LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

The number of Great Tit mobbers influences the mobbing response of heterospecific birds. Dutour, M. & Cordonnier, M. 2023 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13224 VIEW

Life is dangerous for small birds. Many fall victim to predators, leading to the evolution of antipredator strategies to reduce the risks of predation. Usually, these strategies involve hiding or fleeing from predators. However, prey can sometimes engage in mobbing, where they gather around the predator, flying rapidly while making stereotypic movements and giving mobbing calls. Engaging in mobbing carries a degree of personal risk (Motta-Junior 2007), but the risk of injury or death declines, and the likelihood of repelling the predator increases, in larger groups (Hamilton 1971; Krams et al. 2009). The capacity to evaluate the number of individuals in a mobbing group could thus be highly beneficial for individuals when deciding to join. The ability to assess the number of individuals (conspecifics or heterospecifics) involved in mobbing events may be adaptive (Nieder 2020), however, this ability has been investigated in only a handful of bird species thus far (Coomes et al. 2019; Dutour et al. 2021; Dutour & Randler 2021).

To test whether the mobbing response of passerine birds is influenced by the size of the mobbing group, we used playback experiments by exposing a bird community to mobbing calls emitted by Great Tits (Parus major). This Paridae species is an ideal signaller species because (i) its mobbing calls convey information about the identity of the caller (Dutour et al. 2021), (ii) it produces mobbing calls that recruit conspecifics and heterospecifics to mob predators (Randler & Vollmer 2013), and (iii) it is considered as a ‘community informant’ species (i.e., a key information source; Carlson et al. 2020). Playbacks simulating calling by one or three Great Tits were used. In most cases, wild Great Tits did join in the calling, increasing the de facto number of callers to up to seven. The mix of callers simulated by the playbacks and live individuals attracted to the playback was therefore used to test the prediction that a larger number of callers would recruit both more individuals and species. Playbacks were conducted at 40 experimental sites. Great Tit calls were repeated for two minutes (Desrochers et al. 2002).

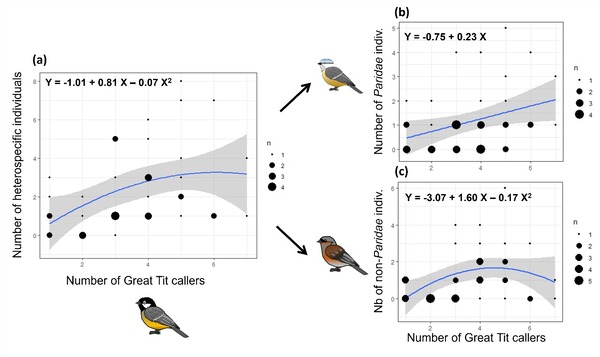

During the playback, observers counted the number of individuals approaching to within 15 m of the speaker and exhibiting mobbing behaviour. Eleven heterospecific species were observed within 15 m of the playback speaker. Species from the Paridae family were the most common among those that approached the speaker. The total number of responding heterospecifics was positively influenced by the total number of callers, with heterospecifics responding more to larger Great Tit groups, and with an optimum of responses for groups of five Great Tit callers. Interestingly, the maximum number of non-Paridae individuals responding was reached when five Great Tits were calling. Contrary to this response in non-Paridae species, the number of individuals responding to the Great Tits did not reach a maximum within the Paridae community: the number of responding individuals increased linearly with the number of callers.

Figure 1 The relationship between the total number of Great Tits (both live and playback callers) and the number of responding (a) heterospecific individuals, (b) Paridae individuals and (c) non-Paridae individuals.

This study suggests that European birds could take the number of callers into account when responding to Great Tit mobbing calls, and use a form of counting when deciding whether to join a mob.

References

Carlson, N. V., Healy, S. D., & Templeton, C. N. 2020. What makes a ‘community informant’? Reliability and anti-predator signal eavesdropping across mixed-species flocks of tits. Animal Behavior and Cognition 7:214-246. VIEW

Coomes, J. R., McIvor, G. E., & Thornton, A. 2019. Evidence for individual discrimination and numerical assessment in collective antipredator behaviour in wild jackdaws (Corvus monedula). Biology Letters 15:20190380. VIEW

Desrochers, A., Bélisle, M., & Bourque, J. 2002. Do mobbing calls affect the perception of predation risk by forest birds? Animal Behaviour 64:709-714. VIEW

Dutour, M. & Randler, C. 2021. Mobbing responses of great tits (Parus major) do not depend on the number of heterospecific callers. Ethology 127:379-384. VIEW

Dutour, M., Kalb, N., Salis, A., & Randler, C. 2021. Number of callers may affect the response to conspecific mobbing calls in great tits (Parus major). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 75:29. VIEW

Hamilton, W. D. 1971. Geometry for the selfish herd. Journal of Theoretical Biology 31:295-311. VIEW

Krams, I., Bērziņš, A., & Krama, T. 2009. Group effect in nest defence behaviour of breeding pied flycatchers, Ficedula hypoleuca. Animal Behaviour 77:513-517. VIEW

Motta-Junior, J. C. 2007. Ferruginous Pygmy-owl (Glaucidium brasilein) predation on a mobbing Fork-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus savana) in south-east Brazil. Biota Neotropica 7:321-324. VIEW

Nieder, A. 2020. The adaptive value of numerical competence. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 35:605-617. VIEW

Randler, C. & Vollmer, C. 2013. Asymmetries in commitment in an avian communication network. Naturwissenschaften 100:199-203. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Parus major © Luc Viator CC BY SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.