LINKED PAPER  Reconnecting children to nature: The efficacy of a wildlife intervention depends on local nature and socio-economic context, but not on urbanisation. Kjellberg Jensen, J., Olsson, J.A., von Post, M., Isaksson, C. 2024. People and Nature. DOI: 10.1002/pan3.10702. VIEW. This work was presented at the BOU Urban Birds conference in April 2024.

Reconnecting children to nature: The efficacy of a wildlife intervention depends on local nature and socio-economic context, but not on urbanisation. Kjellberg Jensen, J., Olsson, J.A., von Post, M., Isaksson, C. 2024. People and Nature. DOI: 10.1002/pan3.10702. VIEW. This work was presented at the BOU Urban Birds conference in April 2024.

When did you first become interested in birds, or nature in general? Was there any pivotal moment that opened your eyes to the outdoors and everything in it, sparking a drive to experience more of it? If you are like most people with an interest in nature, such a moment –or several– probably happened already in your youth. Today, however, those treasured moments could be at risk of going extinct.

Already in the 1970s Robert M. Pyle, American scientist and writer, warned about what he coined to be an extinction of experience. The idea is quite simple. As society moves away from nature and into cities, children’s experiences with nature are becoming rarer due to our growing detachment from these natural settings. For example, seeing a Hen Harrier floating over the fields, a Kingfisher diving in a stream, or hearing a Golden Oriole’s song are all very uncommon experiences for children growing up in cities. And the extinction of nature experiences like these comes with consequences: for one, having fewer early experiences of nature makes us less likely to seek out nature later in life. An increasing number of studies are showing multiple health benefits of spending time in nature, but people may miss out on these ecosystem services by staying indoors. Another problem is the future of conservation. People care the most about things in their proximity, that they know of, and have a relationship to. One study in the early 2000s showed that British school children had better “species knowledge” of Pokémon, than common wildlife. The authors reasoned that this was because the Pokémon simply were more relevant to the children’s everyday lives than local animals. If nature no longer is relatable, the future of conservation may be bleak.

How do we reverse this trend? Bird feeding has for a long time been suggested by scientific studies as a possible tool to strengthen children’s connection to nature. And it has a lot going for it: birds are well-liked through their appearance and song, they are widespread and easy to observe, and feeding them can create a sense of local stewardship – a powerful motivator for conservation. However, the key question remains unanswered. Is bird feeding a viable remedy for the extinction of experience?

That is what we sought to find out in our study, whether interactions with birds on the feeding table actually can reconnect children with nature and what circumstances may moderate the effect. Circumstances like if you are growing up in a city or the countryside, in a relatively rich and well-educated area or a socioeconomically weaker area, and whether or not you have nature to play in near your residence. We worked with 10–11-year-old pupils in schools across southern Sweden, specifically selected to represent varying circumstances. Our study design was simple: survey the children before and after a three-week-long bird feeding and monitoring program at the school. We quizzed the kids on their species knowledge, attitude towards birds, and wellbeing. Would there be any differences before and after feeding the birds and would the circumstances mentioned above affect the outcome?

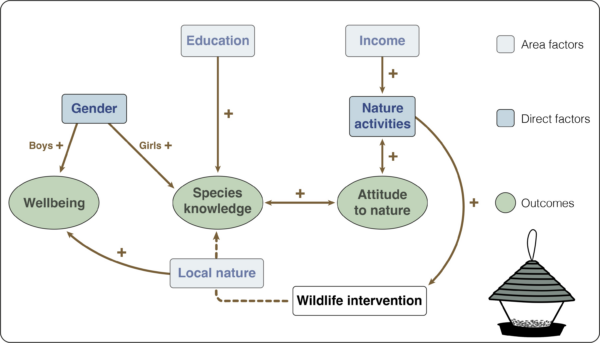

What we found surprised us. We saw no difference between kids growing up in urban areas or the countryside in terms of their pre-existing species knowledge or attitudes towards birds. Somewhat contrary to the idea of the extinction of experience, it was instead local income and education levels that governed the children’s relationships with nature. Children in richer areas participated in more outdoor nature activities, and children in well-educated areas knew more species. Both these factors predicted positive relationships with birds (Figure 1). This suggests socioeconomics, rather than if you grow up in a city, is what shapes your relationship to nature. We did, however, find that urban and rural children utilize nature in different ways. For example, kids growing up in cities tended to associate nature with social activities more than their countryside peers. Previous studies have highlighted how traffic can restrict children’s mobility and that some parents view urban greenspaces as unsafe. Our results may reflect that urban children are less likely to spend time in nature unsupervised.

Figure 1. Conceptual figure from paper showing correlations as a flowchart.

But for the main question: what were the effects of bird feeding? We did not find a direct impact on attitudes towards birds, but we did find a marked increase in species knowledge. Interestingly, this increase was the largest for the children who had no nature to play in around their homes. This finding suggests children have an innate interest in nature and will engage with it given the opportunity. Further underscoring the importance of having proximity to nature, we found that children with more nature around their homes also reported significantly higher wellbeing. A key conclusion to draw from this is just how important it is for children to have proximity and access to nature in their everyday lives, both in and outside of cities.

Regarding bird feeding as a tool to reconnect, is the conclusion then that bird feeding does not improve children’s relationships with nature? Not precisely – a crucial context to our findings is a very large variation between schools, which we could not attribute to the circumstance we tested for (e.g. socioeconomics).

A piece of the story is missing. So, let’s go back to the start, to the memory of when you first became interested in nature. For many, formative childhood experiences of nature might not have been about the specific bird or landscape, but rather about the person that you shared the experience with. Perhaps a parent or grandparent teaching you about birds: a role-model. We hypothesize that the large differences we see between schools are about the teachers and their ability, and possibility, to facilitate nature connection in their classes. This is in line with previous studies that underscore social context being vital to forming positive nature relationships.

In conclusion, can bird feeding nurture future generations’ nature relationships? Yes, to an extent, and reconnecting is especially needed in areas with low socioeconomic levels and areas that lack local nature, both in cities and elsewhere. But crucially, bird feeding only works to reconnect children to nature given the right conditions, which includes guiding role-models that use the bird feeder as a tool to teach and inspire. Who will that be? That is a question beyond our study, but we are hesitant to suggest further burdening the already vast responsibilities of teachers. Instead, it will perhaps be some of the nature-committed bird lovers, reading about the latest ornithology news on a conservation trust’s blog today.

Image credit

Top right: Feeding birds © Diego Cambiaso.