LINKED PAPER

Recent trends in populations of Critically Endangered Gyps vultures in India. Prakash, V., Bajpal, H., Chakraborty, S.S., Mahadev, M.S., Mallord, J.W., Prakash, N., Ranade, S.P., Shringarpure, R.N., Bowden, C.G.R., Green, R.E. 2024. Bird Conservation International. DOI:10.1017/S0959270923000394 VIEW

The goal of most conservation actions is to have a positive impact on your population of interest. Ultimately, this often involves halting population declines and, hopefully, seeing a recovery in numbers of your target species.

When talking of avian population declines, few recent examples can compare with the plight of Gyps vultures in South Asia. Historically considered some of the most abundant species of large raptor in the world, their populations underwent catastrophic declines from the mid-1990s onwards, as a result of unintentional poisoning by the veterinary drug diclofenac (Green et al. 2007, Prakash et al. 2017). The worst-hit species, White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis, declined by 99.9% in India between 1992 and 2007. As a result, three species endemic to South and South-east Asia, White-rumped, Indian G. indicus and Slender-billed G. tenuirostris Vultures, were classified by IUCN as Critically Endangered.

Diclofenac was banned in India and elsewhere in 2006, since when concerted efforts, including widespread advocacy and education, have been made to ensure the drug remains absent from the vultures’ food supply. Along with these conservation actions, vulture numbers have been monitored on a regular basis to assess whether the efforts are having any impact on the status of populations of these endangered species.

Beginning in 1992, vultures in India have been surveyed along road transects, which involves driving along both major highways, and tracks running through protected areas, and counting any vultures encountered (Figure 1). The eighth such survey, which covered over 16,000 km of roads in 13 states in north, west and central India, was carried out in 2022, and the results have recently been published.

Figure 1. Team from Bombay Natural History Society carrying out road transect surveys in north India © Sachin Ranade

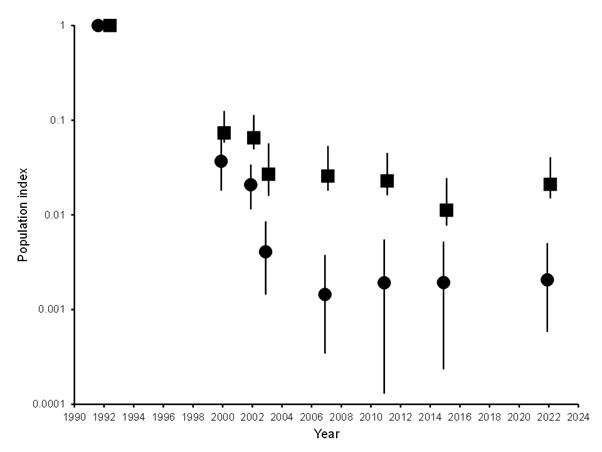

Previous surveys up to 2015 had shown that the rapid declines that White-rumped and Indian and Slender-billed Vultures combined (the latter wasn’t recognised as a separate species until 2002) had experienced from the mid-1990s onwards had begun to slow down, with even some tentative evidence that populations of White-rumped had stabilised (Prakash et al. 2017). Numbers of Slender-billed Vultures have always been too low to quantify a reliable trend for this rare species. Survey results from 2022 confirmed that populations continued to remain stable, including Indian Vulture, which had shown signs of further declines in the 2015 survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Indices and trends of populations of White-rumped Vulture (circles) and of Indian and Slender-billed Vultures combined (squares) in northern India, based on counts from road transect surveys, 1992-2022.

