LINKED PAPER

Breeding great tit Parus major individuals have moderately consistent foraging niches across years. Olivé-Muñiz, M., Pagani-Núñez, E. & Senar, J.C. 2021 Ardeola. doi: 10.13157/arla.68.2.2021.ra6 VIEW

Great Tits (Parus major) are usually conceived as a generalist species because a population can consume a wide variety of different prey (they are especially fond of caterpillars and spiders but they will hunt down other arthropods provided the chance). However, if you focus your attention on an individual level, you can see differences arise in prey selection between individuals. This is commonly known as individual specialisation. But why is that worthy of consideration? If individuals specialise in a long-term basis on a limited number of prey types, they can be under different selective pressures. Therefore, they can be affected by changes in the environment, which can have important ecological, evolutionary and conservation implications. For example, it can affect intraspecific competition levels and the capacity of the population to diversify and perhaps speciate (Bolnick et al., 2002; Araújo et al., 2011).

Figure 1 Female Great Tit Parus major incubating inside one of the nest-boxes of the study area © Marta Olivé Muñiz.

However, apart from demonstrating that different individuals of the same population make different prey choices, a key step towards proving true individual specialisation is to determine whether the foraging niche of an individual is consistent in the long term. That means to analyse if said specialisation is maintained over the years despite the different conditions that individuals encounter during different breeding seasons. Some studies have found evidence of consistency of the foraging niche of adult individuals in different vertebrate species (Schindler et al., 1997; Vander Zanden et al., 2010; Ceia et al., 2012). However, the consistency of the parental provisioning behaviour is a highly overlooked topic despite being critical on the reproductive success of the adults.

Figure 2 Images extracted from the nest box recordings showing a male bringing a caterpillar (left) and a female bringing a spider (right) © Marta Olivé Muñiz.

We analysed the consistency of the diet provided to offspring in a Mediterranean Great Tit population which presents appropriate conditions for this kind of study, i.e. individuals showing dietary specialisation which is also consistent within the breeding season (Pagani-Núñez et al., 2015). To do so, during the breeding season we put cameras inside the nest boxes to record which type and size of prey the parents were delivering to their offspring. We gathered data obtained over six years to analyse if individuals maintained their prey choices over different years. First, we performed an absolute consistency analysis, which is based on comparing the closeness of prey selected one year to the one chosen in another year. But what if in some breeding seasons the caterpillars are less abundant due to environmental variables and specialists cannot select them as much as they would want to? Since prey availability can differ from one year to another, the results obtained could be masked if only the absolute value is taken into account. Therefore, we carried out a relative consistency measure based on analysing the consistency of the position of individuals relative to the others. In other words, to analyse if a high caterpillar consumer will always be one of the top caterpillar consumers within the population. It is important to stress that in said analyses we accounted for factors that could affect the foraging niche such as the date of recording, brood size, vegetation around the nest box and the effects of year and individuals.

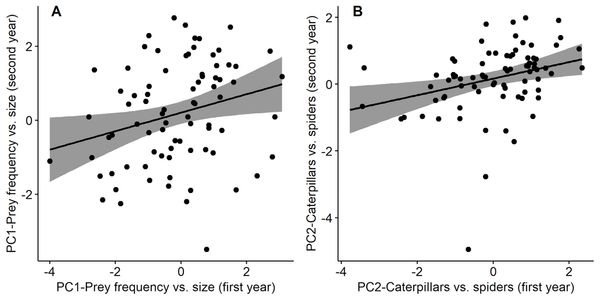

Our preliminary analysis showed that the dietary choices of the population can be represented with two axes. One called “Prey frequency vs. size”, which told us that individuals selecting bigger prey were delivering a smaller number of prey and vice versa. The other one was called “Caterpillars vs. spiders”, which showed that there were caterpillar specialists and spider specialists in the population (as well as generalist individuals in the middle of the spectrum).

Figure 3 Consistency of the relative foraging niche across years (N = 80). A) Regression between prey frequency vs. size delivered to offspring each year (year x, i.e., first year) and the one of the next year (year x + 1, i.e., second year). B) Regression between caterpillars vs. spiders delivered to offspring each year (year x, i.e., first year) and the one of the next year (year x + 1, i.e., second year). Regression lines and 95% confidence intervals are shown.

With this information we performed the absolute and relative consistency analyses, and both came to the same conclusion – breeding Great Tits have moderately significant consistent foraging niches throughout years regarding parental provisioning. In Figure 3 the results obtained with the relative analysis are displayed. Each point represents one individual and the black line represents the consistency displayed by the whole population. The steeper the slope, the higher the population’s consistency. Therefore, the results show that a spider specialist individual will, to some extent, tend to deliver to its offspring this type of prey each breeding season. This suggests that, though there seems to be a preference in prey selection, there is diet plasticity when parents have the urge to feed their chicks. This could reduce the population diet consistency and help them to deal with fluctuating environmental conditions. Alas, we still do not fully understand either how prey choice consistency varies between individuals, species and environments or how this individual specialisation is defined. Notwithstanding what we know is that, as usual, we need to do more research to untangle this matter!

References

Araújo, M.S., Bolnick, D.I. & Layman, C.A. 2011. The ecological causes of individual specialisation. Ecology Letters 14: 948-958. VIEW

Bolnick, D.I., Yang, L.H., Fordyce, J.A., Davis, J.M. & Svanbäck, R. 2002. Measuring individual-level resource specialization. Ecology 83: 2936-2941. VIEW

Ceia, F.R., Phillips, R.A., Ramos, J.A., Cherel, Y., Vieira, R.P., Richard, P. & Xavier, J.C. 2012. Short- and long-term consistency in the foraging niche of wandering albatrosses. Marine Biology 159: 1581-1591. VIEW

Pagani-Núñez, E., Valls, M. & Senar, J.C. 2015. Diet specialization in a generalist population: the case of breeding great tits Parus major in the Mediterranean area Oecologia 179: 629-640. VIEW

Schindler, D.E., Hodgson, J.R. & Kitchell, J.F. 1997. Density-dependent changes in individual foraging specialization of largemouth bass Oecologia 110: 592-600. VIEW

Vander Zanden, H.B., Bjorndal, K.A., Reich, K.J. & Bolten, A.B. 2010. Individual specialists in a generalist population: results from a long-term stable isotope series Biology Letters 6: 711-714. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Great Tit Parus major © Marta Olivé Muñiz.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.