Report from a BOU Summer Placement Bursary

During the summer, I conducted research on the ecology of the Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) across Anglesey, North Wales, as part of the BOU Summer Placement Scheme. One of my study sites overlooked Puffin Island, located off the eastern tip of Anglesey, which supports the largest coastal colony of great cormorants in the UK, with 476 pairs recorded in the 2018 census. Because of its importance, the island is designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Despite this designation, the ecology of great cormorants at Puffin Island remains poorly understood, with most ornithological studies in the region focusing instead on the European Shag (Gulosus aristotelis) (Soanes et al., 2013, 2014) or the Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla) (O’Hanlon et al., 2024).

Figure 1. Puffin Island, in the Menai Strait.

Figure 1. Puffin Island, in the Menai Strait.

Meanwhile, Great Cormorant populations in Wales have shown declines in recent decades (Burnell et al., 2023; Chamerlain et al., 2013), alongside additional pressures from expanding offshore wind-farm developments. Improving understanding of cormorant ecology in this region is therefore essential to support environmentally sustainable and responsible management of marine activities.

Through this project, I combined a range of land- and boat-based methodologies to build a baseline understanding of great cormorant ecology at Puffin Island and surrounding waters.

Fieldwork and Data Collection

My fieldwork combined shore-based, boat-based, and camera-data approaches. I conducted extended vantage point surveys near Penmon Point, at the entrance to the Menai Strait, with multi-day surveys lasting up to 15 hours. These observations captured temporal variation in cormorant activity across different tidal cycles and weather conditions.

Figure 2. Author (Rebecca Gillmore) conducting boat survey work across Anglesey.

Figure 2. Author (Rebecca Gillmore) conducting boat survey work across Anglesey.

At sea, I carried out surveys aboard Bangor University’s research vessel, the RV Prince Madog, as part of the ACCELERATE project, which investigates the ecological impacts of offshore wind developments. The cruise provided opportunities for me to contribute to seabird observations, distance sampling, and prey distribution studies using echosounders and rockhopper otter trawls at key locations across the Conwy Bay area.

Alongside field observations, I analysed time-lapse camera data from 2021, 2022, and 2023 to investigate patterns of roost and nest attendance. This involved using specialist annotation software (DotDotGoose) and applying statistical techniques in R.

Figure 3. An example image taken from the time-lapse photography.

Figure 3. An example image taken from the time-lapse photography.

Methodological Approaches and Findings

I used a multi-faceted approach to build a comprehensive picture of cormorant ecology in the region. Time-lapse photography provided insights into breeding behaviour and daily activity rhythms, while systematic vantage point and boat-based surveys produced data on at-sea distribution, abundance, and activity patterns. I followed standardised methodologies, such as the ESAS (European Seabirds at Sea) protocols, to ensure robust and comparable data collection.

Figure 4. Rebecca pictured in School of Ocean Science fish lab, extracting muscle samples from fish taken from the trawls.

Figure 4. Rebecca pictured in School of Ocean Science fish lab, extracting muscle samples from fish taken from the trawls.

I conducted laboratory analyses on fish to collect muscle samples of various types of fish, for Stable Isotope Analysis (SIA) across multiple years to investigate trophic relationships and dietary patterns. Prey availability and diet composition were further examined through a combination of echosounder surveys and rockhopper otter trawls. Laboratory analyses conducted at Bangor University enabled me to identify fish species and characterise prey composition through dissections, SIA, and lipid extraction. These methods were integrated with ongoing population and productivity monitoring at Puffin Island, carried out in collaboration with Bangor and Liverpool universities. Collectively, these complementary approaches provided novel ecological insights and established a foundation for the long-term monitoring and conservation of the colony.