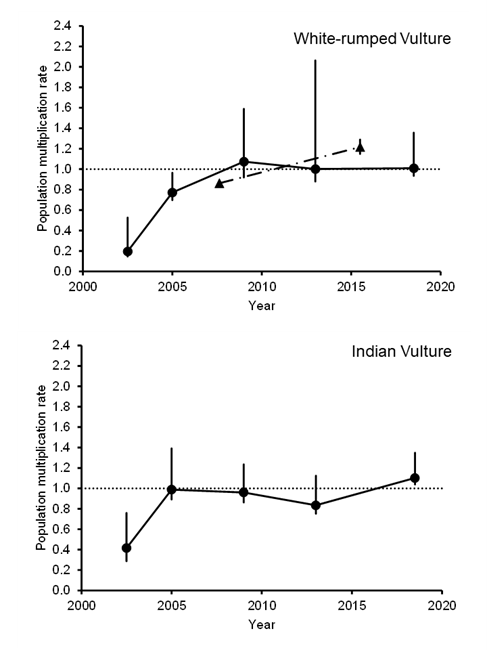

Further evidence that populations have remained stable came from analysis of changes over time in the annual population multiplication rate, which was below one (indicating a population decline) in the early 2000s, but which hovered around one (stability) in later periods (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Annual population multiplication rates for White-rumped Vulture in northern India (circles) and Nepal (triangles), and Indian Vulture in northern India. For India, rates were averaged between each consecutive pair of surveys; for Nepal, estimates are for two periods: (2002-2013 and 2013-2018). The horizontal dashed line indicates stable population size.

Unlike in India, in Nepal population indices of WRV and SBV have both shown significant increases over recent years, with population multiplication rates greater than the maximum intrinsic rate likely under optimum conditions (Galligan et al. 2020). Possibly the main reason for these differences is the different status of diclofenac and other vulture-toxic NSAIDs in the two countries. Whereas undercover pharmacy surveys have demonstrated that human formulations of diclofenac are still widely offered for veterinary care in India, the drug has all but disappeared from veterinary pharmacies in Nepal (Galligan et al. 2021). Aided by the early efforts of the Nepal government in instigating a meloxicam (earlier shown to be safe for vultures to consume; Swan et al. 2006) for diclofenac substitution scheme, the vulture-safe drug has become the drug of choice for farmers treating their cattle.

Despite populations of vultures remaining stable since the ban on diclofenac, much work remains to be done to ensure the future survival of these species. With population levels now at a fraction (1/500th and 1/50th of levels in 1992 for WRV and IV, respectively), the species are still in a precarious situation. Although there was welcome news earlier in 2023 that veterinary use of two more vulture-toxic drugs, ketoprofen and aceclofenac, were to be banned in India, there is still no process in place that would prevent new drugs from coming on to the market until their safety to vultures is confirmed. This, along with the continued legal use of the vulture-toxic NSAID nimesulide, and other potentially lethal drugs that have not been tested, leaves vultures still at risk of imminent extinction at the hands of toxic veterinary drugs.

References

Galligan, T.H., Bhusal, K.P., Paudel, K., Chapagain, D., Joshi, A.B., Chaudhary, I.P., Chaudhary, A., Baral, H.S., Cuthbert, R.J., Green, R.E. 2020. Partial recovery of Critically Endangered Gyps vulture populations in Nepal. Bird Conservation International 30:1. VIEW

Galligan, T.H., Mallord, J.W., Prakash, V.M., Bhusal, K.P., Alam, A.B.M.S., Anthony, F.M., Dave, R., Dube, A., Shastri, K., Kumar, Y., Prakash, N., Ranade, S., Shringarpure, R., Chapagain, D., Chaudhary, I.P., Joshi, A.K., Paudel, K., Kabir, T., Ahmed, S., Azmiri, K.Z., Cuthbert, R.J., Bowden, C.G.R., Green, R.E. 2021. Trends in the availability of the vulture-toxic drug, diclofenac, and other NSAIDs in South Asia, as revealed by covert pharmacy surveys. Bird Conservation International 31:3. VIEW

Green, R.E., Taggart, M.A., Senacha, K.R., Raghavan, B., Pain, D.J., Jhala, Y., Cuthbert, R. 2007. Rate of Decline of the Oriental White-Backed Vulture Population in India Estimated from a Survey of Diclofenac Residues in Carcasses of Ungulates. PloS ONE 2. VIEW

Prakash, V., Galligan, T.H.,, Chakraborty, S.S., Dave, R., Kulkarni, M.D., Prakash, N., Shringarpure, R.N., Ranade, S.P., Green, R.E. 2017. Recent changes in populations of Critically Endangered Gyps vultures in India. Bird Conservation International 29:1. VIEW

Swan, G., Naidoo, V., Cuthbert, R., Green, R.E., Pain, D.J., Swarup, D., Prakash, V., Taggart, M., Bekker, L., Das, D., Diekmann, J., Diekmann, M., Killian, E., Meharg, A., Patra, R.C., Saini, M., Wolter, K. 2006. Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures. PloS Biology 4:3. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: White-rumped Vulture © S Lovell.

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.