LINKED PAPER

Icelandic whimbrel first migration: non-stop until West Africa, yet later departure and slower travel than adults. Carneiro, C., Gunnarsson, T.G., Kaasiku, T., Piersma, T., Alves, J.A. 2023. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13282. VIEW

Bird migration is a truly captivating natural wonder, especially the mystery surrounding how young, inexperienced birds, often just a few weeks old, manage to embark on and navigate long-distance flights.

What do we know about Icelandic whimbrel migration?

A large proportion of world’s whimbrel breed in Iceland (last estimate: 256,000 pairs; Skarphéðinsson et al. 2016), and over the past 11 years, we have dedicated efforts in learning more about them. As for their migration, a crucial part of their annual cycle, it is now clear that nearly always individuals embark on a non-stop flight after leaving Iceland, covering an impressive distance of 5000-6000 km in one go to reach their wintering grounds in West Africa (Alves et al. 2016; Carneiro et al. 2019a). The timing of their departure from Iceland exhibits some variability, as it can depend on the preceding breeding success (Carneiro et al. 2019b; 2023).

When it comes to spring migration, the story is different. Whimbrels depart from their wintering sites on nearly the same date each year, but with a different plan (Carneiro et al. 2020). They either make a non-stop flight back to the breeding grounds (i.e., similar to autumn migration), or, more commonly, they fly to a stopover area where they stay for 1-2 weeks before making the final leg of the journey to Iceland (Carneiro et al. 2019ab). All of this is what adults do. But what about juveniles? When do they depart Iceland? Do they fly straight to West Africa too? How do they know the way? We know that juveniles do not migrate with their parents, but do they join other adults?

Figure 1. Juvenile Icelandic whimbrel, tagged with a GPS/GSM tracker from Global Messenger © Triin Kaasiku.

Juvenile whimbrel migration

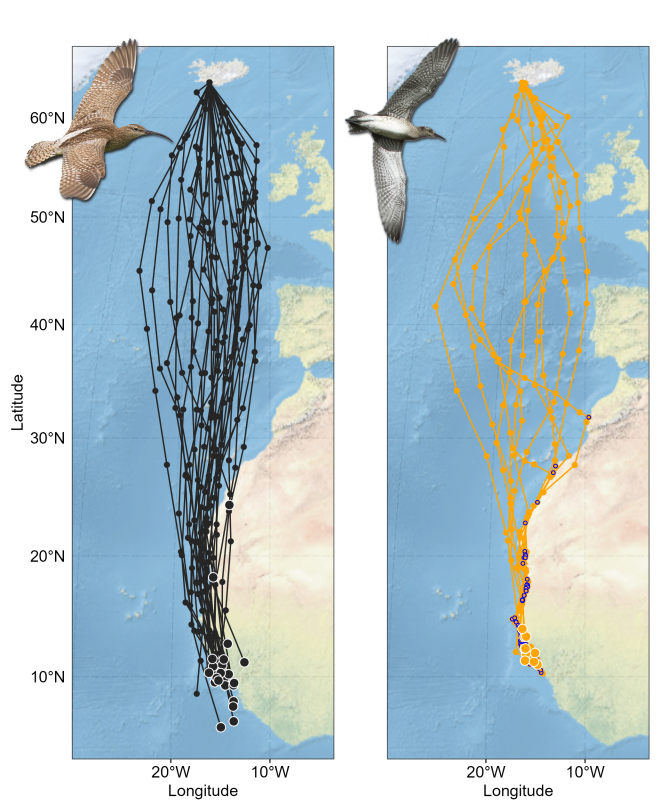

While adults may constitute the core of the population, it is the juveniles that may hold the key to the population’s ability to adapt to environmental changes (Gill et al. 2019). To learn about the migration of juvenile whimbrel, we deployed GPS trackers on 13 birds, just when they started to learn how to fly, during the breeding seasons of 2021 and 2022 (Figure 1). These GPS trackers recorded the geographical locations of the birds each 6 hours and transmitted them to us via the GSM network. Some weeks later, we could see their migrations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Autumn migrations of adult (left) and juvenile (right) Icelandic whimbrel. The large filled circles with a white outline represent the wintering sites: the blue circles on the right panel represent juvenile stopover locations © Tómas G. Gunnarsson (left) and Triin Kaasiku (right).