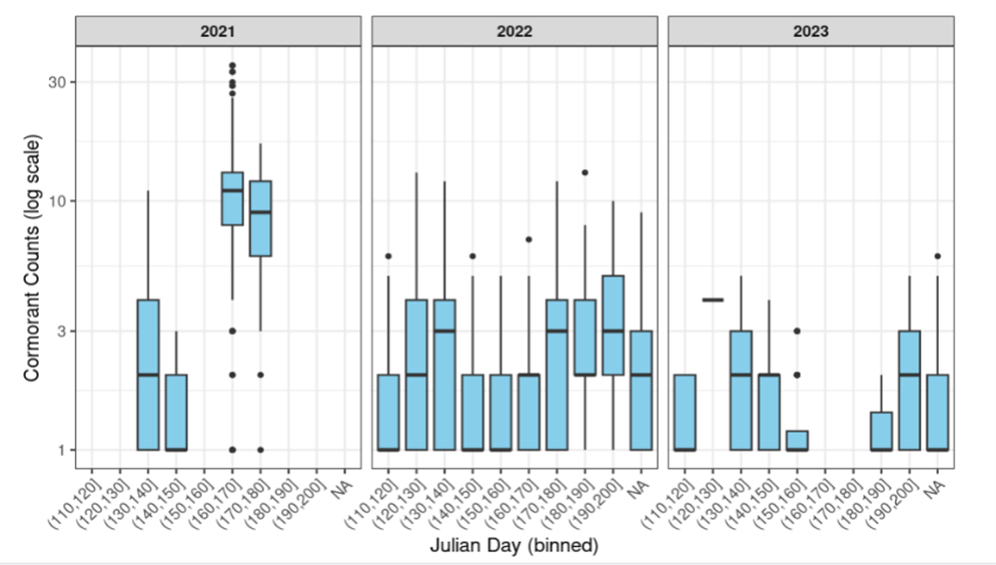

My analysis of time-lapse camera data from 2021–2023 revealed clear interannual variation in cormorant attendance patterns. In 2021, counts increased sharply mid-season, indicating a concentrated period of activity and high roost use. In contrast, 2022 displayed more intermittent but relatively consistent attendance across the year, while 2023 showed lower overall counts with more evenly distributed attendance. Field observations also indicated that cormorants were markedly less active during periods of easterly winds, suggesting reduced foraging efficiency and prey accessibility under these conditions. This could also indicate that they switch habitats in challenging wind conditions and periods of high precipitation (Frederiksen et al., 2008).

Figure 5. The cormorant counts across years, 2021, 2022, and 2023. Counts taken from time-lapse images.

Figure 5. The cormorant counts across years, 2021, 2022, and 2023. Counts taken from time-lapse images.

Together, these methods and findings provided new insights into cormorant ecology at Puffin Island and laid the groundwork for long-term monitoring of the colony.

Training and Skills Development

This project offered extensive training opportunities in seabird ecology and marine research. I gained experience in vantage point and European Seabirds At Sea methodologies, species identification, and distance sampling, alongside advanced statistical analysis using GLMs and GAMs in R. I also developed skills in time-lapse camera deployment and image annotation techniques, while sea-based work expanded my understanding of survey design, prey distribution studies, and fish identification. These experiences have strengthened my field and analytical skills, which I can apply to future ecological research.

Collaboration and Support

This work benefited from strong collaboration and institutional support. Within Bangor University’s School of Ocean Sciences, I was integrated into the Marine Top Predator Research Group, which provided access to expertise and opportunities for collaboration. I also made use of laboratory facilities and received fisheries expertise to support stable isotope analysis. The placement was closely aligned with the ACCELERATE (EcoWIND) project, which funded research cruises on the RV Prince Madog and enabled me to participate in a large interdisciplinary research effort.

Future Direction

The methods I developed and applied during this placement provide a strong basis for long-term monitoring of Great Cormorants at Puffin Island. Continued application of these approaches would significantly enhance understanding of the pressures facing the population and contribute to the sustainable management of North Wales’ marine environment.

Figure 6. Cormorants on the roost, Puffin Island, Wales.

Figure 6. Cormorants on the roost, Puffin Island, Wales.

Conclusion

This BOU-funded summer placement enabled me to develop an integrated research programme on the ecology of the great cormorant at Puffin Island. By combining land-based surveys, boat-based work, and time-lapse imagery analysis, I gained valuable insights into the behaviour and ecology of this understudied species. The placement also provided substantial training in seabird survey methods, statistical analysis, and collaborative research, establishing a strong foundation for my future work in seabird ecology and conservation.

Acknowledgements

With special thanks to Dr James J Waggitt from the School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, for supporting this project and for his unwavering guidance.

References

Soanes, L. M., Arnould, J. P., Dodd, S. G., Sumner, M. D., & Green, J. A. 2013. How many seabirds do we need to track to define home‐range area?. Journal of Applied Ecology 50(3):671-679.VIEW

Soanes, L. M., Arnould, J. P. Y., Dodd, S. G., Milligan, G., & Green, J. A. 2014. Factors affecting the foraging behaviour of the European shag: implications for seabird tracking studies. Marine Biology 161(6):1335-1348.VIEW

O’Hanlon, N. J., Thaxter, C. B., Clewley, G. D., Davies, J. G., Humphreys, E. M., Miller, P. I., Pollock, C. J., Shamoune-Baranes, J., Weston, E. & Cook, A. S. C. P. 2024. Challenges in quantifying the responses of Black-legged Kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla to habitat variables and local stressors due to individual variation. Bird Study 71(1):48-64.VIEW

Burnell, D. et al. 2023. Seabirds Count: Census of Breeding Seabirds in Britain and Ireland (2015–2021).VIEW

Chamberlain, D. E., Austin, G. E., Green, R. E., Hulme, M. F., & Burton, N. H. K. 2013. Improved estimates of population trends of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo in England and Wales for effective management of a protected species at the centre of a human–wildlife conflict. Bird Study 60(3):335-344.VIEW

Frederiksen, M., Daunt, F., Harris, M. P., & Wanless, S. 2008. The demographic impact of extreme events: stochastic weather drives survival and population dynamics in a long‐lived seabird. Journal of Animal Ecology 77(5):1020-1029.VIEW

Image credit

All images were taken by © Rebecca Gillmore.