LINKED PAPER

Survival rates of wild and released White-rumped Vultures (Gyps bengalensis), and their implications for conservation of vultures in Nepal. Mallord, J., Bhusal, K., Joshi, A., Karki, B., Chaudhary, I., Chapagain, D., Thakuri, D., Rana, D., Galligan, T., Requena, S., Bowden, C., Green, R. 2024. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13303 VIEW

At the height of the Asian vulture crisis, which began in the mid-1990s, in India vultures were suffering 40-50% annual mortality and came close to extinction (Prakash et al. 2012), with the worst-hit species, White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis declining by a staggering 99.9% during this period (Prakash et al. 2007). This was all down to unintentional poisoning by the veterinary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) diclofenac. The result was the banning of this drug across south Asia, the identification of another NSAID that was safe to vultures (meloxicam) and the establishment of conservation breeding centres as an insurance policy in case the worst-case scenario materialised, and vultures went extinct in the wild.

Fast forward almost two decades and vulture populations in some countries have either stabilised (albeit at a far reduced level) or even started to recover. The latter is true of Nepal, where populations have increased rapidly since 2013, coincident with the onset of nationwide conservation advocacy (Galligan et al. 2020). Data from undercover pharmacy surveys (Galligan et al. 2021) has showed that availability of diclofenac has been reduced to zero, especially in areas where most vultures are found. As a result, in 2017 a decision was made to release White-rumped Vultures that were being held in the captive breeding population.

Figure 1. Wild adult ‘E0’. Although spending most of its time at the Jatayu Restaurant, E0 unexpectedly travelled 800 km south to Maharashtra in India, before almost immediately returning to Nepal © Ankit B. Joshi, BCN.

A recently published paper in the journal Ibis (Mallord et al. 2024) uses the data obtained from GPS-tagged birds to estimate and compare annual survival rates and home range sizes of wild and released White-rumped Vultures. Wild birds were trapped at the Jatayu Vulture Restaurant in the village of Pithauli on the edge of Chitwan National Park, with the use of walk-in traps baited with NSAID-free cattle or buffalo. Captive birds were moved to an aviary at the restaurant, and later tagged a week before release. Between 2017 and 2022, a total of 50 wild birds have been tagged along with 49 birds that were released from the breeding programme.

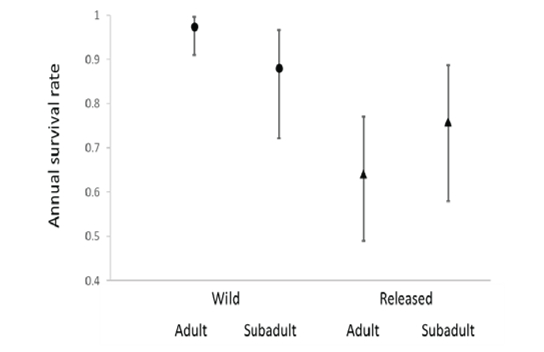

So, what did the results show? Firstly, wild birds have very high annual survival rates, 97% for adults and 88% for immatures. These rates compare favourably with survival estimates of Gyps vulture populations from elsewhere in the world that are not impacted by high levels of anthropogenic mortality. This confirms that the threat from diclofenac has disappeared from Nepal, as well as suggesting that other potential risks – such as the use of poison baits or electrocution – are also operating at a low enough level not to impact vulture survival, and of course population trends.

