Conserving an endangered island parrot

LINKED PAPER

Evidence of evolutionary distinctiveness and historical decline in genetic diversity within the Seychelles Black Parrot, Coracopsis nigra barklyi. Jackson, H.A., Bunbury, N., Przelomska, N. & Groombridge, J.J. 2016. Ibis: DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12343. View

Parrots have recently been recognised as the most threatened of all bird groups (Olah et al. 2016). With 28% of extant parrot species (111 out of 398) classified as threatened by the IUCN, parrots face a much higher risk of extinction compared to any other bird group, (56% of parrots are currently in decline).

Fourteen of the 16 extinct parrot species occurred on islands. Such oceanic islands are home to some of the richest forms of biodiversity on the planet (Whittaker & Fernandez-Palacios 2007), but unfortunately, endemic island species are accurately vulnerable to human impacts and risk of extinction (Frankham 2005; Olah et al. 2016). Many island species are therefore high priority for conservation efforts (Cronk 1997), and conservation managers, who are tasked with recovering island endemic populations, must not only understand a species ecology, but understand its evolutionary history, to identify and retain genetic diversity, crucial for enhancing a species survival.

The Western Indian Ocean was once a rich source of parrot diversity with seven endemic island species once found across the Mascarenes and Seychelles. Sadly, five of these parrot species are now extinct leaving only two species remaining in the Indian Ocean today; the Mauritius parakeet, and the Seychelles Black Parrot.

Despite being the national bird of the Seychelles, the Seychelles Black Parrot (Coracopsis nigra barklyi) also one of the rarest endemic bird species. With an estimated population size of just 520-900 individuals (Reuleaux et al. 2013), the Seychelles Black Parrot is currently classified as vulnerable by the IUCN. Restricted to the small (38 km2) island of Praslin, Black Parrots are found in their highest densities in mature palm forest, including the UNESCO World Heritage site, Vallée de Mai. Black Parrots play an important role as a flagship species for the Vallée de Mai, which is a rare habitat containing all six palm species endemic to the Seychelles, including the endangered coco de mer. This palm forest forms a substantial part of the Black Parrot’s diet and nesting habitat (Reuleaux 2011; Reuleaux et al. 2014a, b).

Field survey records documenting a decline in population size and a history of possible range contraction have raised concerns about whether the Black Parrot is now genetically impoverished. Small isolated populations are often susceptible to detrimental genetic problems such as a loss of genetic diversity, the accumulation of deleterious alleles, inbreeding depression and loss of evolutionary potential (the ability to adapt to changing environments). Combined, these effects may increase the risk of extinction for the Seychelles Black Parrot.

To evaluate the conservation status of the Seychelles Black Parrot, and provide important guidance for ongoing conservation management by the Seychelles Islands Foundation, the Public Trust which manages the Vallée de Mai, this study combined molecular and morphological data to explore the Seychelles Black Parrots’ evolutionary history in terms of their genetic and morphological distinctiveness from other subspecies of Black Parrot found on Grand Comoros (C. n. sibilans) and Madagascar (C. n. nigra & C. n. libs), whilst quantifying levels of genetic diversity within the population over time.

A distinct evolutionary trajectory

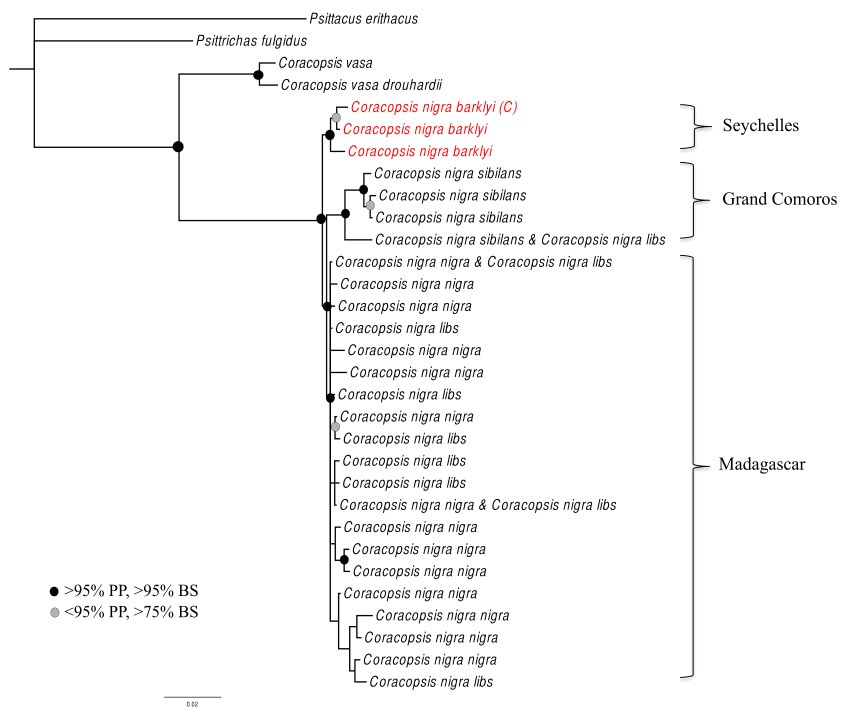

Genetic data obtained from museum specimens of Black Parrot from the Seychelles, Grand Comoros and Madagascar were used to reconstruct their evolutionary history. Excitingly, our phylogenetic reconstruction demonstrates that the Seychelles Black Parrot forms a distinct sister clade which appears to be on a different evolutionary trajectory compared with the subspecies found on Grand Comoros and Madagascar (Fig. 2).

