LINKED PAPER  Repopulation of the former breeding range: spatio-temporal patterns and drivers of reproduction in the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) population in Hungary. Prommer, M., Bagyura, J., Kéry, M. & Oli, M. K. 2025. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13448 VIEW

Repopulation of the former breeding range: spatio-temporal patterns and drivers of reproduction in the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) population in Hungary. Prommer, M., Bagyura, J., Kéry, M. & Oli, M. K. 2025. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13448 VIEW

Three decades of absence

The Peregrine Falcon is renowned as the fastest animal on Earth, capable of reaching speeds of over 300 km/h in a hunting dive. Its remarkable abilities have long been admired by people and were even harnessed for hunting. In Hungary, the ancient tradition of falconry provides evidence, through historical records from the 13th century, along with stairways carved into cliffs leading to peregrine nests, for the species’ past presence as a breeder in the country. However, by 1964, widespread pesticide use had wiped out the breeding population, leaving the species absent for more than three decades.

In the 1980s, when I attended elementary school, it seemed impossible that the peregrine, my favourite bird species, would ever breed in Hungary again. I collected all the available information about the species, which was very limited in Hungary at that time, and tried to visit sites where I thought I would have the highest chance to see a peregrine. Usually, I failed. Then in the early 1990s, sightings became more frequent, as the European population started to recover.

Finally, in 1997, peregrines returned — naturally, without any reintroduction programme — and their comeback since then offers valuable insights into how species can recover, adapt, and persist in changing landscapes.

Tracking a comeback

Since 1997, researchers, national park rangers, and volunteers from MME–BirdLife Hungary have tracked the falcon’s recovery. Because Hungary lacks high mountains and towering cliffs, nearly all peregrine nesting sites are relatively easy to reach. As a result, the monitoring programme is able to cover around 90% of known territories each year, while also surveying potential but as yet unoccupied sites—making it one of the most comprehensive raptor datasets in Central Europe.

Figure 1. The author inspects and rings nestlings. © Bence Krajcsovszky

Figure 1. The author inspects and rings nestlings. © Bence Krajcsovszky

The results show a strikingly strong return: from just two occupied sites in 1997, the population grew to over 120 pairs by 2022. Around 71% of nesting attempts were successful, with falcon pairs typically raising 2–3 chicks. These figures match global averages — a sign that Hungary’s peregrines are thriving.

First the mountains, then the plains

The recovery followed a clear pattern. Peregrines first returned to their traditional haunts — cliffs and quarries in forested, mountainous regions. As the population expanded, they pushed into lower agricultural landscapes with few or no cliffs, places where the species had never bred before. There, they embraced a thoroughly modern substitute: nest boxes mounted on electricity pylons. These boxes had originally been placed for the endangered Saker Falcon, but peregrines eagerly adopted them. Surprisingly, they were even more successful (91%) there than on natural cliffs (62%).

Weather, habitat, and regional differences

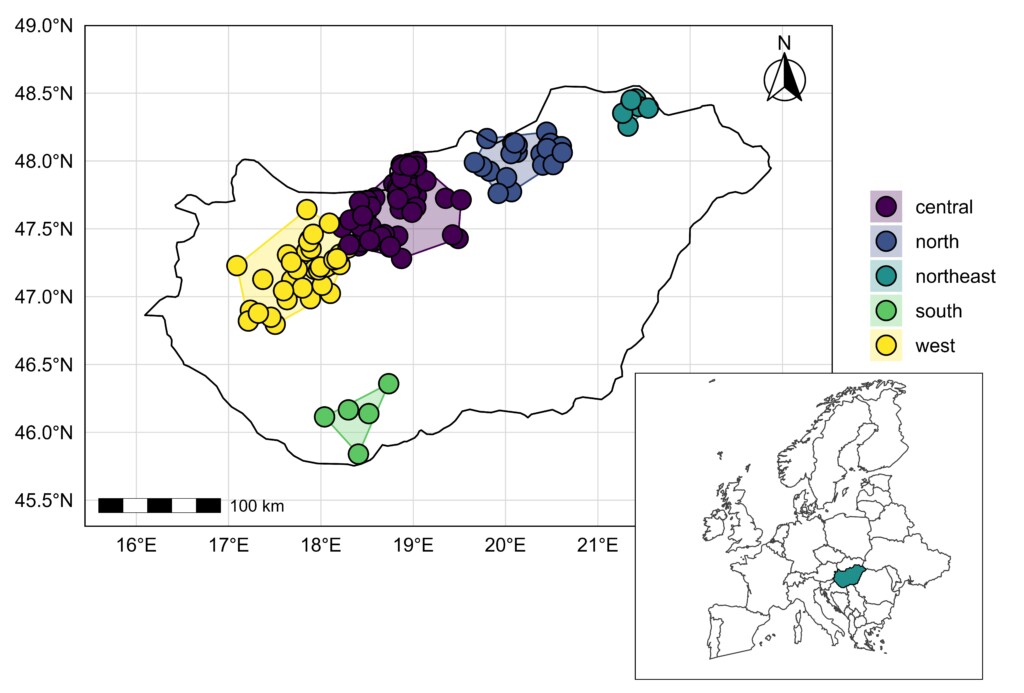

Not all territories, however, are equal. By grouping breeding pairs into five regional clusters, the study showed that peregrine success is far from uniform. Breeding outcomes differ markedly across Hungary’s regions — a striking finding given that the country, at 93,000 km² (about the size of Portugal or the US state of Indiana), supports peregrines in only a third of its area.

