LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Historical avifaunal change and current effects of hiking and road use on avian occupancy in a high-latitude tundra ecosystem. Meeker, A., Marzluff, J. & Gardner, B. 2021 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13034 VIEW

In Denali National Park (hereafter Denali), nearby residents have long been in tune with the landscape and wildlife that surrounds them. In recent years, many locals have noticed a decreasing presence in both the abundance and diversity of birds. This has correlated with increased tourism and relaxed park management. The degradation of the once teeming wilderness is alarming to many residents and they would like to see more effort being placed on the preservation and conservation of wildlife within the park.

Denali has a long and unique history of being a trail-less wilderness full of wildlife. Unlike many other National Parks, it remains largely natural, there are few maintained trails and only one road in and out of the park’s boundary. Recently, changes have been made to build more trails and increase the number of places for people to congregate and disperse on the landscape. This increased human presence is adding to locals’ worries that further degradation of the landscape and environment will continue reducing the presence of local wildlife. These changes are being fuelled by questionable management decisions, an expanding cruise ship industry, and a suite of backcountry lodges being run with the sole goal of increasing day-use visitor numbers.

The current state of Denali is nothing like what it used to be just decades ago. Through our recent interviews and reviewing a long-documented history from naturalists such as Charles Sheldon, Joseph Dixon and Adolf Murrie, we have been able to paint a picture of what Denali was like before the recent eruption of human-centric changes. In comparing these historical accounts with the current state of bird populations in Denali, we learned that many species are currently struggling, and some iconic tundra species including the American Golden Plover (Pluvialis dominica), Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea), Northern Wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe), and Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) have almost entirely disappeared from the park road corridor (Murie 1946, McIntyre 2017). While this high latitude tundra ecosystem faces a multitude of pressures, the presence of humans on the landscape is one of the most pronounced and measurable changes.

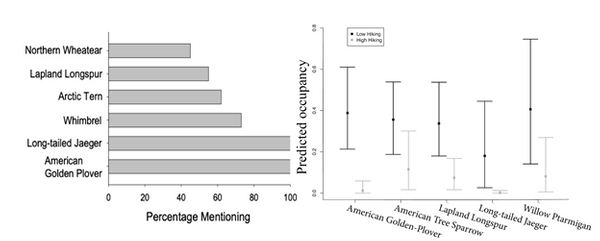

To gain an understanding of the impact of humans on Denali’s wildlife, I worked with Dr. John Marzluff at the University of Washington. We used a two-pronged approach to understand how the ecological baseline of the park has slowly shifted over the past 40 years and to measure the current occupancy trends of birds on the tundra (Soga and Gaston 2018). We interviewed eleven long-term park residents who all noted multiple species they believed to be in decline or extinct from historical areas. We extensively surveyed the tundra for most of these species mentioned using line transects. In our analysis we used a spatial occupancy model, taking into account nine occupancy and eight detection variables. We found that human-caused disturbances from the road and hiking led to declines for five tundra species. From the interview information and based on our surveys we now understand four bird species are practically extinct from the park road corridor: the American Golden Plover, Arctic Tern, Northern Wheatear and Whimbrel. Furthermore, in reviewing historical texts by Charles Sheldon and Adolf Murrie written in the early 1900s, we learned that there used to be a dramatically more abundant and diverse collection of birds in the park than we see today (McIntyre 2017).

Figure 1 Interview responses to species declining within Denali National Park. (Right) Predicted occupancy probabilities in low and high hiking areas.

As we analysed our recently collected data we concluded that the park road and disturbance from hiking were important factors for species occupancy. The road is the most constant source of human disruption on the landscape and in the tundra, where noise and movement can be detected from far distances because of the absence of tall vegetation. We found that the road is currently having a mixed effect, attracting a few species who may exploit its edge, while others avoid the disturbance entirely. In regards to hiking, tundra-nesting birds of conservation concern occupied areas with moderate to high rates of hiking less frequently than they occupied sites with little to no hiking. We suggest that park managers seeking to balance human recreation with the needs of sensitive tundra-breeding birds should regulate hiking, especially during breeding months.

Reimplementing vehicle limits combined with hiking regulations could potentially create the proper conditions for wildlife to begin to rebound and eventually thrive again in Denali. For the average hiker, we recommend reducing your hiking in the early breeding season (May through June) especially in the tundra. Locals who originally sounded the alarm on species loss are looking for some sort of management solution concerning human access. “Reducing buses”, “less trail building”, “celebrating the wilderness culture” and “tundra education” were all suggested as park strategies that could help return Denali to a park where all wild animals thrive.

References

McIntyre, C. 2007. Apparent changes in abundance and distribution of birds in Denali National Park. Alaska Park Science 7: 62-65. VIEW

Murie, A. 1946. Observations on the Birds of Mount McKinley National Park, Alaska. Condor 48: 253-261. VIEW

Soga, M. & Gaston, K.J. 2018. Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 16: 222-230. VIEW

Vrezec, A. & Tome, D. 2004b. Altitudinal segregation between Ural Owl Strix uralensis and Tawny Owl S. aluco: evidence for competitive exclusion in raptorial birds. Bird Study 51: 264-269. VIEW

Zárybnická, M., Sedláček, O., Salo, P., Šťastný, K. & Korpimäki, E. 2015. Reproductive responses of temperate and boreal Tengmalm’s Owl Aegolius funereus populations to spatial and temporal variation in prey availability. Ibis 157: 369-383. VIEW

Top right: American Golden Plover Pluvialis dominica © Avery Meeker.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.