Where do European Nightjars go?

LINKED PAPER

Migratory pathways, stopover zones and wintering destinations of Western European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus. Evens, R., Conway, G.J., Henderson, I.G., Cresswell, B., Jiguet, F., Moussy,Sénécal, D., Witters, N., Beenaerts, N. & Artois, T. 2017. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12469. VIEW

Bird migration might be one of the most fascinating annual events. Every autumn, while billions of birds attempt to bridge the gap between breeding and wintering areas, my research sites are going silent too, and for years we have been asking ourselves: “Where do ‘our’ birds go?”

We have come a long way from thinking that birds hibernate at the bottom of the sea or turn into mice. We also don’t need a ‘Pfeilstorch’ anymore to bring back a body-piercing arrow from Central-Africa to reveal its wintering site. Today, we rely on science, technology and worldwide bird-migration-counts to answer migration-related questions. Yet, despite technological advances, migration routes and wintering destinations of most light-weight bird species still haven’t been fully discovered.

The European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus is such a light-weight (70g), long-distance, trans-equatorial migrant, protected under the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. It breeds on dry sandy soils in Eurasia, mainly in open semi-natural habitats, such as heathlands. Although adult Nightjars have a high fidelity to breeding sites, recovery rates of ringed Nightjars in their non-breeding areas are extremely low, with just two found in Africa, out of a total of 131 recoveries globally, up until 2009.

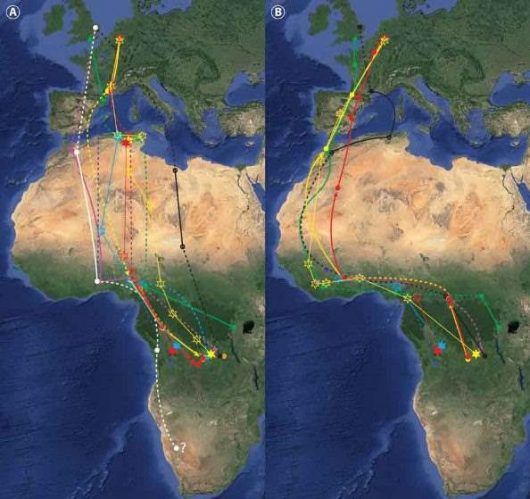

It was generally assumed that Nightjars’ wintering range was split into two major regions: the first extending along the eastern coast of Africa from Kenya to South Africa and the second in the western Sub-Saharan region from Senegal to Cameroon. In 2013, a geolocator study by Cresswell and Edwards led to the discovery of new wintering sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the identification of a possible loop-migration pattern. To answer some of the remaining migration-related questions, we used a combination of geolocators and GPS-loggers to reconstruct the migration of eleven Western-European Nightjars. We also tagged one juvenile Nightjar, and we were very fortunate to recapture this bird two years later. Luckily for us, it was still carrying its geolocator which contained information on two full migration routes.

Our Nightjars followed a loop-migration pattern which was consistent among individuals from five Western European sites. This implies that Nightjars follow different trajectories during autumn and spring migration, making an elaborate detour through Western Africa in spring. All Nightjars overwintered south of the Central African Tropical Rainforest in two sub-tropical ecoregions (Southern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic, Central Zambezian Miombo woodlands), outside their formerly-presumed wintering range. GPS-data also confirms that our Nightjars are stationary during the entire winter and stay in a distinct, small habitat patch. Surprisingly, the juvenile Nightjar also showed the capability of locating stopover zones and wintering areas, used by other, adult Western European Nightjars. During its second migration, it then located these specific areas again.

Every year, birds manage to cover great distances towards southern wintering areas. They consume enormous amounts of energy in order to cross ecological barriers, such as the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara. Consequently, refueling is also an important aspect of migration. We observed that Nightjars convergence near common stopover zones in Northern, Central and Western Africa, where our birds stayed for two to three weeks. These zones are situated in areas with a high-normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). Therefore, it seems plausible that Nightjars track seasonal rains in these regions in order to profit from the emergence of aerial insects. Based on our observations, we also dare to hypothesise that the Central African Tropical Rainforest is an ecological barrier for Nightjars too.

Nightjars use the same stopover sites as several other European migrants such as Common Swift Apus apus, Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus, and European Roller Coracias garullus. This indicates the importance of these specific zones and highlights the vulnerability of Western European bird populations to habitat destruction en route, and/or to a mismatch between arrival times and food availability caused by climate change.

We now known “where our Nightjars go”, but I also dare to dream about studying other aspects of Nightjars’ migration ecology in the future. Let’s hope we can answer other kinds of questions soon, such as “what is their behaviour during winter?”, “how do breeding populations spread across Nightjars’ wintering range?” or “why do they select certain stopover sites during migration?”.

References and further reading

Cresswell, B. & Edwards, D. 2013. Geolocators reveal wintering areas of European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus). Bird Study 60: 77–86. VIEW

Evens, R., Conway, G. J., Henderson, I. G., Cresswell, B., Jiguet, F., Moussy, C., Sénécal, D., Witters, N., Beenaerts, N. & Artois, T. 2017. Migratory pathways, stopover zones and wintering destinations of Western European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12469. VIEW

Evens, R., Beenaerts, N., Witters, N. & Artois, T. 2017. Repeated migration of a juvenile European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. Journal of Ornithology. DOI: 10.1007/s10336-017-1459-2. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Roosting European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus © Ruben Evens

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.