Report from a BOU-funded project

LINKED PAPER

High temperatures drive offspring mortality in a cooperatively breeding bird. Bourne, A.R., Cunningham, S.J., Spottiswoode, C. & Ridley, A.R. 2021 Proceedings of the Royal Society B. DOI: 10.1098/rspb2020.1140 VIEW

Birds use a variety of different cues to decide when to start breeding. Changes in the type and abundance of resources, like food or water, can influence both the timing of breeding and breeding outcomes. Timing breeding to coincide with resource pulses in the local environment is crucial in order to both produce and successfully raise young. When resources are limited, reproductive success declines and some bird species will even forgo breeding entirely. Because rainfall in sub-tropical environments is often associated with resource pulses, like grass growth or invertebrate emergence, it is often assumed that birds living in arid areas will wait until after it has rained before they start breeding. However, resource pulses can also be associated with patterns of plant productivity responding to other kinds of environmental cues, such as changes in temperature or day length.

Birds use a variety of different cues to decide when to start breeding. Changes in the type and abundance of resources, like food or water, can influence both the timing of breeding and breeding outcomes. Timing breeding to coincide with resource pulses in the local environment is crucial in order to both produce and successfully raise young. When resources are limited, reproductive success declines and some bird species will even forgo breeding entirely. Because rainfall in sub-tropical environments is often associated with resource pulses, like grass growth or invertebrate emergence, it is often assumed that birds living in arid areas will wait until after it has rained before they start breeding. However, resource pulses can also be associated with patterns of plant productivity responding to other kinds of environmental cues, such as changes in temperature or day length.

Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor (hereafter ‘pied babblers’) are cooperatively-breeding, group-living, territorial birds endemic to the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa. A team of us, led by Prof. Amanda Ridley, have been studying a habituated population of these birds for more than 15 years. One of the things that intrigues us about their behaviour is that they start breeding predictably in September or October every year, at the end of the cold, dry winter and usually well before any substantial summer rain. Pied babblers will continue to breed throughout the austral summer if there has been substantial rainfall in December or January, but will generally stop breeding by December if there hasn’t been much rain. It seemed to us that rain would extend the breeding season but was actually not required to initiate it. What, then, is the cue that they are responding to?

Pied babblers are ground foragers, searching for invertebrate prey under trees and shrubs. They make a good model for understanding the relationship between diet, seasonal weather fluctuations and reproduction because they are endemic to an area that experiences periodic drought and do not move to relieve the effects of such droughts. Our previous research means that their reproductive ecology is well understood. We wanted to know whether pied babblers used different food sources early in the breeding season (September – October, when breeding begins) compared to later (November – March, when it usually rains), as this might explain why they are able to breed before rain. We then used stable isotope analyses to test whether any seasonal dietary shifts we observed in the birds’ foraging behaviour would also be detectable in the carbon and nitrogen signatures of their droppings. Being able to detect dietary shifts in the droppings could reduce the need for lengthy and expensive fieldwork involving detailed behaviour observations.

Figure 1 A fresh Southern Pied Babbler Turdoides bicolor dropping (Photo by A. Bourne).

Figure 1 A fresh Southern Pied Babbler Turdoides bicolor dropping (Photo by A. Bourne).

