LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Using web-sourced photographs to examine temporal patterns in sex-specific diet of a highly sexually dimorphic raptor. Panter, C.T. & Amar, A. 2022 Royal Society Open Science. doi: 10.1098/rsos.220779 VIEW

Knowledge of animal diets is essential to understand a species’ ecology and resource requirements through time and space. Information on what a species feeds on provides a foundation for better understanding of species interactions between one another, energy flows through food webs and the structuring of ecological communities – which is vital for conservation management and wider ecological research.

Many birds exhibit diet differences between the sexes, this is most pronounced in predatory birds such as raptors. Raptors are a fascinating group with many species displaying reversed sexual size dimorphism, i.e., the female is the larger of the two sexes. The degree of sexual dimorphism in raptors is strongly linked to diet, with bird-eating raptors such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) showing the greatest size differences between the sexes.

There are many evolutionary hypotheses that attempt to explain reversed sexual dimorphism in raptors, e.g., the ‘intersexual competition’ hypothesis (in short, the two sexes feed on different dietary niches during the breeding season to avoid competing with one another) (Krüger 2005). In fact, such hypotheses are often difficult to prove and approximately 20 hypotheses attempting to explain reversed sexual dimorphism in raptors now exist. However, what we know for sure is that intersexual size differences are often reflected in what raptors eat.

Studying raptor diets is tricky. Methods used, such as analysis of prey remains, pellets, hide watches and more recently nest cameras, often do not allow for between-sex dietary differences to be ascertained and, without arduous fieldwork, do not allow for the study of raptor diets across the entire year.

What if there was a way to study raptor diet throughout the year, between the sexes and at the wider population level?

iEcology and web-sourced photography

Thanks to the increasing popularity of citizen science, iEcology, i.e., “the quantification of patterns and processes in the natural world using data accumulated in digital sources” (Jarić et al. 2020) and more specifically the analysis of web-sourced photographs, allows for just this.

In our latest study published in Royal Society Open Science, we use web-sourced photographs of Eurasian Sparrowhawk on kills taken throughout the United Kingdom, and explored dietary differences between the sexes across the entire year. Recently, this approach has been used to explore geographic- and demographic- differences in raptor diets (see Naude et al. 2019; Panter & Amar 2021), however, temporal dietary patterns have yet been explored.

We used a Google Images API called ‘MORPHIC’, which was developed by Leighton et al. (2016), and examined 666 photographs of sparrowhawk on prey. We manually identified sparrowhawk sex and individual prey species for each photograph. In addition, manual searches were conducted on websites not accessed by MORHPIC including Facebook, Twitter and BirdGuides.

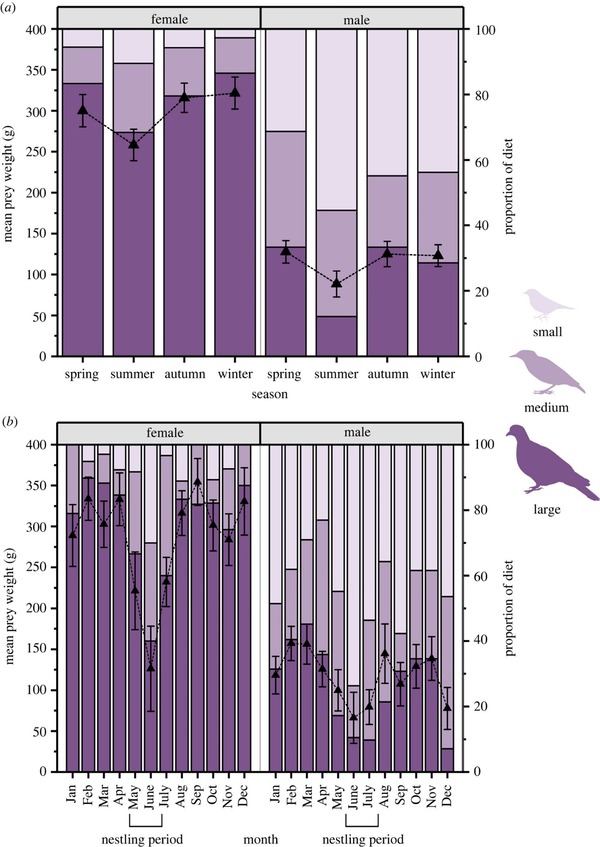

Assigning mean prey weights to each prey species, we found that prey weight was higher for female sparrowhawk across the year – not surprising given what we know about reversed sexual dimorphism in bird-eating raptors. However, on average, prey weight for both sexes declined during the summer period between May and June. In fact, mean prey weight was lowest in June which is the main nestling-rearing month for both sparrowhawks and their prey.

