LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Hidden effects of high numbers of tourists in protected areas: displacement of foraging top scavengers. Donázar, J.A., Cortés-Avizanda, A., Arrondo, E., Delgado-González, A., Ceballos, O. 2022 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13121 VIEW

Since the mid-twentieth century, and increasingly in recent decades, the birth of the “leisure era” has led to the use by society of natural spaces for primarily recreational purposes (Buckley 1991). Today, uses of natural areas may have an ecotourism orientation, based on the observation and enjoyment of natural values such as wildlife (Penteriani et al. 2017, Cortés-Avizanda et al. 2021), outdoor sports (Malchrowicz-Mośko et al. 2019), as well as uses linked to cultural and religious practices (Dudley et al. 2009). However, this growing human use of protected areas could have severe ecological costs (Buckley 1991, Belsoy et al. 2012).

Therefore, research on the consequences of tourism in general and ecotourism in particular on natural systems is increasingly needed to support accurate resource management. Focusing on wildlife, knowledge of the effects of human disturbance has risen steeply in recent decades. In particular, raptors are exposed to the so-called “weekend effect” by which individuals avoid areas with higher road traffic and human presence, increasing the size of their home ranges (see Bautista et al. 2004, Perona et al. 2019, and references therein).

Figure 1 Vulture flying at Bardenas Reales Natural Park: © Sergio González

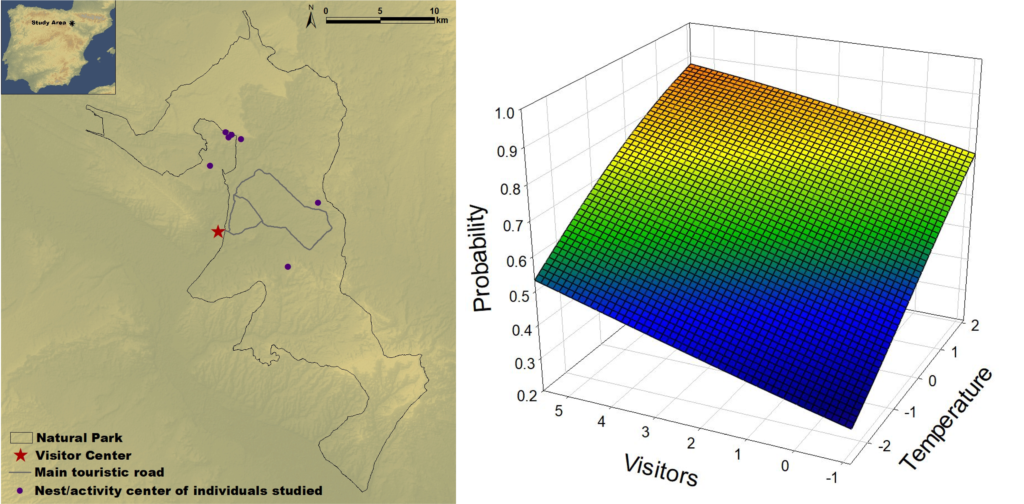

In order to provide more information on the impact of higher arrival of visitors in parks on avian scavengers we here use information yielded by seven GPS-tagged adult (three males and four females) resident Griffon Vultures (Gyps fulvus) captured in December 2015-January 2016. We examine changes in their movement patterns in response to variation in the number of visitors to Bardenas Reales Natural Park (Fig.1,2), in northern Spain. We obtained the daily numbers of persons visiting the park from records at the “information centre”, placed at the entrance of the protected area, as a proxy faithfully reflecting the numbers of visitors (Fig. 2).

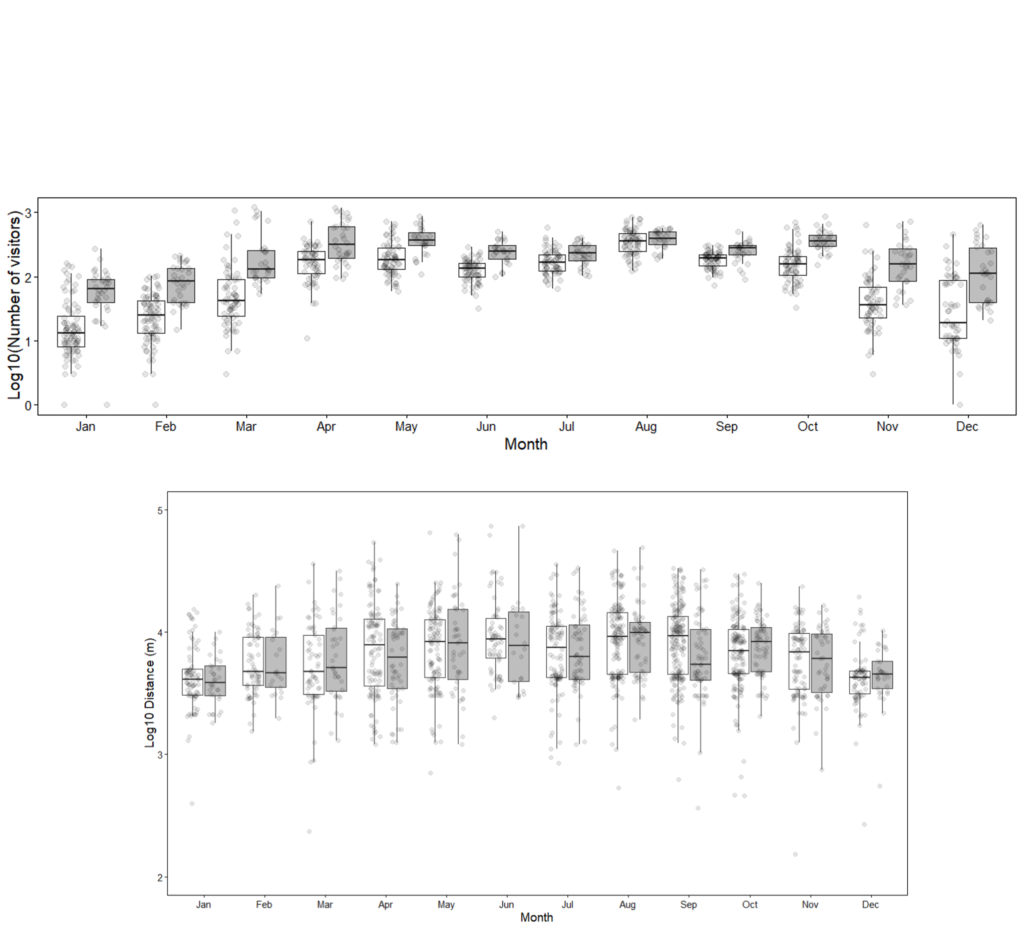

Most visits are concentrated during weekends and holiday periods of spring and summer, and during the middle of the day, giving rise to highly variable temporal patterns of visitor influx (Fig. 3 and see below and also Donázar et al. 2018 for more details).

We found that that the probability of a tagged vulture being in a position away from the visited area of the park was higher for those days with more visitors and higher temperatures and for male Fig 2,3).

A few years ago, we aimed at examining the impact of the raising arrival of tourist to Bardenas Reales Natural Park dynamics of large raptors and particular avian scavengers species by gathering information for example on the patterns of carcass consumption, breeding performance and other issues that may determine the viability of populations inhabiting the area.

This project required a large effort of fieldwork to capture and tagged birds wit GPS devices but also required of perform natural experiment and/or spend many hour of monitoring of breeding and feeding behavior, identify animals of camera trap photos.

In previous studies we found that on days with a higher traffic due to the arrival of visitors, the patterns of carcass consumption in the park by Griffon Vultures, Egyptian vulture together with other five species become altered. In particular, we found that the richness (number of species) and the probability of consumption of the resource were reduced the smaller the distance to the road and in days with higher traffic intensity.

Figure 2 Left: Study area in the Bardenas Reales Natural Park (northern Spain). The nests or activity centres of the GPS-tagged Griffon Vultures are shown by purple dots. – Right: Projection of the GLM analyses estimating the probability that GPS-tagged Griffon Vultures were above the median value of distance of the location of the bird in the middle hours of the day and the centre

The same factors affected the probability of presence of all the scavenger species (Donázar et al. 2018). In the present research work we analyses 1787 daily GPS locations of Griffon Vulture. This was the GPS position closest to solar noon within the 10.00-14.00h interval, corresponding to times of major flight and foraging activity.