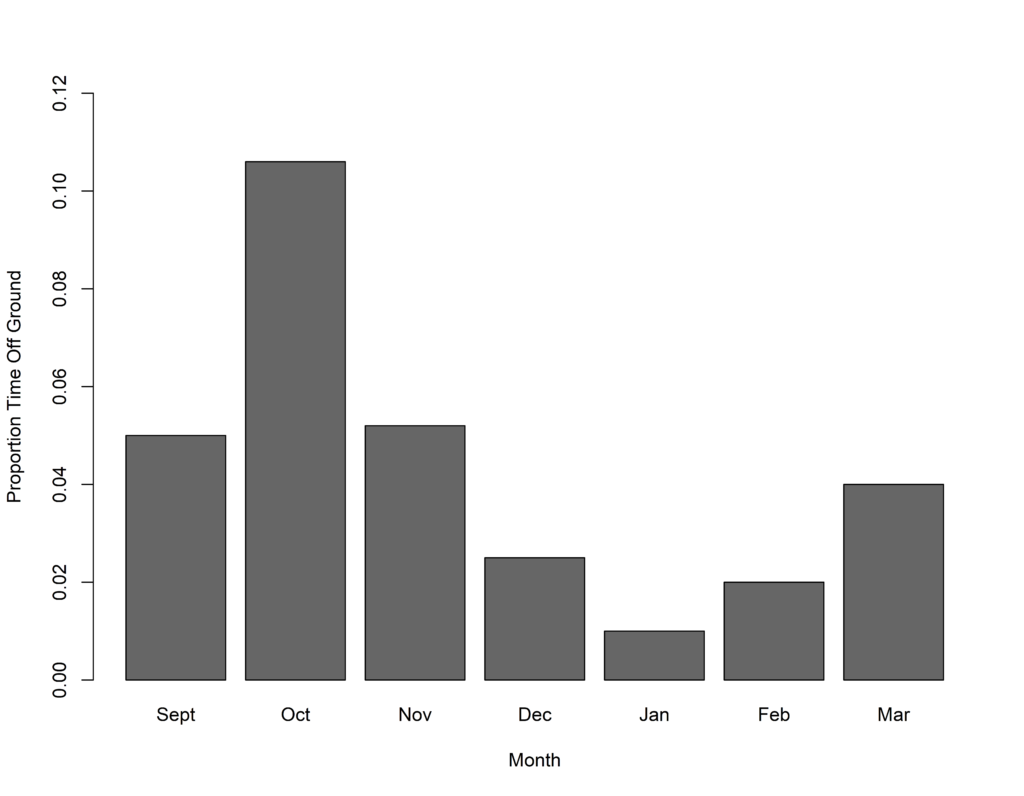

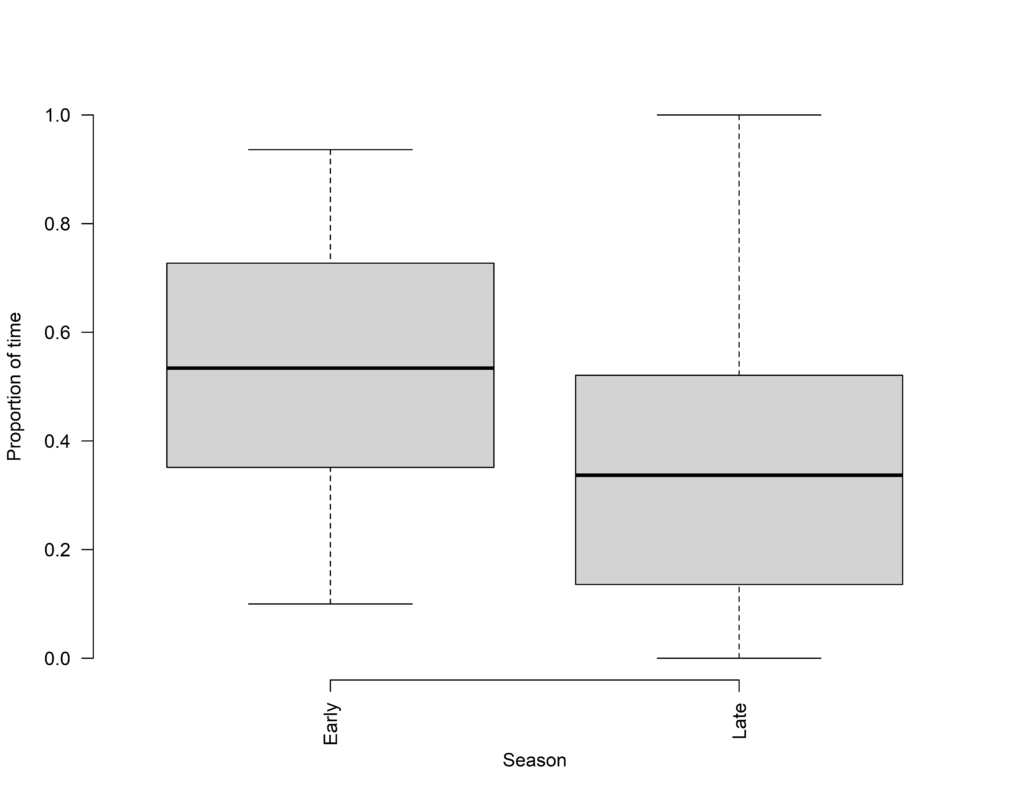

We found, as we expected, that pied babblers foraged mostly on the ground throughout the summer. However, the proportion of time they spent foraging off the ground, gleaning insects out of trees, was significantly higher earlier in the breeding season compared to later. Pied babblers also preferred particular trees as foraging spots throughout the summer, specifically Camelthorn Vachellia erioloba and Blackthorn Senegalia mellifera trees, using other plants in keeping with their availability in the environment and avoiding bare, open ground. However, the proportion of time spent foraging in or under Camelthorn trees was significantly higher earlier in the breeding season compared to later. Our behavioural observations strongly suggest the presence of an arboreal food source, associated with Camelthorn trees and available early in the breeding season, which is not available later. Furthermore, this food source is independent of rainfall, as it is present before the peak in summer rain. It is likely related to the phenology of Camelthorn trees.

