LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Preen oil composition of Pied Flycatchers is similar between partners but differs between sexes and breeding stages. Gilles, M., Fokkema, R.W., Korsten, P., Caspers, B.A. & Schmoll, T. 2023 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13246 VIEW

Using preen oil as a proxy of bird odour

Birds have a specialized gland located at the base of the tail, the uropygial (preen) gland. This gland produces a waxy secretion, called preen oil, which birds spread on their plumage during preening. Preen oil has diverse functions, like plumage maintenance and protection against ectoparasites. But preen oil also has odour-based functions. Preen oil is indeed an important source of the body odour of birds, and may have a role in olfactory communication (e.g., sex signalling during mate choice) and olfactory crypsis (i.e., chemical camouflage against nest predators) (reviewed in Grieves et al. 2022) and summarized in a BOU blog.

Figure 1 Sampling preen oil from a Pied Flycatcher © Tim Schmoll.

What information is encoded in the odour of flycatchers?

Studies on olfactory communication in birds are accumulating. Pied Flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) have been used in many studies on mate choice and sexual selection, yet no study has ever considered the potential role of odours for communication in this species.

The aim of our study was to describe the body odour of Pied Flycatchers and investigate whether it encodes socially-relevant information (similarity between partners, sex differences, differences between breeding stages, individual signatures). To do so, we sampled the preen oil of Pied Flycatchers breeding in nestboxes in Northwest Germany. The chemical analysis of the preen oil samples with GC-MS (gas chromatography-mass spectrometry) revealed interesting patterns:

- High similarity between breeding partners, which could mean that partners smell alike. This could be the result of partners sharing the same environment (e.g. having a similar diet, transferring preen gland microbes to one another). Alternatively (although unlikely), Pied Flycatchers may mate preferentially with individuals that have a similar odour to their own.

- Differences between females and males. The sex differences (e.g., higher volatility in females) were small but may be sufficient to be used for sex signalling during mate choice.

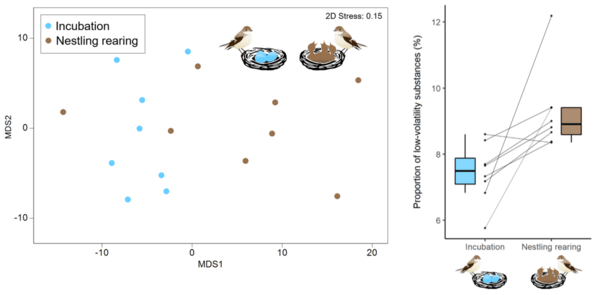

- Changes across breeding stages. Individual females could be sampled on two occasions (during incubation and nestling rearing). Interestingly, preen oil was more volatile during incubation than nestling rearing (Fig. 2). Preen oil is thus more likely to have a role in sex signalling than in olfactory crypsis in this species.

- No individual chemical signature. We found no individual signatures (very low repeatability in chemical profiles within individuals) in females that were sampled twice during the breeding season. It is therefore unlikely that Pied Flycatchers use odours for individual recognition.

Figure 2 Preen oil composition changes from incubation to nestling rearing in female Pied Flycatchers. Left: Change in overall preen oil composition between breeding stages (two-dimensional metric multidimensional scaling representing Bray-Curtis dissimilarities). Right: Preen oil contains less low-volatility substances (thus more volatile) during incubation than nestling rearing.

Can flycatchers smell this information?

We found socially-relevant information in the preen oil of flycatchers. Of course, some of the patterns observed do not necessarily imply a signalling function. Indeed, they could be the mere result of proximate causes (e.g., differences in hormones) and may also be explained by a role of preen oil in chemical protection against bacteria or ectoparasites. Still, this study provides a first step to investigate whether Pied Flycatchers use odours to communicate. Future studies should test whether these chemical differences are perceived and used by flycatchers (as was shown in other bird species, like Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis) and Estrildid Finches (Estrildidae spp.).

References

Grieves, L.A., Gilles, M., Cuthill, I.C., Székely, T., MacDougall‐Shackleton, E.A. & Caspers, B.A. 2022. Olfactory camouflage and communication in birds. Biological Reviews 97:1193-1209. VIEW

Krause, E.T., Paul, M., Krüger, O. & Caspers, B.A. 2023. Olfactory sex preferences in six Estrildid Finch species. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11. VIEW

Whittaker, D.J., Richmond, K.M., Miller, A.K., Kiley, R., Bergeon Burns, C., Atwell, J.W., & Ketterson, E.D. 2011. Intraspecific preen oil odor preferences in dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Behavioral Ecology 22:1256-1263. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: A pair of Pied Flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca) © Jörg Asmus.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.