Figure 3. Geographical groups of breeding pairs in Hungary: western (white circles), central (blue), north (periwinkle), and south (light blue) clusters.

Figure 3. Geographical groups of breeding pairs in Hungary: western (white circles), central (blue), north (periwinkle), and south (light blue) clusters.

- Southern pairs raised the most chicks, averaging three per successful nest.

- Northeastern pairs fared worst, producing smaller broods — possibly due to growing pressure from Eagle Owls, a powerful predator and competitor.

- In the wet western region, elevated total rainfall in March reduced brood sizes, echoing findings from other countries that wet nests and prey shortages can kill chicks.

- Also in the west, an unexpected pattern emerged: higher ‘greenness’ in February — essentially an early spring — actually reduced nesting success. The most likely explanation is a mismatch with prey availability. In milder years, small birds begin breeding earlier, which means that by the time Peregrines are mating and laying eggs, many potential avian prey are already incubating their nests and are therefore out of reach. As a result, the male, which relies on catching smaller birds to feed the female during this critical period, finds fewer accessible prey — just when the pair need them most.

These findings highlight those local conditions — climate, habitat, access to prey, and pressure from other predators — all shape the recovery process.

Lessons for conservation

The peregrine’s return is a global conservation success story. It proves that banning harmful chemicals and protecting habitats can bring even heavily depleted species back from the brink. Yet our study also shows that recovery is not uniform: regional and fine-scale differences shape breeding outcomes, meaning that conservation strategies must be tailored to local conditions.

The comeback also brings fresh challenges. In some regions, peregrines face growing pressure from the Eurasian Eagle Owl — an apex predator, itself recovering from near-extinction and also legally protected. At the same time, perhaps partly in response to this pressure, peregrines have spread into lowland areas where they had never bred before, readily occupying artificial nest boxes. Yet these boxes were originally installed for the endangered Saker Falcon, which now relies on them. If peregrines continue to expand and competition for these man-made sites intensifies, conservationists will face the delicate task of supporting both species without allowing one to prosper at the expense of the other.

Figure 4. Adult female Peregrine Falcon perching at an artificial nest box on a high-voltage transmission line tower. © Mátyás Prommer

Figure 4. Adult female Peregrine Falcon perching at an artificial nest box on a high-voltage transmission line tower. © Mátyás Prommer

A falcon’s second chance

Hungary’s peregrines are now firmly re-established. Their journey from extinction to expansion — from cliffs to pylons — offers hope, but also a reminder that recovery is complex. As climate change, land use, and species interactions continue to shift, ongoing monitoring and adaptive conservation will be vital.

Once wiped out by human actions, peregrines now soar again over Hungary. Their story proves that with persistence, science, and a bit of ingenuity, even dramatic declines can be reversed.

LISTEN to an AI-generated podcast, generated by the author, discussing the paper.

References

Prommer, M. & Bagyura, J. 2018. Review of the development of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) population in Hungary between 1997 and 2018. Ornis Hungarica, 26: 2-11.

Carlzon, L., Karlsson, A., Falk, K., Liess, A. & Møller S. 2018. Extreme weather affects Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus tundrius) breeding success in South Greenland. Ornis Hungarica, 26: 38-50.

Beran, V., Vrána, J. & Horal, D. 2018. Population trends and diversification of breeding habitats of Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) in the Czech Republic since 1990. Ornis Hungarica, 26: 121-129.

Lindner, M. 2018. Influence of the Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo) on the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) population in Germany. Ornis Hungarica, 26: 243-253.

McGrady, M.J., Hines, J.E., Rollie, C.J., Smith, G.D., Morton, E.R., Moore, J.F. Mearns, R.M., Newton, I., Murillo-García, O.E., & Oli, M.K. 2017. Territory occupancy and breeding success of Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus at various stages of population recovery. Ibis, 159: 285-296.

Fidlóczky, J., Bagyura, J., Nagy, K., Szitta, T., Haraszthy, L. & Tóth, P. 2014. Bird conservation on electric-power lines in Hungary: Nest boxes for saker falcon and avian protection against electrocutions. Projects’ report. Raptor Journal, 8

McGrady, M.J., Hines, J.E., Rollie, C.J., Smith, G.D., Morton, E.R., Moore, J.F. Mearns, R.M., Newton, I., Murillo-García, O.E., & Oli, M.K. 2017. Territory occupancy and breeding success of Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus at various stages of population recovery. Ibis, 159: 285-296.

Image credit

Top right: Adult female Peregrine Falcon above her nest. © Mátyás Prommer