LINKED PAPER

Evaluating cropland in the Canadian prairies as an ecological trap for the endangered Burrowing Owl Athene cunicularia. Scobie, C. A., Bayne, E. M. & Wellicome, T. I. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12711. VIEW

Canadian populations of Burrowing Owl Athene cunicularia declined by over 90 percent over the last 30 years. This decline might be due to human-induced habitat change. During the past century, the widespread grasslands of Canada have been converted into agricultural croplands. Such rapid habitat changes can result in an ecological trap, which refers to the situation where animals choose habitats that lower their reproductive output (Pärt et al. 2007). Perhaps Burrowing Owls are choosing the same nesting sites as before the transition into croplands, even though these locations have deteriorated in quality. A group of Canadian researchers put this idea to the test by monitoring about 400 nests in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Annual Crops

Burrowing Owls mostly eat small mammals (Poulin & Todd 2006). Agricultural fields are characterized by short vegetation and bare soil at the beginning of the breeding season. These locations are perfect for detecting and capturing prey and might thus be preferred by Burrowing Owls (Marsh et al 2014). And indeed, owls that arrived early at the Canadian breeding grounds choose nesting sites surrounded by annual crops. Because these early birds had first pick, this suggests that they prefer these sites.

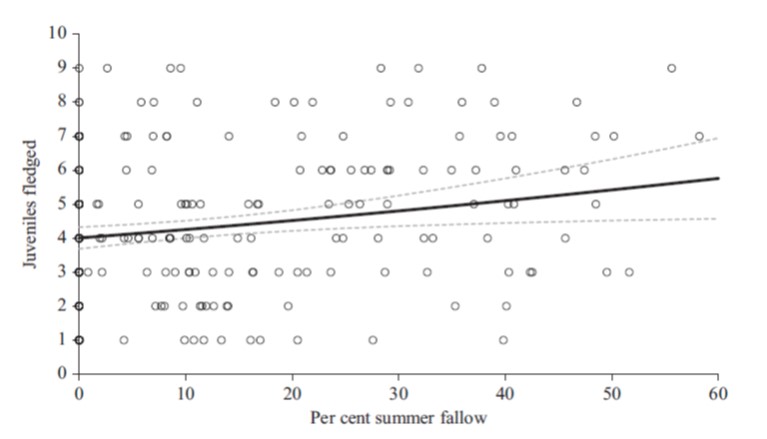

If there is an ecological trap, there should be a negative relationship between the percentage of annual crops around a nest and the number of fledglings. This was, however, not the case. In fact, more owlets fledged in areas with more annual crops. It seems that Burrowing Owls are making the right choice.

Figure 1 Relationship between number of juveniles fledged and percentage of cropland (summer fallow) surrounding the nest. Owls that choose nesting sites with more cropland have more fledglings, indicating that they are not in an ecological trap.

Generalist

There is thus no evidence for an ecological trap during the breeding season. Possibly, the ecological trap operates at a different life stage, such as the survival of the fledglings. Another study found that fledglings survive better in nests with large patches of grasslands compared to isolated nests in small patches (Todd et al. 2003). Alternatively, the owls are not stuck in any ecological trap. Burrowing Owls are generalists that can quickly adapt to environmental changes and might avoid wandering into an ecological trap.

References

Marsh, A., Wellicome, T. I. & Bayne, E. 2014. Influence of vegetation on the nocturnal foraging behaviors and vertebrate prey capture by endangered Burrowing Owls. Avian Conservation and Ecology 9: 2. VIEW

Pärt, T., Arlt, D. & Villard, M. A. 2007. Empirical evidence for ecological traps: a two-step model focusing on individual decisions. Journal of Ornithology 148: 327-332. VIEW

Poulin, R. G. & Todd, L. D. 2006. Sex and Nest Stage Differences in the Circadian Foraging Behaviors of Nesting Burrowing Owls. The Condor 108: 856-864. VIEW

Todd, L. D., Poulin, R. G., Wellicome, T. I. & Brigham, R. M. 2003. Post-Fledging Survival of Burrowing Owls in Saskatchewan. Journal of Wildlife Management 67: 512-519. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: Burrowing Owl Athene cunicularia | Alan D. Wilson | CC BY-SA 2.5 Nature’s Pics Online