In addition, this maximum activity of vultures coincides with the hours of the day with the highest number of visitors, so we believe that the positions obtained at that time are more likely to reflect a response of birds to human disturbance. It revealed that the probability of a tagged vulture being in a position away from the visited area of the park was higher for those days with more visitors and higher temperatures.

Moreover, we found that in general, males are located further away from the centre of the study area than females. This is surprising because females have larger foraging areas than males (Gangoso et al. 2021). This could possibly be due to a sex division of tasks. However, although occasional observations reveal a slightly greater role of females in incubation and care of young chicks, in general, the tasks seem shared between sexes (Elosegi 1989).

Figure 3 Upper panel: Number of visitors (log). Lower panel: Distance (m) between the daily positions of the vultures studied and the centre of the Bardenas Reales Natural Park (log). Data are shown per month, distinguishing working days (white) and weekends/long weekends (grey).

Human pressure on natural spaces has increased in Europe and worldwide over the last decades and particular after COVID19 restrictions with a sharply increasing even above previously observed levels of inflow of visitors. Overall, this study is relevant because on the one hand because is consistent with previous research in this line and because suggest that even small changes in foraging behaviour may result in the alteration of ecological functions.

Our findings suggest that future research studies should focus on smaller-scale approximations in order to determine how the behaviour of birds changes in response to the visitors. Probably, it would require fine-grained field measurements of tourist presence and habits in each area of the park. Moreover, determining vulture behaviour without direct observations would require the interpretation of accelerometers of GPS devices and specific scheduling of the transmitter devices.

Finally, we consider that measures will be needed to mitigate the negative effects without reducing the positive aspects of the interaction between visitors and nature (i.e. positive perception Cortés-Avizanda et al 2021)

References

Bautista, L.M., García, J.T., Calmaestra, R.G., Palacín, C., Martín, C.A., Morales, M.B., Bonal, R. & Viñuela, J. 2004. Effect of weekend road traffic on the use of space by raptors. Conservation Biology 76: 18: 726–732.

Cortés-Avizanda, A., Pereira, H.M., McKee, E., Ceballos, O. & Martín-López, B. 2012. Environmental Impacts of Tourism in Protected Areas. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2: 64–73

Buckley, R. 1991 (Ed). Environmental Impacts of Tourism in Protected Areas. Environmental impacts of recreation in parks and reserves bt – perspectives in environmental management pp. 243–258. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg

Silva, J.P., Correia, R., Alonso, H., Martins, R.C., D’Amico, M., Delgado, A., Sampaio, H., Godinho, C. & Moreira, F. 2021. Social actors’ perceptions of wildlife: Insights for the conservation of species in Mediterranean protected areas. Ambio 51: 990-1000

Dudley, N., Higgins-Zogib, L. & Mansourian, S. 2009. The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conserv. Biol. 23: 568–577

Elosegi, I. 1989. Vautour fauve (Gyps fulvus), gypaète barbu (Gypaetus barbatus), percnoptère d’Egypte (Neophron percnopterus): Synthèse bibliographiques et recherches. Acta Biologica Montana 3

Gangoso, L., Cortés-Avizanda, A., Sergiel, A., Pudifoot, B., Miranda, F., Muñoz, J., Delgado-González, A., Moleón, M., Sánchez-Zapata, J.A., Arrondo, E. & Donázar, J.A. 2021. Avian scavengers living in anthropized landscapes have shorter telomeres and higher levels of glucocorticoid hormones. Sci. Total Environ. 782: 146920

Malchrowicz-Mośko, E., Botiková, Z. & Poczta, J. 2019. ‘Because we don’t want to run in smog’: Problems with the sustainable management of sport event tourism in protected areas (A case study of national parks in Poland and Slovakia). Sustain. 11: 1–20

Penteriani, V., López-Bao, J.V., Bettega, C., Dalerum, F., Delgado, M. del M., Jerina, K., Kojola, I., Krofel, M. & Ordiz, A. 2017. Consequences of brown bear viewing tourism: A review Biol. Conserv. 206: 169–180

Perona, A.M., Urios, V. & López-López, P. 2019. Holidays? Not for all. Eagles have larger home ranges on holidays as a consequence of human disturbance. Biol. Biol. Conserv. 231: 59–66

Image credit

Top right: Gyps fulvus Juan Lacruz CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.