Birders love vagrants – birds that have wandered outside their normal breeding, migratory, or winter ranges to show up in a new place, often far from where they belong. What fun to be able to add a new species to one’s life, country, or patch list with a bird that may well be abundant where it normally lives but is now special. Birders are often obsessed with tracking down these vagrants – often at considerable expense (Moore 2013) – for the bragging rights.

Several reasons have been suggested to explain the existence of vagrants (Bozó & Csörgő 2024), each of them probably correct for a particular species. It has long been appreciated that most vagrants to North America and Europe come from the west, with the prevailing storms, or from the south, with migrants. But are they really becoming more and more common these days. Certainly, there would seem to be more reported every year from Alaska and the UK. This past autumn saw what appears to have been an unprecedented number of North American vagrants in the UK, including in November 2023 the first record of a Cape May Warbler in England on the Isles of Scilly.

The earliest treatises on birds and ornithology by Aldrovandi, Belon, Ray and others in the 17th and 18th centuries make no mention of what we would now call vagrants, as far as I can tell. This is not so surprising as there may have been fewer than 1000 people worldwide studying birds in those days, albeit more often with the gun than a pair of binoculars.

The Scottish parson-naturalist John Fleming [1785-1857] provides the first cataloguing of vagrants that I am aware of, in his History of British Animals (Fleming 1828). Fleming even mentions ‘occasional visitants’ in the title of his book, and distinguishes between “Periodical Visitants chiefly [that] belong to the class of Birds” and “Stragglers…irregular visitants…Driven from their native haunts to this country by some temporary calamity, the persecution of foes, or the fury of a storm…” He also includes possibly the earliest record of a vagrant from North America, a Swallow-tailed Kite killed at Ballachulish in Scotland in 1772. Dr John Walker [1731-1803] had written this in his personal diary, called ‘Aversaria’ now archived the Special Collections Department of the University of Glasgow. This kite is a large and striking North American bird that would have stood out from the local avifauna of western Scotland.

Then, in his History of British Birds, William Yarrell [1784-1856] summarized 40 examples of vagrants of some 20 North American species that had been recorded in Europe. He notes that most were found in the UK, but very few in Germany, France, and The Netherlands, reflecting the presumed typical movement of vagrants from west to east (Yarrell 1845). Yarrell called the occurrence of such vagrants “an interesting problem, with difficult solution” (quoted in Gätke 1860) as he could not fathom how a small bird could possibly cross the broad, inhospitable expanse of the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 1. Heinrich Gätke (Gätke 1895).

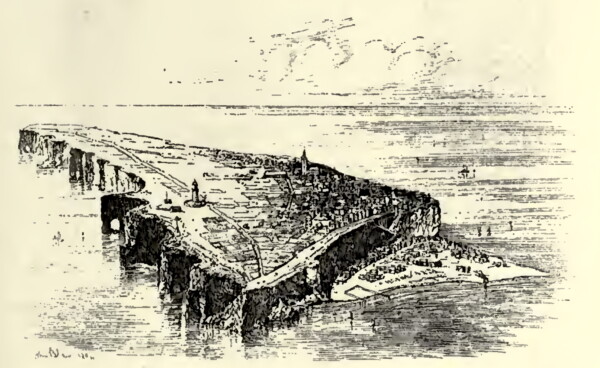

The fabulously hirsute Heinrich Gätke [1814-1897] took up that challenge and deduced that such ocean crossings would be physically possible based on his estimates of flight speeds, distance travelled, and the endurance of a migratory bird. Though he came to the right conclusion, his estimates of flight speeds and stamina were far off the mark. Gätke’s interest in vagrants was fuelled by encountering 10 species far from their normal ranges—2 from Africa and 4 each from North America and far eastern Asia—during the first 19 years that he lived on Heligoland. Heligoland is a small archipelago in the North Sea off the northwest coast of Gätke’s native Germany and was to become, in 1891, the site of a justly famous bird observatory established by Gätke.

The establishment of bird observatories and the more-ready availability of binoculars and cameras in the 1900s certainly resulted in more vagrants being documented. Thus, it seems very likely that the increased numbers of vagrants reported in recent decades is the result of the post-war boom in birdwatching and the ease of travel to remote locales. There are now reckoned to be about 45 million birders in North America and 3 million in the UK. But the numbers of vagrants does depend on factors like the weather, the climate and the available habitat, all of which are now changing at an alarming rate. Birders might be delighted at the resulting increase in rarities but any well documented increase in the number of birds that seem to have lost their way might be yet another warning sign about the uncertain future of our natural environment.

Figure 2. Heligoland (Gätke 1895).

Further Reading

Bozó, L., Csörgő, T. 2024. Causes of vagrancy of North Asian passerines in western Europe. IBIS 166. VIEW

Fleming, J. 1828. A History of British Animals, exhibiting the descriptive characters and systematical arrangement of the genera and species of quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, fishes, mollusca, and radiata of the United Kingdom, including the indigenous, extirpated, and extinct kinds, together with periodical and occasional visitants. Bell & Bradfute:Edinburgh pp.565.

Gätke. H. 1860. On the occurrence of American birds in Europe. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 26.

Gätke, H. 1895. Heligoland as an ornithological observatory: the result of fifty years’ experience [translated from the German by R. Rodenstock]. David Douglas:Edinburgh.

Moore, D. 2013. Birds: Coping with an Obsession. New Holland:London.

Yarell, W. 1845. A History of British Birds. John van Voorst:London

Image credits

Top right: Cape May Warbler | CC BY-SA 4.0 Rhododendrites Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here