LINKED PAPER Sex-biased dispersal in the Arabian babbler. Ostreiher, R., Mundry, R., & Heifetz, A. (2025) IBIS (Early View).VIEW

The Arabian Babbler

The Arabian Babbler (Argya squamiceps) is a cooperative songbird inhabiting desert streambeds along the Rift Valley, from the Arabian Peninsula north to Israel. Unlike most birds that breed in pairs and live alone or in flocks outside the breeding season, babblers form stable, year-round groups of two to twenty-five individuals of both sexes and of mixed ages. These territorial groups depend on cooperation: members defend their territory together, share resources, and maintain a hierarchy, where dominants have priority access to food and breeding (Zahavi, 1990).

Males are about ten percent larger than females and may show mild aggression while foraging, though serious fights are rare and can sometimes end with the expulsion or even death of the loser. Babblers strictly avoid inbreeding: individuals never mate with those they grew up with, even if genetically unrelated. Therefore, in order to breed, sexually mature individuals need either to disperse into another group, or to wait until an emigrant of the opposite sex joins their current group (Ostreiher et al., 2022). Group composition therefore changes over time through mortality, recruitment, and dispersal.

Figure 1. A babbler in a sentinel position.

Figure 1. A babbler in a sentinel position.

All members, including non-breeders and juveniles, help raise the young – incubating, feeding, and protecting nestlings and fledglings (Ostreiher, 1997). This cooperative breeding, unusual among birds, challenges the Darwinian view that evolution favours only individual success. Among Israel’s ~580 bird species, the Arabian Babbler is probably the only one living permanently in cooperative groups.

The Long-Term Research Project

Research on Arabian Babblers began in 1971 with Prof. Amotz Zahavi (Zahavi, 1990) and continues today in Israel’s southern Arava Desert. The study area is saturated with babbler territories, and during the study period, included about 40 territorial groups of 2–26 individuals each. Researchers and volunteers from Israel and abroad have participated for decades. The project explores ecological and social mechanisms promoting cooperation and mutual aid in a harsh desert where competition for resources is intense.

Figure 2. A ten days old nestling after ringing.

Figure 2. A ten days old nestling after ringing.

Nestlings are ringed at ten days old, just before fledging, and each bird carries a unique combination of four coloured rings for identification. Because the birds are habituated to human presence, they can be observed from one or two metres without disturbance. Groups are visited up to twice a week, depending on research goals. Most data come from observations, occasionally supported by experiments.

A Group-Living Bird’s Dilemma

In babbler societies where inbreeding is avoided, mature individuals face a key decision: stay home or leave (Heifetz, 2023). Over 17 years, we tracked hundreds of colour-ringed birds in the research area to understand how males and females differ in dispersal timing and behaviour.

Following Dispersal Events

Since 1971, we have documented 378 dispersal events, mostly by subordinate young adults unable to breed in their natal groups. In 43 events involving 91 females and in 21 events involving 65 males, we observed the departure itself and stayed in the desert with the dispersers from dawn to dusk, learning the process of each dispersal event from its beginning to its end.

Encounters always occurred inside resident territories, where newcomers were intruders. Of the 64 events, four failed and the participants perished; in the remaining 60, integration succeeded. First contact was always initiated by dispersers, typically after staying quietly in the territory for at least five hours, sometimes up to two and a half days, before initiating contact.

In 23 cases, integration was peaceful, usually after the disappearance of a dominant of the same sex. Dispersers advanced slowly, stopped near a subordinate resident, and began autopreening with soft, quiet calls (self-directed preening for feather care and social signalling); the resident also responded by autopreening. They approached each other, and autopreening gradually turned into allopreening (preening directed toward another bird, serving maintenance and social functions). Sometimes these acts involved additional residents. The interactions lasted less than ten minutes, after which the newcomer or newcomers foraged calmly with the group.

Figure 3. Arabian Babblers allopreening.

Figure 3. Arabian Babblers allopreening.

In 37 other cases, integration involved aggression: residents attacked first, dispersers retreated, but returned repeatedly. In many cases, the balance eventually reversed, with the disperser attacking and expelling the dominant resident. These confrontations could last for hours or even days.

Results and Interpretation

Using 17 years of data covering 64 events and 156 individuals, we compared females and males in seven traits: (1) age at dispersal, (2) coalition size, (3) likelihood of dispersing alone, (4) distance moved, (5) transience duration, (6) aggression upon joining, and (7) natal group size.

The species shows strong male philopatry; males usually remain in or near their natal group, while females disperse more often, sometimes alone or in small coalitions of sisters, and often to more distant groups. No sex difference appeared in transience duration or aggression during integration.

These findings suggest that females face stronger pressures to leave, likely due to limited breeding opportunities and lower social status. Although dispersal costs were not measured directly, females probably bear higher risks and energy demands. A feedback dynamic may occur: female-biased dispersal reinforces male philopatry, amplifying sex differences.

