LINKED PAPER

Predation on artificial avian nests is higher in forests bordering small anthropogenic openings. Valentine, E.C., Apol, C.A. & Proppe, D.S. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12662 VIEW

Human activities often lead to habitat fragmentation. For example, large forests are crisscrossed with roads, resulting in patchwork of forest fragments with more edges bordering open areas. Birds nesting at these forest edges could be more vulnerable to predation. Indeed, several studies documented increased nest predation at forest edges (e.g., Bosz et al. 2017). But what about forest perforations, small gaps in a continuous forested area. A group of American ornithologists investigated this question by taking advantage of the oil and gas extraction activities in North America (Van Wilgenburg et al. 2013). These extractions mostly occur in remote areas where a small section of forest is cut clear.

Artificial nests

The researchers travelled into the dense forests of Michigan (USA) and placed artificial nests at the edges of forest clearings and several meters (5, 20 or 35 meters) into the forest. The nests were based on three local species. The Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) constructs domed ground nests using twigs and grasses, while the Chestnut-sided Warbler (Setophaga pensylvanica) builds open nests in shrubs. Mimicking the nests of these two species allowed the researchers to compare the effects of forest edges on ground and shrub nesting birds. The third species in this study is the Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), which lays eggs in a small indentation on the ground. The artificial nests of Ovenbirds and Chestnut-sided Warblers were filled with clay eggs and the Northern Bobwhite nests contained live eggs from a gamebird farm.

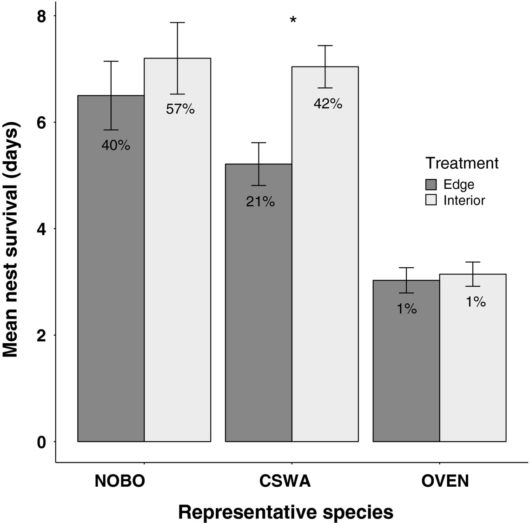

Figure 1 Mean nest survival for artificial nests representing three species: the Northern Bobwhite (NOBO), the Chestnut-sided Warbler (CSWA) and the Ovenbird (OVEN). Nest survival was always higher in the forest, but only significant for the Chestnut-sided Warbler.

Predators

The results from this experiment revealed that predation rates were elevated at the forest edges. However, the effect was only significant in the shrub nests of the Chestnut-sided Warbler. This finding can probably be explained by the identity of the local predators (Söderström et al. 1998). Forest perforations and shrub nests are more easily located by flying predators, such as American Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and Blue Jays (Cyanocitta cristata). A survey of the area indicated that these species are indeed more common at forest edges. Moreover, mammals (which mostly predate nests on the ground) are less likely to discover the forest clearings in a large continuous forest (Lindtsteds et al. 1986).

This study provides important insights into the predation dynamics at forest edges. But it is difficult to extrapolate these experimental results (based on artificial nests) to natural settings (Zanette 2002). For example, adult birds were not present at the artificial nests. Their presence could provide predators with extra information about the location of the nest. Hence, more research – preferably using natural nests – is needed here.

References

Bocz, R., Szép, D., Witz, D., Ronczyk, L., Kurucz, K., & Purger, J. J. (2017). Human disturbances and predation on artificial ground nests across an urban gradient. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 40: 153-157. VIEW

Lindstedt, S. L., Miller, B. J., & Buskirk, S. W. (1986). Home range, time, and body size in mammals. Ecology 67: 413-418. VIEW

Söderström, B., Pärt, T., & Rydén, J. (1998). Different nest predator faunas and nest predation risk on ground and shrub nests at forest ecotones: an experiment and a review. Oecologia 117: 108-118. VIEW

Van Wilgenburg, S., Hobson, K., Bayne, E., & Koper, N. (2013). Estimated avian nest loss associated with oil and gas exploration and extraction in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Avian Conservation and Ecology 8: 9. VIEW

Zanette, L. (2002). What do artificial nests tells us about nest predation? Biological conservation 103: 323-329. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: Chestnut-sided Warbler Setophaga pensylvanica | Cephas | CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons