LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Using mitochondrial DNA to identify the provenance of 19th century Kākāpō skins held in Australia’s oldest natural history collection, the Macleay. Mudge, C., Gray, L.J. & Austin, J.J. 2021 Emu. doi: 10.1080/01584197.2021.1998782 VIEW

It was about 2011. In the midst of my PhD, I was procrastinating by wandering about the basement of the University of Sydney’s Badham Library, “getting some air”. A suitably bleak setting for student procrastination. In those days, there were some old museum stores underneath the library, and when I saw that one of the room’s doors was ajar, I couldn’t help but peep through the crack as I passed by.

The light I was on, so I got a good view of the slightly spooky insides. There were shelves and shelves of bottled specimens and mounted skeletons on plinths. There was also my friend Robert Blackburn. I’d taken undergraduate classes with Robert and hadn’t seen him for some time. So I bravely opened the door fully, took in that special stench of naphthalene, and said “hi”.

Figure 1 “Juvenile Kakapo” © Kimberley Collins CC BY 2.0.

Robert was working as a curator in the Macleay Museum (now the Macleay Collections of the Chau Chak Wing Museum) at the University of Sydney. Robert obliged my interest. Knowing I’d recently returned from New Zealand, he delighted in showing me the diversity of 1800’s zoological materials Sir William John Macleay had acquired from Aotearoa/New Zealand from his fellow museum directors Sir James Hector and Sir Julius von Haast.

Robert opened up two drawers full of study skins. Much to my amazement, the reams of smelly green objects in the drawers were, of all things, Kākāpō (Strigops habroptilus). About 20. Kākāpō are exceptional, quirky birds. They are from the oldest lineage of parrots, and are flightless, smelly, and unusually for parrots, lek-breeding (Merton et al. 1984). Like all students of evolution, New Zealand’s bizarre birds had always fascinated me, but knowing how seriously rare Kākāpō were (and still are), seeing these birds laid out flat, looking so near perfect, but also very dead, was plainly tragic. At the time there were only about 150 living Kākāpō (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Macleay Collection Kakapo skins © Matthew Renner.

The modern explanation for the vastness of 19th Century zoological collections is that Macleay and his ilk were collecting and preserving skin specimens in large numbers for “conservation”. They were purportedly saving a record of Earth’s biodiversity for science and study in perpetuity.

These specimens were called “study specimens”, however, very little post-preservation study of 19th Century museum specimens actually occurred. Well, until relatively recently.

A growing number of 21st Century Biologists are using museum study skins to inform basic species biology, conservation management, and science history. Proving particularly useful are specimens of rare species – like Kākāpō. And it’s just as well scientists have turned their attention to these specimens now, as we don’t really know how much longer the old skins will keep, despite the copious naphthalene.

But back to Robert in 2011. Robert encouraged my interest, and frankly, sadness, that day and let me know that the Macleay Museum had a modest fellowship programme, the Macleay Miklouho-Maclay Fellowship. He said I should apply to study the many Kākāpō specimens – to try and put right the excesses of scientists past.

Fast forward 10 years and our little team has tried to do just that. During my fellowship I was lucky to partner with Caitlin Mudge and Jeremy Austin from the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA. Together we set ourselves two goals. A common issue with old museum specimens is that the origin or “provenance” of the specimen is questionable, or totally unknown. This seriously limits their ethnographic and scientific value. So, building on earlier work that used the skin’s stuffing to estimate provenance (Gray and Renner 2016), we used ancient DNA techniques to try and resolve the provenance problem. Second, having obtained the bird’s genetic information, we wanted to work out the genetic distinctness of the Macleay Kākāpō and help to quantify just how much genetic diversity Kākāpō have lost since their near extirpation began in the 1800s.

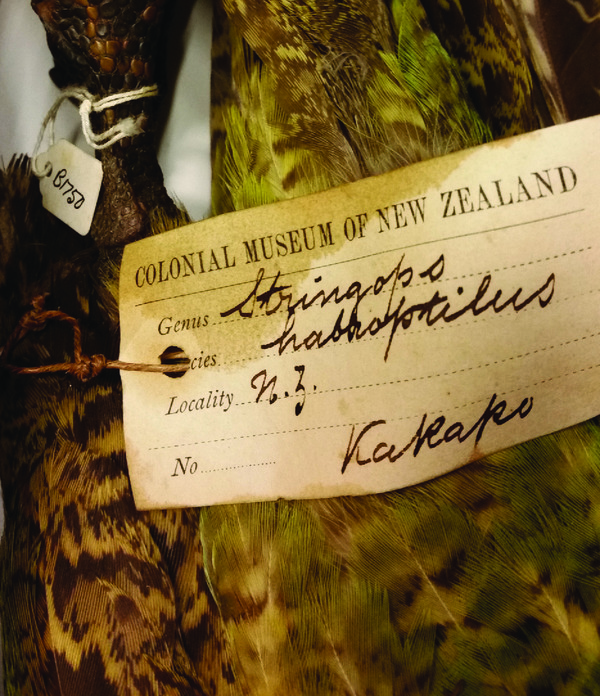

Figure 3 An original Colonial Museum specimen swing tag with no provenance information beyond “New Zealand”.

To achieve these goals we took small skin samples from the specimen’s abdominal walls and toe-pads. Caitlin and Jeremy then did all the hard laboratory and computational work. In the ancient DNA lab they minced up the old preservation chemical laden skin samples using fine scalpels and extracted each bird’s 150-year-old mitochondrial DNA.

Figure 4 Sampling a Macleay Kakapo for aDNA analysis © Robert Blackburn.

First, they determined whether the Macleay Kākāpō were collected on the North or South Island. Not even that was known. They used PCR amplification and then Sanger sequenced a 214 base-pair section of the Kākāpō mtDNA-control region from each specimen. This particular region was important as its sequence was already known and published for 22 historical, sub-fossil Kākāpō specimens that were definitely from the North Island, and 96 certified South Island origin Kākāpō (see Bergner et al. [2016] and Seersholm et al. [2018]). Next, they compared haplotypes of the unknown Macleay specimen sequences against haplotypes of the “provenanced” specimens using PopART, and demonstrated unequivocally that the Macleay birds had come from the South Island.

To further explore the geographic origins of the Macleay Kākāpō, Caitlin and Jeremy generated complete mtDNA genome sequences for each specimen. Fortunately, an existing programme, Kākāpō 125+, dedicated to documenting all living and some historical Kākāpō genomes, was underway. As part of that programme, Dussex et al (2018) had already published full 118 mtDNA genomes from contemporary and historical birds of known origin. Caitlin and Jeremy were able to phylogenetically compare, once again, the “unknown” Kākāpō genomes to the Kākāpō genomes of “known” geographical origin, but at a finer geographical scale than the previous analysis.

Every one of the Macleay Kākāpō specimens analysed had a unique genetic signature, indicating that none of the Macleay samples were close maternal relatives. This corroborates earlier findings of high mtDNA diversity in Kākāpō prior to population declines. This finer scale analysis also found that seven of the Macleay Kākāpō were most closely related to historical Kākāpō known to have come from the Southern west coast of the South Island, probably from either Milford Sound, the Arawhata Mountains, or Jacksons Bay. Another Macleay Kākāpō was determined to have been collected in Fiordland, and the ninth specimen was likely from Otago. These results suggest three separate collection events occurred, and in our paper, we conduct some archival analyses and speculate on who undertook these collection expeditions and when.

So, we were able to determine the collection location for the birds as best we could with current reference materials. We were also able to contribute detailed genetic information for an additional nine historical Kākāpō which will hopefully serve as an important resource for future studies of Kākāpō genomic diversity.

Happily, modern conservation techniques are far less gothic, and dedicated predator control, monitoring, and managed breeding have seen the Kākāpō population swell to 252. To learn more about Kākāpō and the species conservation efforts, visit here.

References

Merton, D. V., Morris, R. B. & Atkinson, I. A. E. 1984. Lek behaviour in a parrot: the Kākāpō Strigops habroptilus of New Zealand. Ibis 126: 277-283. VIEW

Gray, L.J. & Renner, M. A. M. 2016. Botany, GIS and archives combine to assess the provenance of historical Kākāpō study-skins stuffed with New Zealand bryophytes. Emu 116: 452-460. VIEW

Bergner, L. M., Dussex, N., Jamieson, I. G. & Robertson, B. C. 2016. European colonization, not polynesian arrival, impacted population size and genetic diversity in the critically endangered New Zealand Kākāpō. Journal of Heredity 107: 593-602. VIEW

Seersholm, F. V., Cole, T. L., Grealy, A., Rawlence, N. J., Greig, K., Knapp, M., Stat, M., et al. 2018. Subsistence practices, past biodiversity, and anthropo- genic impacts revealed by New Zealand-wide ancient DNA survey. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 7771. VIEW

Dussex, N., Von Seth, J., Robertson, B. C. & Dalen, L. 2018. Full mitogenomes in the critically endangered Kākāpō reveal major post-glacial and anthropogenic effects on neutral genetic diversity. Genes 9: 220. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: “Kenneth” Strigops habroptilus (Kākāpō) © Jake Osborne CC BY NC SA 2.0 Flickr.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.