Does feeding birds increase local nest predation?

LINKED PAPER

Provision of supplementary food for wild birds may increase the risk of local nest predation. Hanmer, H.J., Thomas, R.L. & Fellowes, M.D.E. 2016. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12432 VIEW

Across the world, providing food for garden birds is a huge source of pleasure for hundreds of millions of people. In more urbanised countries, bird feeding is the main way that city dwellers are able to actively engage with wildlife. It is difficult to exaggerate just how widespread this is; in our local area (Greater Reading, UK) over 55% of households feed wild birds (Orros & Fellowes 2015) and nationally the figure approaches 50%. The UK may well be at one extreme, but in the USA some 53M people feed birds in their gardens (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2014). The result is a huge perturbation experiment, where we in the UK as a nation add over 50,000 tonnes of supplementary food to our urban ecosystems every year, with a highly conservative estimate suggesting that we are providing enough food to maintain over 31M of our most common garden birds (Orros & Fellowes 2015a).

This is simply staggering, but the influence of such a common and widespread practice has received much less attention from researchers than it deserves. Evidence suggests that our urban avifauna has greatly changed in direct response to the provision of food. The poster child (bird?!) of this change is the European Goldfinch, Carduelis carduelis. In the 1970s, only 1% of gardens were visited by goldfinches, and now over 60% of gardens in the British Trust for Ornithology’s Garden Bird Watch survey record their presence. This is closely aligned with the enormous increase provision of specialist food, such as nyger seed. It is not only passerines which benefit from changes in the provision of supplementary food. In Reading, particularly during the breeding season, the town is visited by several hundred Red Kites, Milvus milvus, every day, where more than 1 in 25 households regularly provide meat for these magnificent raptors (Orros & Fellowes 2014, 2015b; see Mel’s excellent blog post here).

But is the provision of supplementary food always a good thing? While research has considered the effects of supplementary food on the breeding success and over-winter survival of urban birds, my supervisors (Professor Mark Fellowes and Dr Becky Thomas) and I were interested in asking about some indirect effects of attracting high densities of birds to predictable point sources of food. Our research group started by showing that numbers of insects were reduced near bird feeding stations (Orros & Fellowes 2012; Orros et al. 2014). A chance observation of a Great Spotted Woodpecker, Dendrocopos major, visiting a peanut feeder, and then flying to a nest box where it proceeded to hammer through the wood and then devour the Eurasian Blue Tit, Cyanistes caeruleus, chicks inside set us thinking as to whether, as with the insects, nesting close to bird feeders would result in increased predation. Feeders are frequently visited by Magpies and Grey Squirrels, both common nest predators in the UK.

This is tricky to study! We had understandable ethical qualms about placing feeders near wild bird nests, even if logistically we could find enough for meaningful statistical testing. Seeking correlations between nest success and feeder density is possible, but given the ubiquity of feeding in the UK it would be difficult to isolate variance that was not entangled with socioeconomics and differences in habitat quality, but this approach could work in areas where feeding is less common. Instead we took an experimental approach using artificial nests, each continually monitored by camera traps to record every predation event.

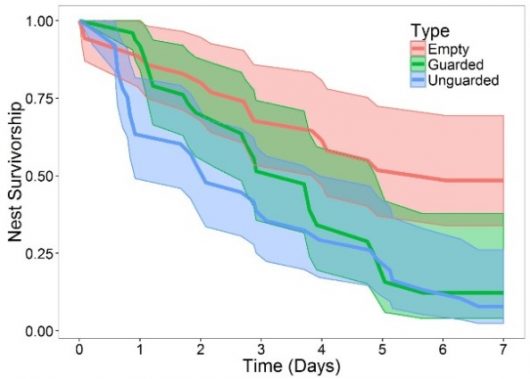

Using our suburban parkland campus at Reading, we set up over 100 wire and grass ‘nests’ in sites mimicking where Eurasian Blackbirds, Turdus merula, would nest. Each was baited with two quail eggs. The nests were 5 and 10m away from the feeding station, to replicate typical suburban garden size. The feeders were either empty or filled with peanuts, and the filled feeders were either of a standard open design, or surrounded by a guard designed to prevent access by larger species such as squirrels and corvids. The feeders were also monitored by camera traps, so we could see what species visited them.

Not surprisingly, almost no visits were made to empty feeders. Unguarded feeders were frequently visited by Eurasian Magpies, Pica pica, but Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, dominated. Guarded feeders received relatively few visits from Magpies, and Grey Squirrel visits were also much reduced, but small passerines were now able to access food without being excluded.

Did nesting adjacent to a feeder matter? Around 50% of nests placed near empty feeders survived a week’s placement, but only around 10% of those near filled feeders were not predated, a five-fold difference in predation rate. Unexpectedly, the presence of a feeder guard did not make a significant difference. This is a substantial increase in predation, and Magpies and Grey Squirrels to a lesser extent were common nest predators. What was less expected was that Eurasian Jays, Garrulus glandarius, were also important nest predators, even though they didn’t visit the feeders. Our suspicion is that the Magpies and Grey Squirrels are attracted to the food, and then forage locally, increasing the chances of finding local nests, and that the Jays respond to the presence of the other species, rather than the presence of the food itself. Irrespective of the behavioural underpinning, the result of providing food was increased nest predation.

People who feed birds do so because they wish to help them, but may inadvertently be causing harm. So, should we stop feeding birds during the breeding season? We would certainly not advise that given the evidence for a net positive effect on bird populations, and the benefits of feeding go beyond the direct effects on bird populations, but it also helps bring people closer to birds and nature. The amount of pleasure hundreds of millions of people get from feeding backyard birds is an enormous enhancement to our well-being and connection to wildlife on a global scale. Instead, we’d suggest that feeders are placed as far away as possible from potential nests sites during that key time in late spring, that we offer food which is less attractive to nest predators and more suitable for the birds we want to support, and we would still advocate the use of feeder guards, even though this didn’t reduce predation. This is simply because the use of guards means that more food goes to the target beneficiaries, rather than helping grow local populations of squirrels and Magpies!

References

Orros, M.E., and Fellowes, M.D.E. 2012. Supplementary feeding of wild birds indirectly affects the local abundance of arthropod prey. Basic and Applied Ecology 13: 286-293. VIEW

Orros, M.E., and Fellowes, M.D.E. 2014. Supplementary feeding of the reintroduced Red Kite Milvus milvus in UK gardens. Bird Study 61: 260-263. VIEW

Orros, M.E., and Fellowes, M.D.E. 2015a. Wild bird feeding in a large UK urban area: characteristics and estimates of energy input and individuals supported. Acta Ornithologica 50: 43-58. VIEW

Orros, M.E., and Fellowes, M.D.E. 2015b. Widespread supplementary feeding in domestic gardens explains the return of reintroduced Red Kites Milvus milvus to an urban area. Ibis 157: 230-238. VIEW

Orros, M.E., Thomas, R.L., Holloway, G.J., and Fellowes, M.D.E. 2015. Supplementary feeding of wild birds indirectly affects ground beetle populations in suburban gardens. Urban Ecosystems 18: 465-475. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: A squirrel visiting a garden feeder © Arwen_7 used under Creative Commons CC BY-SA 2.0

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.