LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Falcon fuel: metabarcoding reveals songbird prey species in the diet of juvenile Merlins (Falco columbarius) migrating along the Pacific Coast of western North America) using autonomous recording units and ecoacoustic indices. Bourbour, R. P., Aylward, C. M., Tyson, C. W., Martinico, B. L., Goodbla, A. M., Ely, T. E., Fish, A. M., Hull, A. C. & Hull, J. M. 2021. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12963. VIEW

What do raptors eat during migration? They could feed on the local wildlife that they encounter along the way. Or they might snack on migratory prey species that are travelling alongside them. The latter situation – known as the ‘migratory food web hypothesis’ – is supported by correlations between movement activity of migratory raptors and their potential prey along the migration route (Aborn 1994). However, correlation does not mean causation. Direct evidence is currently missing. To fill this knowledge gap, a group of American ornithologists took advantage of recent developments in DNA techniques (Pompanon et al. 2012). They tried to obtain DNA from prey remains on the beaks and talons of migratory Merlins (Falco columbarius) and reconstruct the diet of these birds.

Prey DNA

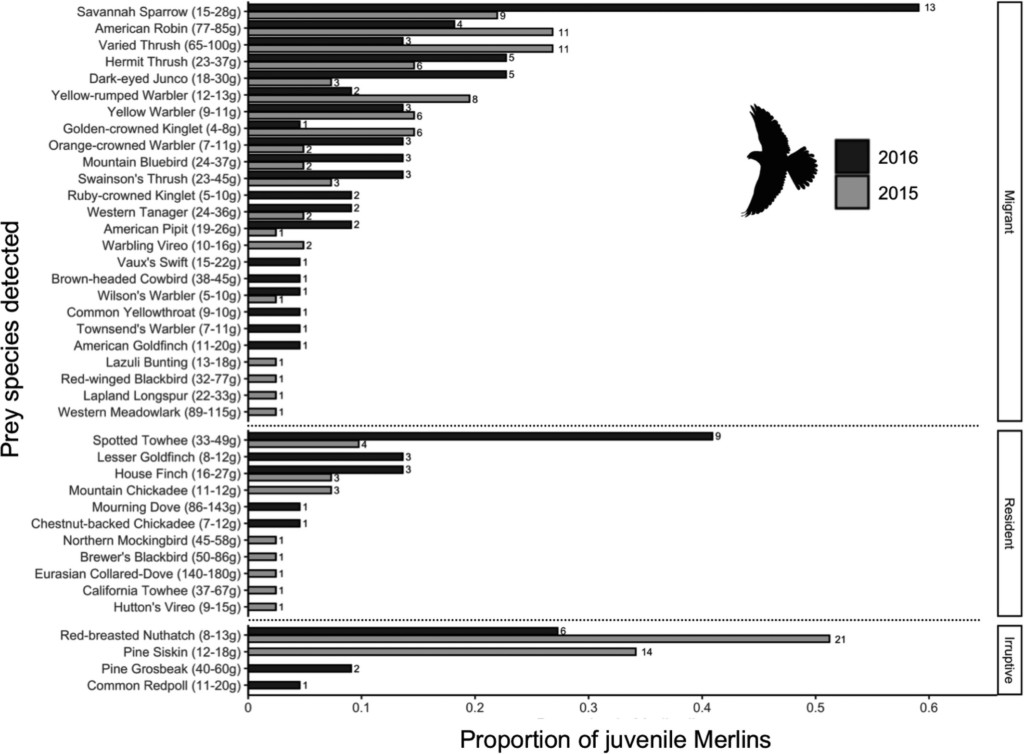

The researchers focused on Merlins that travel along the Pacific Coast of western North America. During the autumn migration of 2015 and 2016, they sampled 72 Merlins by trapping them with lure animals, such as Rock Doves (Columbia livia), European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) and House Sparrows (Passer domesticus). The prey DNA left on the beaks and talons of these falcons revealed a varied diet, with no less than 40 different prey species (excluding the lure animals). The most commonly encountered prey species were Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis), Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus) and Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus). Interestingly, the majority of these prey were migratory (29 species). These findings provide direct evidence for the ‘migratory food web hypothesis’.

Figure 1. An overview of the prey species detected from DNA on the beaks and talons of migratory Merlins in 2015 (grey) and 2016 (black). The prey species are divided into regular migrants, residents and irruptive migrants.

Raptor conservation

Migratory songbirds are thus falcon fuel (as the authors nicely put it in the title of their paper) for the costly long-distance migration of Merlins. This insight is not only an interesting bird fact, it can also inform conservation efforts. Raptors are extremely vulnerable for environmental toxins, such as lead or mercury, that can accumulate in their diet (Chandler et al. 2004). A detailed picture of the prey items that raptors consume during their annual cycle can help conservationists to pinpoint vulnerable life stages and take appropriate measures (Marra et al. 2015). Good that Merlins are such messy eaters that don’t wipe their beaks.

References

Aborn, D.A. (1994). Correlation between raptor and songbird numbers at a migratory stopover site. The Wilson Bulletin 106: 150– 154. VIEW

Chandler, R.B., Strong, A.M. & Kaufman, C.C. (2004). Elevated lead levels in urban House Sparrows: a threat to Sharp-shinned Hawks and Merlins? Journal of Raptor Research 38: 62– 68. VIEW

Marra, P.P., Cohen, E.B., Loss, S.R., Rutter, J.E. & Tonra, C.M. (2015). A call for full annual cycle research in animal ecology. Biology Letters 11: 20150552. VIEW

Pompanon, F., Deagle, B.E., Symondson, W.O., Brown, D.S., Jarman, S.N. & Taberlet, P. (2012). Who is eating what: diet assessment using next generation sequencing. Molecular Ecology 21: 1931– 1950. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Merlin (Falco columbarius) | David St. Louis | CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here