LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Divergent foraging habitat preferences between summer-breeding and winter-breeding Procellaria petrels. Bentley, L.K., Manica, A., Dilley, B.J., Ryan, P.G. & Phillips, R.A. 2022 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13152 VIEW

Mapping the distributions of highly mobile species is important for understanding their ecology and improving conservation outcomes. A key driver of where animals go is the search for food, and many animals undertake challenging foraging trips working around various ecological constraints. Pelagic seabirds are a great example of this: during the breeding season they leave their nesting islands (where their partner remains incubating their egg) and forage in the open ocean, making trips that can cover thousands of kilometres in up to a fortnight. The need to build up energy stores for themselves, and then return to their nest and partner means that we would expect foraging behaviour to be as efficient as possible. Seabirds are likely to encounter various anthropogenic threats (most likely commercial fishing vessels) on their foraging trips: it is therefore important that we understand where they are going, and the types of habitats that they target when looking for food.

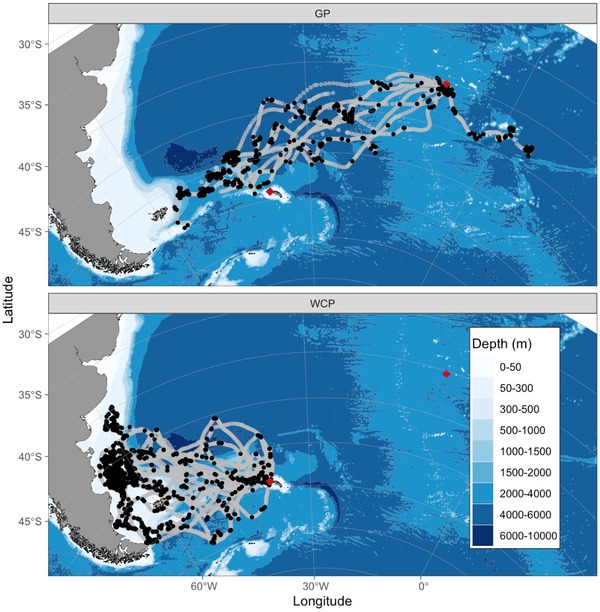

Procellaria is a genus containing five species, two of which (White-chinned Petrels Procellaria aequinoctialis and Grey Petrels P. cinerea) are among the most bycaught species in the Southern Ocean. These two species breed on multiple subantarctic islands, while the other three members of the genus are all endemic to single nesting locations. White-chinned Petrels breed during the austral summer, like most seabirds, while Grey Petrels have a far less common strategy: breeding during winter. We GPS tracked incubating Grey and White-chinned Petrels from their largest populations in the South Atlantic, Gough Island and South Georgia, respectively. All bar one of the Grey Petrels foraged near South Georgia, in an area completely overflown by their congener in the summer months. Instead, White-chinned Petrels foraged in the shallow waters off the Patagonian Shelf.

Figure 1 Tracks of Grey Petrels (GP) from Gough Island (austral winter), and White-chinned Petrels (WCP) from South Georgia (austral summer) tracked during incubation. Map generated using tools from the ggOceanMaps R package. Bathymetry layer from NOAA.

When looking at the oceanographic characteristics of the area each species chose to forage in, we saw a clear preference in White-chinned Petrels for shallow, warm water, while Grey Petrels preferred deep, cool water. Both species demonstrated a commuting phase and then a foraging phase at the most distant end of their tracks. It is likely that White-chinned Petrels travel so far from their colony (~2000 km), at least in part, due to the high levels of interspecific competition around South Georgia during the summer breeding season. The total population of breeding seabirds on the island is likely more than 30 million pairs. This has led to spatial partitioning of foraging habitats across multiple axes, and birds demonstrating multiple types of prey specialisation.

Interestingly, all bar one of the Grey Petrels travelled from Gough Island to an area north-north-west of South Georgia. This is over 3000 km away from Gough, despite it being a time of year when local competition is presumed to be low: far fewer species breed on Gough Island during winter. It may be that due to poor local conditions the areas near South Georgia represent the Grey Petrels’ most profitable foraging grounds, despite the long commute. It is hypothesised that low food availability close to Gough Island is responsible for the slow growth rates of Grey Petrel chicks at this location.

Figure 2 Grey Petrel (Procellaria cinerea) in flight, East of the Tasman Peninsula, Australia © JJ Harrison CC BY SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons.

The habitats chosen by these two species are distinct, and their breeding allochrony is marked (3-4 months between laying). However, of course, these populations are from different breeding islands. Further study that investigates habitat preferences where the species breed in sympatry (Marion, Crozet, Kerguelen, or New Zealand) can help us better understand the consistency and flexibility of habitat preferences at a species level, as well as shed further light on the causes of winter breeding.

Image credit

Top right: White-chinned Petrel (Procellaria aequinoctialis) © Ed Dunens CC BY 2.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.