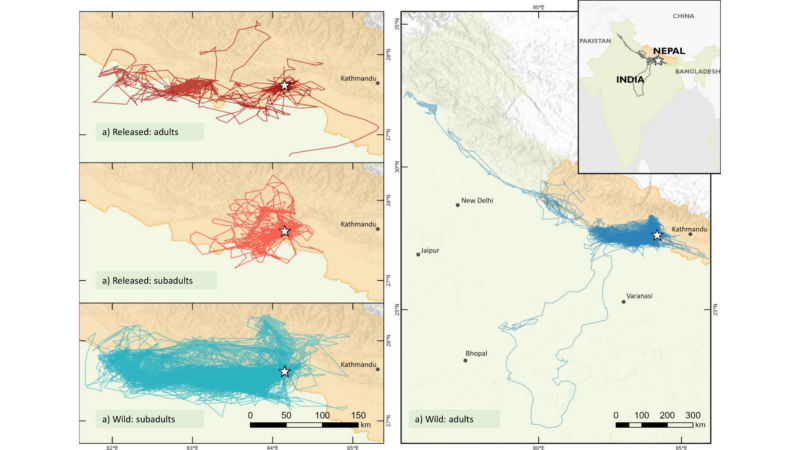

A key aspiration of any reintroduction programme is that released birds survive and behave the same as their wild counterparts. However, this hasn’t been the case for the released White-rumped Vultures. Their movements have been confined to a far smaller area, being more reliant on food provided at the Jatayu Restaurant. Hence, wild birds’ home ranges have been 1-2 orders of magnitude larger.

Figure 2. A summary of the movements of wild (blue) and released captive (red) GPS-tagged White-rumped Vultures. Tagging location / release site indicated by star.

Not only that, but estimates of annual survival have been lower, too: 64% and 76% for adults and immatures, respectively. The particularly low rate for adults is especially concerning, but perhaps isn’t that surprising. They were the birds that had originally been taken into captivity as chicks and captive-reared and had spent up to a decade in captivity before release. This is likely to have had a detrimental effect on the birds’ flight capability, ability to find food and naivety when faced with new stimuli, e.g., potential predators and humans. However, the probability of survival increased the longer birds spent in the wild, suggesting they were becoming better adapted to their new surroundings. Another positive sign is that some of the released birds have already started to breed successfully. It is hoped that their offspring will behave, and survive, like other wild vultures.

Figure 3. Annual survival rates of wild and released GPS-tagged White-rumped Vultures.

One of the key advantages of monitoring birds fitted with telemetry devices is the ability to find birds once they have died, enabling you send them for post-mortem analysis, whereby you can get an unbiased view of the importance of different causes of death. Interestingly, the main issue for the tagged vultures, especially those released from captivity, was being found in a weakened condition from dehydration and starvation. This highlights the importance of continuing to feed the vultures long after they are released.

But perhaps the most important finding was that there was no evidence that poisoning by diclofenac – or any other NSAID – caused the death of any of the tagged vultures. As a result of this, along with the removal of diclofenac from pharmacies, and of course the rapidly increasing populations of vultures, the area where the tagged birds ranged was declared as the world’s first genuinely safe Vulture Safe Zone (SAVE 2021).

References

Galligan, T.H., Bhusal, K.P., Paudel, K., Chapagain, D., Joshi, A.B., Chaudhary, I.P., Chaudhary, A., Baral, H.S., Cuthbert, R.J., Green, R.E. 2020. Partial recovery of Critically Endangered Gyps vulture populations in Nepal. Bird Conservation International 30:1. VIEW

Galligan, T.H., Mallord, J.W., Prakash, V.M., Bhusal, K.P., Alam, A.B.M.S., Anthony, F.M., Dave, R., Dube, A., Shastri, K., Kumar, Y., Prakash, N., Ranade, S., Shringarpure, R., Chapagain, D., Chaudhary, I.P., Joshi, A.K., Paudel, K., Kabir, T., Ahmed, S., Azmiri, K.Z., Cuthbert, R.J., Bowden, C.G.R., Green, R.E. 2021. Trends in the availability of the vulture-toxic drug, diclofenac, and other NSAIDs in South Asia, as revealed by covert pharmacy surveys. Bird Conservation International 31:3. VIEW

Prakash, V., Bishwakarma, M.C., Chaudhary, A., Cuthbert, R., Dave, R., Kulkarni, M., Kumar, S., Paudel, K., Ranade, S., Shringarpure, R., Green, R.E. 2012. The population decline of Gyps vultures in India and Nepal has slowed since veterinary use of diclofenac was banned. PLoS ONE 7:11. VIEW

Prakash, V., Green, R.E., Pain, D.J., Ranade, S.P., Saravanan, S., Prakash, N., Venkitachalam, R., Cuthbert, R., Rahmani, A.R., Cunningham, A.A. 2007. Recent changes in populations of resident Gyps vultures in India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 104:2. VIEW

SAVE. 2021. First ever Vulture Safe Zone declared fully safe in Nepal at SAVE’s 11th Annual Meeting. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Mixed group of vultures at the Jatayu Restaurant © John Mallord.

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.