Results – in “science poetry”

It is a common observation that researchers often employ a distinct set of terminology and sentence structures that might not be easily comprehensible to readers outside the academic sphere. On the 1st of October 2023, at the annual conference of the International Wader Study Group, I had the pleasure of listening to Mary Colwell, a writer renowned for her deep passion for the natural world and her efforts to preserve it. After two days of a dense program of scientific presentations, many on nature conservation issues, she challenged the researchers in the audience to tell those same stories, but this time using only words found in poems. In this manner, our findings could resonate far beyond academia, bridging the gap to a broader audience. This could be a great way to share the Icelandic whimbrel juvenile migration story, but my (inexistent) poetic abilities do not allow me. However, I wondered whether the ChatGPT tool could help. I asked it to transform the scientific paper abstract into a poem. Surely it did, in just 2 or 3 seconds! This is the poem:

“Migratory behaviour in youth, a wondrous sight,

Complex resources guide their daring flight,

From molecules to learning, social and free,

A journey’s genesis, a marvel to see.

Icelandic whimbrels, youthful and bold,

To West Africa’s warmth, their tales unfold,

Like their elders, they take to the air,

But differences emerge in this skyward affair.

They depart a bit later, paths not so straight,

With more stops along, a different rate,

Their travel’s slower, a distinctive style,

Youth’s unique touch, mile after mile.

Departure dates vary, Iceland’s grand stage,

A model to study, a migration’s new page,

In this annual routine, by nature’s design,

The ontogeny of migration, a story so fine.”

In my opinion, it sounds good. And it encompasses the main findings in the paper (in bold):

- Like adults, juvenile whimbrels make a long-distance flight to West Africa.

- Juveniles depart later than adults and make less straight flights.

- Juveniles stop more often than adults before reaching the wintering site, which results in a slower travel speed.

The comparison of adult and juvenile migrations, particularly the departure dates, suggests that at least late juveniles are unlikely to migrate in flocks containing experienced adult birds. Hence, it is improbable that these individuals learn the way to Africa first hand, but we cannot exclude the possibility of other social cues gathered prior departure. We finish the paper reasoning why the Icelandic whimbrel is an exceptional ‘developmental system’ (sensu Oyama et al. 2001) to investigate the roles of various developmental factors on the ontogeny of migration.

References

Alves, J.A., Dias, M.P., Méndez, V., Katrínardóttir, B. & Gunnarsson, T.G. 2016. Very rapid long-distance sea crossing by a migratory bird. Scientific Reports 6:38154. VIEW

Carneiro, C., Gunnarsson, T.G. & Alves, J.A. 2019a. Faster migration in autumn than in spring: seasonal migration patterns and non-breeding distribution of Icelandic whimbrels Numenius phaeopus islandicus. Journal of Avian Biology 50. VIEW

Carneiro, C., Gunnarsson, T.G. & Alves, J.A. 2019b. Why Are Whimbrels Not Advancing Their Arrival Dates Into Iceland? Exploring Seasonal and Sex-Specific Variation in Consistency of Individual Timing During the Annual Cycle. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7. VIEW

Carneiro, C., Gunnarsson, T.G. & Alves, J.A. 2020. Linking Weather and Phenology to Stopover Dynamics of a Long-Distance Migrant. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8. VIEW

Carneiro, C., Gunnarsson, T.G. & Alves, J.A. 2023. Annual Schedule Adjustment by a Long-Distance Migratory Bird. The American Naturalist 201. VIEW

Gill, J.A., Alves, J.A. & Gunnarsson, T.G. 2019. Mechanisms driving phenological and range change in migratory species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374. VIEW

Oyama, S., Griffiths, P. & Gray, R.D. 2001. Introduction: What is Developmental Systems Theory? In: Cycles of Contingency: Developmental Systems and Evolution (S. Oyama, P. Griffiths, & R. D. Gray, eds), pp. 1–11.

Skarphéðinsson, K.H., Katrínardóttir, B., Guðmundsson, G.A. & Auhage, S.N.V. 2016. Mikilvæg fuglasvæði á Íslandi.

Image credit

Top right: Eurasian Whimbrel © Axel Kristinsson BY CC SA 2.0 Wikimedia.