LINKED PAPER

Food availability limits avian reproduction in the city: An experimental study on great tits Parus major. Seress, G., Sándor, K., Evans K. L. & Liker, A. 2020. Journal of Animal Ecology. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2656.13211. VIEW

Urbanization, converting natural habitats into towns and cities, has become one of the most important global causes of species’ population declines and habitat loss (Seto et al. 2012). Deliberately or not, in our built-up environment we alter virtually all the key environmental and ecological factors which, in turn, profoundly affect species composition and populations’ persistence in urban animal communities. While some of these human-induced changes, like the milder climate or anthropogenic food supply during winters could be beneficial, most of the factors associated with our cities and towns are detrimental for wildlife (Seress & Liker 2015).

In urban avian ecology, one of the most documented ‘symptoms’ of urbanization is that many insectivorous birds reach generally lower breeding success and nestling development in their urban compared to rural populations – the Great Tit Parus major provides an ideal example of this.

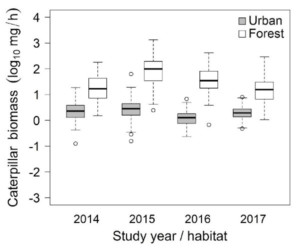

Previous works suggest that one of the main ‘culprits’ for this phenomenon could be ‘food limitation’, that is urban environments do not provide sufficient amounts of high-quality food during birds’ breeding season. Indeed, we showed earlier (Seress et al. 2018) that mature trees at our urban study areas in Hungary – similarly to many other urban environments – harbour dramatically lower biomass of caterpillars, the difference being up to 20-fold in some years between the cities and forests (Fig. 1). These larvae are key components of the optimal offspring diet in many songbirds, as they contain almost everything that is needed for fast-growing nestlings, like proteins, vitamins, essential fatty acids, and carotenoids. In parallel with this, we also found that urban great tit nestlings suffer from more frequent nestling mortality, presumably from starvation. However, the direct link between these patterns has not been inferred experimentally until now.

Figure 1 Differences in caterpillar biomass between the urban (gray) and forest (white) study sites in 2014-2017 (year of the study: 2017). Caterpillar biomass was estimated from frass samples collected throughout the birds’ brood-rearing period. Note that values were log-transformed

To take up this challenge and test if food limitation in urban environments is indeed responsible for birds’ reduced reproductive success we manipulated urban and forest nestlings’ diet in a field experiment. Urban nest-boxes were placed in public parks, university campuses, and cemeteries within the city of Veszprém, while the forest study site was an oak-dominated woodland c. 3 km from the city.

During the chick-rearing period, broods either received nutritionally enhanced mealworms daily (to meet 40-50% of each brood’s food requirements) or received no extra food (controls). Next, to measure the impacts of extra food in both habitat types, we assessed chicks’ survival rates in the nest and their body size just before they fledged. We also wanted to know if parents indeed used the supplementary food in both urban and forest areas, so we mounted small, hidden cameras on the nest boxes. These provisioning videos revealed that parents readily utilized the ‘free meal’ and fed most of the mealworms to their chicks in both habitats, and that control pairs did not steal mealworms from the supplementary fed pairs (Fig 2).

Figure 2 A pair of supplemented urban Great Tits feasting on the provided mealworms. Supplemented parents readily fed their chicks with the extra food in both habitats @ Gábor Seress