This unique evolutionary trajectory was also detected during our examination of patterns of genetic structure and clustering among the four Black Parrot subspecies. The Seychelles Black Parrots were predominately assigned to a single unique cluster, whilst Black Parrots from Comoros and Madagascar were assigned to two different clusters (Fig 3).

Size matters: differences between islands

These genetic findings were supported by our examination of morphological data. Five comparable measurements were obtained from museum specimens at the Natural History Museum at Tring, UK and a number of other European museums. Significant morphological differences were observed between Black Parrot subspecies from different islands. Interestingly, total body size was the predominant variable for discriminating between subspecies, with the Seychelles Black Parrot being the smallest of the four subspecies. Body size appears to have increased as the Black Parrot has radiated from the Seychelles and Grand Comoros onto Madagascar.

Drops in levels of genetic diversity and effective population size over time

We were able to explore whether the current population of Seychelles Black Parrots have become genetically impoverished by comparing levels of genetic diversity from museum specimens (dating back to 1878) with contemporary samples collected in the field. A loss of genetic diversity was observed across a number of diversity measures (Fig. 4), suggesting the current population may have undergone a population bottleneck (reduced to a small size) as a result of range contraction and habitat loss.

(click on image for larger view)

Genetic data also allows conservation biologists to measure effective population size (Ne). This is a reflection of the number of birds contributing offspring to the next generations’ gene-pool, (in light of reduced levels of genetic diversity as per Fig. 4). Effective population size is often smaller than consensus size taking into account overlapping generations, fluctuating population size and the breeding sex ratio of the population. For the Seychelles Black Parrots, we observed a severe decline in Ne over the last 146 years, from 864 in 1878 to just six by 2011 (Fig. 5).

Outcomes for conservation

Whilst many of the findings in this study shed a worrying light on the genetic health of the current Seychelles Black Parrot population, evidence of its evolutionary and morphological distinctiveness, in combination with years of intensive research into its unique ecology and behaviour, have led to this parrot being recently reclassified to full species status (Coracopsis barklyi; del Hoyo et al. 2015). This is a huge step forward for conservation, providing much needed data and support for intensive management, whilst highlighting the importance of such efforts to ensure this endemic parrot does not join the numerous extinct parrot species now only found in museums, but remains a part of the Seychelles unique biodiversity and cultural heritage forever.

References

Cronk, Q.C.B. 1997. Islands: stability, diversity, conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 6: 477-493. View

del Hoyo J., Collar N.J., Christie D.A., Elliot A. & Fishpool L.D.C. 2015. HBW and Birdlife International Illustrated Checklist of The Birds of the World 1. Lynx Editions, UK.

Frankham, R. 2005. Genetics and extinction. Biol.Conserv. 126: 131-140. View

Olah, G., Butchart, S.H., Symes, A., Guzmán, I.M., Cunningham, R., Brightsmith, D.J. & Heinsohn, R. 2016. Ecological and socio-economic factors affecting extinction risk in parrots. Biodivers. Conserv. 25: 205-223. View

Reuleaux, A. 2011. Population, feeding and breeding ecology of the Seychelles black parrot (Coracopsis nigra barklyi). MSc thesis, University of Göttingen.

Reuleaux, A., Bunbury, N., Villard, P. & Waltert, M. 2013. Status, distribution and recommendations for monitoring of the Seychelles black parrot Coracopsis (nigra) barklyi. Oryx. 47: 561-568. View

Reuleaux, A., Richards, H., Payet, T., Villard, P., Waltert, M. & Bunbury, N. 2014a. Insights into the feeding ecology of the Seychelles black parrot Coracopsis barklyi using two monitoring approaches. Ostrich. 85: 245-253. View

Reuleaux, A., Richards, H., Payet, T., Villard, P., Waltert, M. & Bunbury, N. 2014b. Breeding ecology of the Seychelles Black Parrot Coracopsis barklyi. Ostrich. 85:255-265. View

Whittaker, J.M. & Fernández-Palacios, J.M. 2007. Island Biogeography: Ecology, Evolution and Conservation (Second Edition). Oxford University Press, UK.

Image credit

Featured image: Seychelles Black Parrot Coracopsis nigra barklyi © Seychelles Islands Foundation

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.