LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Factors influencing prevalence and intensity of Haemosporidian infection in American Kestrels in the nonbreeding season on the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Frixione, M. G., & Rodríguez-Estrella, R. 2023 Journal of Raptor Research. doi: 10.3356/JRR-22-74 VIEW

In North America, diverse groups of birds have migratory patterns that extend throughout Canada, the United States and Mexico. Among these groups of migrating birds, the most unknown for their dispersal and eco-biogeographic characteristics, are the raptors. Diverse information exists about these species and their movements in Canada and the United States, but there is scarce information about the connection of raptors between these countries and Mexico.

The migratory patterns of these raptors transcend borders when the reproductive season is over, and thousands of individuals of different species of raptors begin their migrations southward escaping winter conditions and settling in southern USA and Mexican lands where they spend their non-breeding season.

One of these wintering sites is the peninsula of Baja California, where during October and November several species of raptors increase their densities due to travelers from Canada and the United States, in some cases increasing the abundance of these species by three folds in the area. In addition to migratory raptors, these species also have resident populations that reproduce and remain in the area throughout the year.

During the fall and winter, both migratory and resident populations share the habitats of the peninsula. Once overwintering is finished (March-April), migratory raptors return to the areas of Canada and the United States to reproduce. This concentration of raptors throughout the peninsula during fall and winter is inserted in a complex ecological system where these species act as controllers of potential pests, including rodents and insects, which can generate complications for production and potential problems related to agriculture. Certain species of rodents and insects may be harmless to the ecosystem when population numbers are in balance, but when the supply of food exceeds their needs, population growth can transform them into a potential problem.

The biological control generated by these raptors in a complex system of migratory and resident birds has been scarcely studied. Among the species of raptors that present this type of pattern we have the American Kestrel (Falco sparverius); the species is distributed throughout the American continent and is known that populations in Canada and the United States have been steadily declining over past decades.

Figure 1 American Kestrel (migratory male) captured in March 2020 in an agriculture area in Baja California Sur, in northwestern Mexico.

We conducted several studies which involved the species in an agroecosystem of Baja California peninsula in Mexico during the breeding and overwintering season. Studies were focused in the breeding diet, and occurrence of parasites in the resident and overwintering migratory populations that arrives seasonally from northern areas to the peninsula during fall.

The use of these agricultural environments can expose resident and migratory individuals to different types of pathogens and their vectors that can be mostly acquired in these areas. In the case of the American Kestrel we have found that both resident and migratory individuals were infected by hemoparasites, some of them related to the avian malaria, the result of infection by dipterans, which reproduce in humid environments generated by human activities related to agriculture in the desert.

Figure 2 The author after captured a resident male in the edge of a native vegetation patch in an agroecosystem of Baja California Sur during November 2018, in northwestern Mexico © Abelino Cota Castro.

Sometimes parasites can affect part of the overwintering kestrel populations, for example other parasites such as the blood sucking fly, an ectoparasite dipteran which it hides under the plumage and feeds on the blood of kestrels affect mostly larger kestrels (highly probable migratory), which use agricultural habitats in contrast with smaller resident kestrels which forage in native vegetation areas covered by the Giant Cardon (Pachycereus pringlei). This blood sucking fly is known to be a carrier of the West Nile Virus, and other diseases of zoonotic potential. Although the occurrence of this fly has been recorded in a few individuals, the potential increase of this fly in the species could be of greater importance.

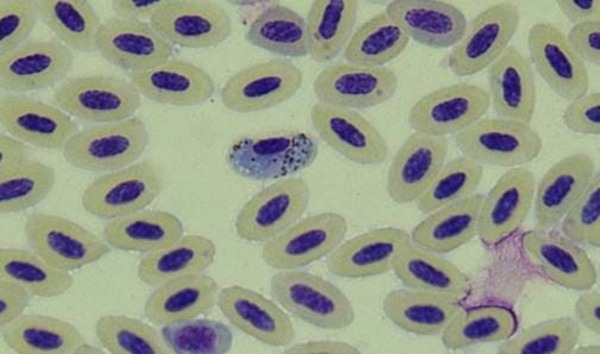

Figure 3 Hemoparasite infecting an erythrocyte in blood of an American Kestrel captured in Baja California Sur, in northwestern Mexico. Note the presence of malarial pigment and the displacement of the nucleus to the side in the infested erythrocyte.

This fly was not recorded in past research in the American Kestrel in the area. It should be noted that these studies on this ectoparasite should be monitored in the future focusing on the flows of individuals throughout North America. So far the flow of these ectoparasites carried by raptor hosts is unknown, and it is vital to understand these movements in North America through migratory raptors attracted by agroecosystems. In a context of opportunities and damages, we find that kestrels could be exposed to a delicate balance, attracted by food offerings however being exposed to threatening parasites. Further studies should be conducted on the flow of parasites and pathogens throughout the continent by expanding the focus to the community of migratory raptors that seasonally travel along North America.

References

Battin, J. 2004. When good animals love bad habitats: ecological traps and the conservation of animal populations: ecological traps. Conservation Biology 18:1482-1491. VIEW

Farajollahi, A., Crans, W.J., Nickerson, D., Bryant, P., Wolf, B., Glaser, A. & Andreadis, T.G. 2005. Detection of West Nile virus RNA from the louse fly Icosta americana (Diptera: Hippoboscidae). Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 21:474-476. VIEW

Frixione, M. G., & Rodríguez-Estrella, R. 2020. Trophic segregation of the Burrowing Owl and the American Kestrel in fragmented desert in Mexico. Journal of Natural History 54:2713-2732. VIEW

Smallwood, J.A & Bird, D.M. 2002. American Kestrel: Falco sparverius. Birds of North America.

Tella J.L., Rodríguez-Estrella, R. & Blanco, G. 2000. Louse flies on birds of Baja California. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 36:154-156. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Charles J. Sharp CC BY SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.