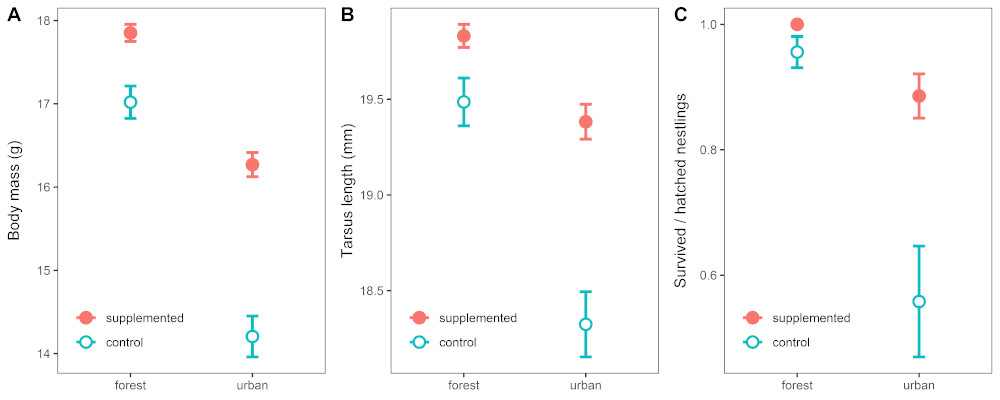

Our results clearly indicate that the high-quality arthropod food greatly enhanced the breeding success of urban great tits: supplemented urban nestlings’ survival probability reached 0.88 while this was only 0.58 in urban control broods. Further, pairs with access to the extra insect-rich nestling food raised significantly heavier and bigger fledglings. This benefit was especially striking in fledglings’ body mass: urban supplemented nestlings weighed an average 2g more, an increase of 15% when compared to the body mass of urban chicks that did not gain extra food. This is a substantial difference. Evidence from other studies in natural areas (Naef-Daenzer et al. 2001) suggests that this greater body mass when leaving the nest may increase these chicks’ chance of surviving to spring and breeding themselves. Very importantly, such beneficial effects of supplementary food were not apparent in the forest site where natural nestling food is abundant (Fig 3).

Figure 3 Differences (mean ± SE) in 15 days old Great Tit nestlings’ (A) body mass, (B) tarsus length, and (C) nestling survival in the groups of different habitat × treatment combinations. Click to view larger

Figure 3 Differences (mean ± SE) in 15 days old Great Tit nestlings’ (A) body mass, (B) tarsus length, and (C) nestling survival in the groups of different habitat × treatment combinations. Click to view larger

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that urban supplemented nestlings pretty much closed up the differences in body size and survival rates compared to those in forest control nests. This result indicates that the insect-rich diet alone could largely mitigate the well-known, marked differences in nestling size and survival rates between urban and forest birds. It thus strongly indicates that in our case urban stressors other than food shortages probably contributed relatively little to urban birds’ reduced breeding success. Their indirect effects on urban insect populations, hence on birds’ food supply, might though still be substantial.

Finally, these results also enable us to broadly assess the magnitude of food limitation in our urban study system. Given the positive impacts of the amount of extra food and considering that urban great tit clutches are c. 25% smaller than those in forests (Seress et al. 2018), we assume that urban caterpillar populations in our study system would need to be increased by a factor of at least 2.5 for urban birds to reach similar reproductive success to their forest conspecifics. However, probably much higher increases are needed given that other urban passerine species also depend on caterpillars to raise their offspring and will thus compete with great tits for this food supply.

Mitigating the adverse effects of urbanization on arthropod faunas, thereby enhancing habitat quality for urban insectivorous birds will probably require numerous changes in urban green space management practices. Research is urgently needed to assess how to bolster urban insect populations effectively and using methods that would be welcomed, or at least tolerated, by local residents.

References

Seto, K. C., Güneralp, B., & Hutyra, L. R. 2012. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109: 16083-16088. VIEW

Seress, G., & Liker, A. 2015. Habitat urbanization and its effects on birds. Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 61: 373-408. VIEW

Seress, G., Hammer, T., Bókony, V., Vincze, E., Preiszner, B., Pipoly, I., Sinkovics, C., Evans, K.L. & Liker, A. 2018. Impact of urbanization on abundance and phenology of caterpillars and consequences for breeding in an insectivorous bird. Ecological Applications, 28: 1143-1156. VIEW

Naef‐Daenzer, B., Widmer, F., & Nuber, M. 2001. Differential post‐fledging survival of great and coal tits in relation to their condition and fledging date. Journal of Animal Ecology, 70: 730-738. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: A male urban Great Tit Parus major bringing the supplemented mealworms for his chicks © Gábor Seress