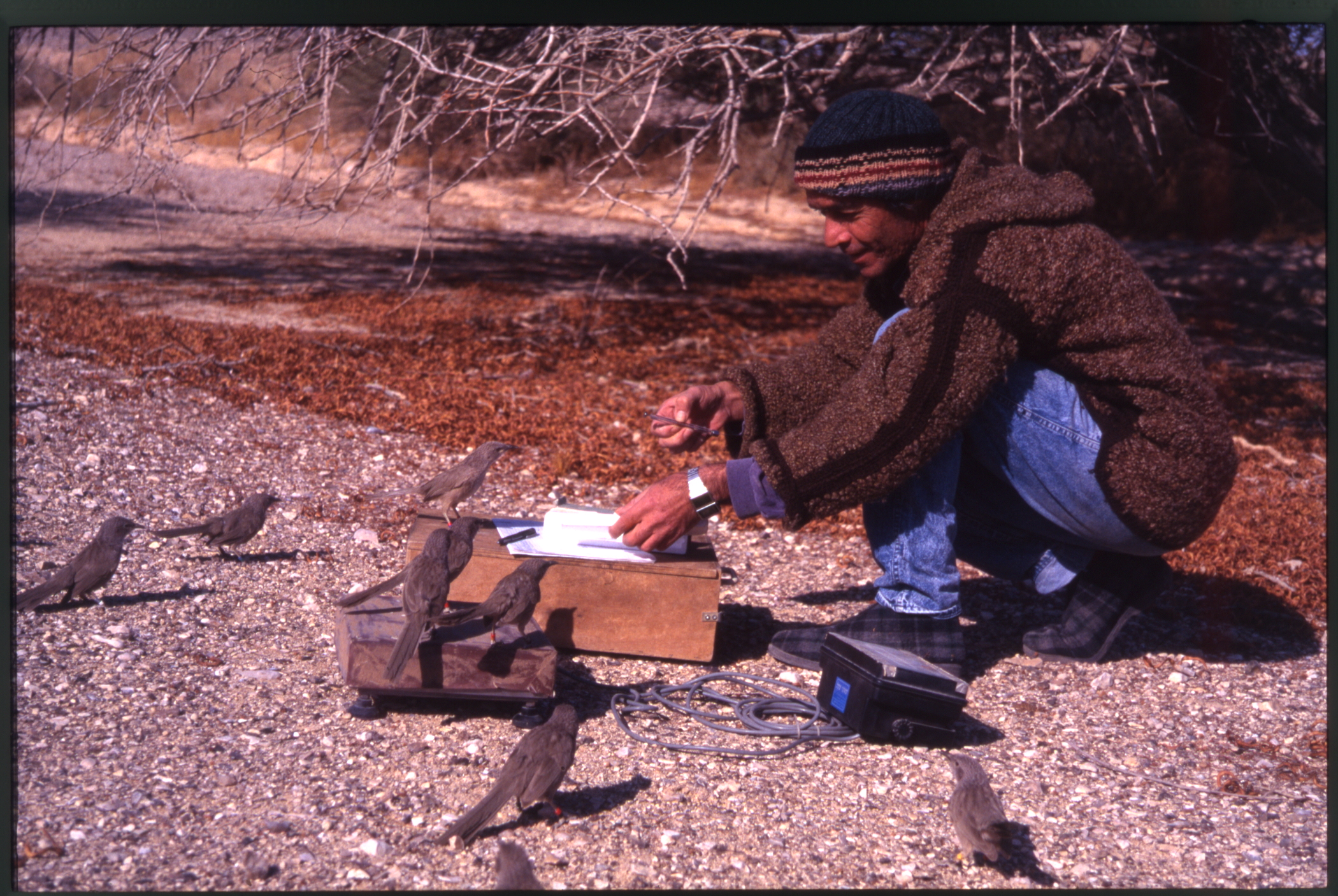

Figure 4. Conducting fieldwork by Arabian Babbler flock.

Figure 4. Conducting fieldwork by Arabian Babbler flock.

Why Do Females Leave?

Female-biased dispersal likely reflects restricted breeding opportunities and subordinate status at home. By leaving, females improve their breeding prospects, whereas males gain by staying: waiting safely for opportunities, maintaining social bonds, and helping relatives. This pattern stabilizes babbler social structure and illustrates how cooperation and competition co-evolve in social animals.

Overall, our study reveals close links between social organisation, reproductive constraints, and sex-specific dispersal strategies, underscoring the value of long-term, individual-based research for understanding the evolution of cooperation.

Figure 5. Babbler in flight.

Figure 5. Babbler in flight.

References

Heifetz, A. 2023. The disperser dilemma in cooperatively breeding birds. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 36(10):1539-1546.VIEW

Ostreiher, R. 1997. Food division in the Arabian babbler nest: adult choice or nestling competition? Behavioral Ecology 8:233-238.VIEW

Ostreiher, R., Mundry, R. and Heifetz, A. 2022. Actual versus counterfactual fitness consequences of dispersal decisions in a cooperative breeder. Ethology Ecology & Evolution 35(4):408-423.VIEW

Zahavi, A. 1990. Arabian babbler: the quest for social status in a cooperative breeder. In: Stacey, P.B. & Koenig, W.D. (eds.), Cooperative Breeding in Birds. Cambridge University Press, London, 103–130.

Image credit

All images were taken by © Roni Ostreiher.