Figure 2 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor were much more likely to be observed foraging off the ground early in the breeding season compared to later in the breeding season. Arboreal foraging is a relatively unusual behaviour in this species.

Figure 2 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor were much more likely to be observed foraging off the ground early in the breeding season compared to later in the breeding season. Arboreal foraging is a relatively unusual behaviour in this species.

Figure 3 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor were more likely to be observed foraging in Camelthorn trees early in the breeding season compared to later in the breeding season.

Figure 3 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor were more likely to be observed foraging in Camelthorn trees early in the breeding season compared to later in the breeding season.

Camelthorn trees, a keystone species in the Kalahari, flower and produce pods during August and September, responding predictably each year to a combination of temperature and day length cues. They are extremely deep-rooted, and access ground water to the extent that, once established, they are impervious to all but the most extreme droughts. Seasonal leaf and fruit growth is an important source of food for caterpillars, which the pied babblers then use to feed themselves and their young. It therefore seems highly likely that the onset of breeding in pied babblers is timed to take advantage of this relatively predictable, and substantial, seasonal food resource cue.

Figure 4 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor are endemic to the Kalahari Desert, an arid savannah system in southern Africa. Camelthorn trees Vachellia erioloba are a keystone species in this environment.

Figure 4 Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor are endemic to the Kalahari Desert, an arid savannah system in southern Africa. Camelthorn trees Vachellia erioloba are a keystone species in this environment.

We did not find any significant differences between the carbon and nitrogen isotope signatures in the droppings that we collected earlier and later in the season. While we clearly saw large differences in foraging behaviour, a negligible difference in isotopic signatures suggests that the insects eaten by pied babblers largely consumed food from tree and shrub food sources throughout the breeding season. We would only have been able to detect a dietary shift using stable isotope analysis if the invertebrate prey had been feeding primarily on tree and shrub derived foods earlier in the season, before rain, and grass-derived foods later in the season, after rain.

Our observations of foraging behaviour suggest that pied babblers consume caterpillars feeding on Camelthorn trees earlier in the breeding season, and this resource pulse stimulates the onset of breeding. It therefore appears that this arid-zone species uses insect prey availability, and not rainfall, as a cue to initiate breeding. Given the extremely important relationship between pied babblers and Camelthorn trees, efforts to conserve and manage this endemic bird species should also include efforts to conserve and manage the iconic Camelthorn.

The project received a research grant from the BOU in 2020 for which the project team is extremely grateful. The author wishes to thank her supervisors Dr Susan Cunningham and Associate Professor Amanda Ridley, colleagues Dr Grant Hall and Professor Andrew McKechnie and University of Pretoria Honours student Liame Marais for their important contributions to this study. Camilla Soravia and Lesedi Moagi assisted with fieldwork. This research received additional funding from the National Research Foundation, South Africa, the Universities of Pretoria and Cape Town, and the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology.

Funding

Amanda Bourne (PhD candidate, Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, South Africa) was awarded a small ornithological grant of £1,440 in 2020 for a project entitled ‘Do seasonal changes in food resources predict breeding phenology and reproductive success in Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor?’.

References

Dean, W.R.J., Milton, S.J. & Jeltsch, F. 1999. Large trees, fertile islands, and birds in arid savanna. Journal of Arid Environments 41: 61–78. VIEW

Krug, J.H.A. 2017. Tree water potentials supporting an explanation for the occurrence of Vachellia erioloba in the Namib Desert (Namibia). Forest Ecosystems 4: 20. VIEW

Ridley, A.R. 2016. Southern pied babblers: The dynamics of conflict and cooperation in a group-living society. In Dickinson J.L. & Koenig W. (Eds.) Cooperative Breeding in Vertebrates: Studies of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior. (pp. 115–132) Cambridge University Press.

Ridley, A.R., Wiley, E.M., Bourne, A.R., Cunningham, S.J. & Nelson-Flower, M.J. 2021. Understanding the potential impact of climate change on the behavior and demography of social species: The pied babbler (Turdoides bicolor) as a case study. Advances in the Study of Behavior 53: 225–266. VIEW

Wolf, B.O. & Martínez del Rio, C. 2003. How important are columnar cacti as sources of water and nutrients for desert consumers? A review. Isotopes in Environmental and Health Studies 39: 53–67. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Southern Pied Babblers Turdoides bicolor Credit: Nicholas B. Pattinson