Figure 1 Prey weights (g) and proportion of different prey size classes (small, medium and large) within the diet of adult male and female Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) in the United Kingdom (a) across seasons and (b) by month. Error bars = standard error.

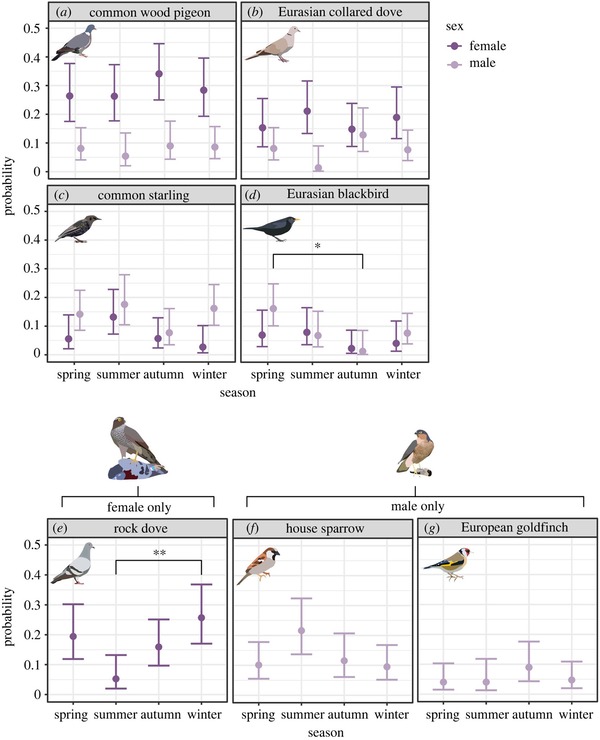

We also explored seasonal differences in key prey species, i.e., those that represent ≥5% of sparrowhawk diet, with Feral Pigeons (Columba livia) being more important for female sparrowhawk in summer compared to winter. Whereas for males, Common Blackbird (Turdus merula) were more important in spring compared with autumn.

Figure 2 Seasonal patterns in probabilities of key prey species in the diet of adult Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) in the United Kingdom: (a) Common Wood Pigeon (Columba palumbus), (b) Eurasian Dollared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto), (c) Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), (d) Eurasian Blackbird (Turdus merula), (e) Rock Dove (Columba livia), (f) House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and (g) European Goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis). Statistical significance thresholds: ‘**’ = p < 0.01 and ‘*’ = p < 0.05. Error bars = 95% confidence intervals.

This is the first time that raptor diets have been explored, at the wider population level, throughout the entire year. Our approach allowed us to examine demographic differences in Eurasian Sparrowhawk diet without the need for time-consuming fieldwork.

That being said, fieldwork and traditional methods to study raptor diets are immensely valuable to science, providing high-resolution dietary data at the pair- and individual-levels. Data from the field is still better used when testing evolutionary hypothesises, such as the ‘intersexual competition’ hypothesis. This is because web-sourced photographs do not allow for inferences to be made from specific birds, therefore, we have no knowledge about individual brood rearing status or reproductive success rates.

Accessible to all

However, for broad scale patterns to be observed, our new approach provides a rapid method to explore intersexual diet differences in raptors and can be applied to any well-sampled species; beyond birds.

Web-sourced photography is a new method that remains accessible to researchers without access to large funds or those from regions where fieldwork is not an option. The only requirements include access to a reliable internet connection and experience identifying predator and prey species.

If you would like to learn more about our raptor research using web-sourced photography or would like to discuss a research idea, please do get in touch – we’d like to hear from you!

References

Jarić, I. et al. 2020. . iEcology: harnessing large online resources to generate ecological insights. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 35:630-639. VIEW

Krüger, O. 2005. The evolution of reversed sexual size dimorphism in hawks, falcons and owls: a comparative study. Evolutionary Ecology 19:467-486. VIEW

Leighton, G.R.M., Hugo, P.S., Roulin, A. and Amar, A. 2016. Just Google it: assessing the use of Google Images to describe geographical variation in visible traits of organisms. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7:1060-1070. VIEW

Naude, V.N., Smyth, L.K., Weideman, E.A., Krochuk, B.A. and Amar, A. 2019. Using web-sourced photography to explore the diet of a declining African raptor, the Martial Eagle (Polemaetus bellicosus). The Condor 121:duy015. VIEW

Panter, C.T. and Amar, A. 2021. Sex and age differences in the diet of Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) using web-sourced photographs: exploring the feasibility of a new citizen science approach. Ibis 163:928-947. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: © Imran Shah CC BY 2.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.