of contrasting sites, but a fortuitous collaboration with Gunnar Þór Hallgrímsson of the University of Iceland saw a further 13 birds tagged in Iceland in 2020–22. A further partnership with Francois Mougeot at the University of Castilla-La Mancha, added another 17 Short-eared Owls in Spain in 2019–22, providing us with an impressive suite of birds spanning the latitudinal breeding range of the species in Europe.

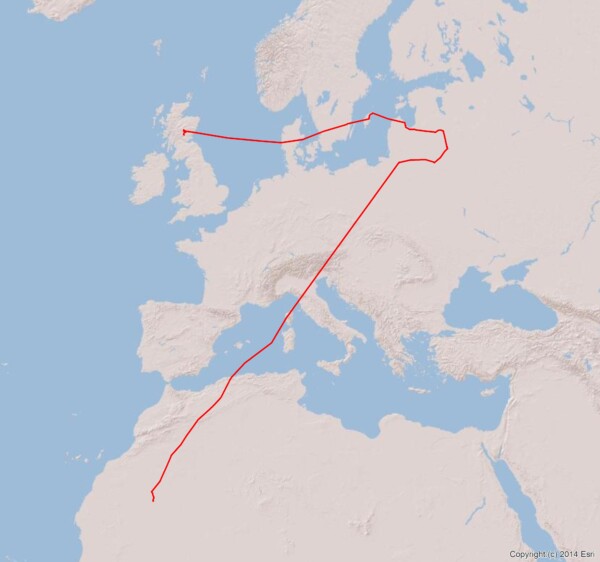

Figure 1. The movements across Europe and North Africa by 47 Short-eared Owls tagged in Iceland (Yellow), Scotland (Black) and Spain (Red) between 2017 and 2022.

Watching the data delivered by these tagged birds was an exciting privilege, and at times an emotional roller-coater. Each bird appeared to do different things. Furthermore, the same birds did very different things in different years. While fascinating, it was constantly on our minds that at some point we had to make sense of it all. Eventually, patterns began to emerge and it became apparent that the tagged birds’ wanderings could be divided into three categories:

- Movements around a home range – including breeding territories, these are where the owls spent most of their time. It is within the home ranges that we were best able to look at the habitats birds used – though that is a story for another time;

- Short distance movements – these can be progressive, sometimes meandering, steps from one home range to the next and probably account for most of the sightings of Short-eared Owls across the lowlands of Britain;

Figure 2. Searching for often unpredictable prey through frequently short and progressive movements took this Short-eared Owl, tagged in Scotland, across much of Britain and Ireland between July 2020 and October 2022.

- Long distance movements – despite these occupying the least of a Short-eared Owl’s time, they tend to be the most headline-grabbing movement category. Usually taking advantage of favourable weather conditions to set off on such movements, and with good tailwinds, we recorded owls sustaining average speeds of up to 70–80 kmh-1 (measured at ground level) over periods up to nine hours.

Figure 3. Long distance movements are not always direct or continuous. This bird travelled from Scotland to Mauritania via Latvia and Belarus, a route of at least 6,900 km accomplished over 40 days between September and November 2020.

Combinations of short exploratory movements with the occasional opportunistic long-distance leap contribute to the Short-eared Owls’ ability to find and exploit vole outbreaks – and their success as a nomad.

The surprising scale of the species’ nomadism was perhaps best shown by the distances between sequential nesting attempts by individual birds. Nine tagged owls, of both sexes, were monitored while nesting over two seasons and the distances between nest sites used in different years ranged from 41 km to a truly astonishing 4,216 km. Distances between nest sites in excess of 1,000 km were recorded by four of those nine birds! Two females nested about 250 m apart on the Isle of Arran in 2020. In 2021, one of those birds nested in Nordland, Norway and the other in the Pechora Delta, Russia – distances of 1,838 km and 3,131 km from their Arran nests, respectively. Other unexpected behaviours included most females departing the nest before their young were fully independent, leaving them to be reared by the males, and one female that nested in both Scotland and Norway in the same year.

A life history strategy which includes very large dispersal distances, including between sequential breeding locations, is successful in that the owls can track unpredictable prey resources in order to maximise their chances of rearing large broods. While successful – after all Short-eared Owls breed on four continents, regularly visit a fifth and have colonised some very isolated island groups – this lifestyle does appear to incur a cost to their individual survival; on average less than half of adults survive from one year to the next. So, travelling wide, breeding hard and, as a result, dying young, it is not a hedonistic lifestyle but one of altruism, in which an owl prioritises producing the next generation over its own survival.

Although widespread, numbers of Short-eared Owls are thought to be in decline but it has been challenging to interpret the often sparse and sporadic data for the species. New knowledge of the movements and life history strategy of Short-eared Owls now allows us to better understand the considerable challenges associated with the monitoring and therefore also conservation of such nomadic species. With a single, potentially integrated and highly mobile, population across most of Europe, actions to protect the species and its habitats would benefit from novel approaches, for example acoustic monitoring, and coordination at wide geographic scales.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the many individuals, charitable trusts and other organisations that contributed financially or otherwise helped with this study.

Image credits

Top right: A tagged Short-eared Owl hunts over a stand of lupins in Iceland © Gunnar Þór Hallgrímsson.

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here