Unexpected breeding dispersal behavior in the Grasshopper Sparrow

LINKED PAPER

Patterns and correlates of within-season breeding dispersal: A common strategy in a declining grassland songbird. Williams, E.J. & Boyle, W.A. 2018. The Auk. DOI: 10.1642/AUK-17-69.1. VIEW

To the untrained eye, a Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum, is a hard sell. When there are manakins that moonwalk, crows that use tools, and parrots that can form full, intelligible sentences, Grasshopper Sparrows are just another little brown job, right?!

It is understandable why Grasshopper Sparrows join the ranks of other birds commonly referred to as “LBJs.” Except for the flash of yellow near their eyes and at the top of their wings, Grasshopper Sparrows are largely brown all over. A quiet, cryptic, small bird, they spend most of their time on the ground. Except for a few months of the year during the breeding season, when males conspicuously perch on top of fence posts and sing to defend territories, Grasshopper Sparrows can be incredibly difficult to detect, let alone know they’re even around. Even their territorial song is unassuming and arguably inconsequential; the breadth of their melodious repertoire covers a high-pitched, insect-like “buzzzzzz!” that is over before the binoculars are even up.

While all of these traits would classify them as a little brown job, such characteristics have their advantages. Being small means Grasshopper Sparrows are usually not alimentary fodder for larger predators that want more bang for their buck. Being brown and otherwise unflamboyant also helps with avoiding predation. Moreover, spending so much time on the ground is great for finding plump, protein-rich insects that are a staple of Grasshopper Sparrow diet.

While Grasshopper Sparrows admittedly may be little brown jobs, a little known fact is that they are masters of movement. Following three seasons at the Konza Prairie Biological Station in eastern Kansas, USA, our team discovered a phenomenon not currently documented in the life history of Grasshopper Sparrows. Using a mixed bag of field techniques and the help of a large field crew, we recorded within-season breeding dispersal occurring in a Great Plains population of Grasshopper Sparrows.

Within-season breeding dispersal, or the one-way movement between breeding attempts within a single breeding season, is thought to be an uncommon behavior among birds. While breeding dispersal – the movement between breeding attempts among years – has been well documented in a suite of avian taxa, the “norm” for birds during the breeding season, however, is to select a territory and stay put. The time and energy it requires to find and defend a territory, select a mate, build a nest, and produce young is usually more than enough for temperate-breeding birds, who also have a limited 2-4 month time window in which to complete all of these activities. The possibility of having to do all of that twice or more doesn’t seem like it would be worth it. The fact that Grasshopper Sparrows are doing this once, twice, three times, even – makes them all the more unusual.

Within-season breeding dispersal in Grasshopper Sparrows: how often does it happen? When does it happen? Where do they go? Why do they do it? We set out to answer all of these questions. Using radio tracking, mist-netting to capture birds, and weekly surveys to re-sight marked individuals, we made direct observations of movements, noted territory turnover, and measured density of individuals on study plots. By these metrics, we were able to record the frequency, distances, and locations of movements over three breeding seasons. What we discovered was surprising.

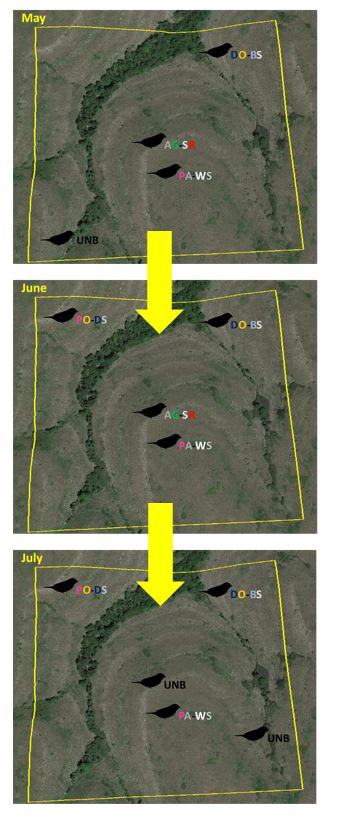

Figure 3 This graphic gives an example of how territory turnover occurs in one of the Konza study plots over the breeding season. Each panel represents a Google Earth image of a single plot through the months of the breeding season, May – July (upper left corner of panel). Each sparrow silhouette represents a banded bird (denoted by the 4-letter color code) or an unbanded bird (denoted by “UNB”). In May, there are 3 banded birds and 1 unbanded bird. From May to June, the unbanded bird leaves the plot, and a new bird, PO-DS, comes in. From June to July, a banded bird, AG-SR, is replaced by an unbanded bird, and a new unbanded bird has entered the plot

Figure 3 This graphic gives an example of how territory turnover occurs in one of the Konza study plots over the breeding season. Each panel represents a Google Earth image of a single plot through the months of the breeding season, May – July (upper left corner of panel). Each sparrow silhouette represents a banded bird (denoted by the 4-letter color code) or an unbanded bird (denoted by “UNB”). In May, there are 3 banded birds and 1 unbanded bird. From May to June, the unbanded bird leaves the plot, and a new bird, PO-DS, comes in. From June to July, a banded bird, AG-SR, is replaced by an unbanded bird, and a new unbanded bird has entered the plot

Intensive survey efforts revealed striking patterns of Grasshopper Sparrow density; some areas changed dramatically over the season, and others remained fairly constant. Even within those areas of unchanging density, however, a lot of territory turnover was happening. While an individual plot may have had 5-6 territory holders on it from May to July, the individuals holding those territories were shifting. Direct observations of movements also displayed an amazing ability to cover long distances over short time spans for such a small bird. Some Grasshopper Sparrows seen defending a territory in one spot were then found just a couple of days later, singing at a territory more than 8 kilometers away.

One of the biggest surprises was just how common were the dispersal movements. With between 33-75% of individuals dispersing each season, Grasshopper Sparrows showed a remarkable propensity to move over short time scales. The prevalence of within-season breeding dispersal may indicate that Grasshopper Sparrows are more plastic in their behavior than is currently appreciated. Dispersal may be a product of making decisions based on current and past experiences on the breeding grounds.

This high mobility in Grasshopper Sparrows has important implications for how researchers study birds during the breeding season. Without exhaustively surveying the same areas for marked birds on a regular basis, researchers will underestimate how much movement is occurring over the breeding season. Further, scientists could falsely attribute disappearances of individuals to mortality, when in fact those birds may be dispersing to areas off the study site.

A more positive note from this work, however, is the importance of high mobility for conservation. Much of the preferred habitat of Grasshopper Sparrows and other similar species is continuous grassland, unfettered by agriculture, development, and woody encroachment. While continuous grassland is largely impossible in a growing, industrialized world, many habitat management programs acquire small parcels of land to restore back to grassland. A capacity for high movement, in this case, may be a good thing, as grassland birds may be able to capitalize on isolated patches of restored grassland habitat.

While our work has revealed the first part to a currently unknown and unexpected behavior of Grasshopper Sparrows, the story doesn’t end there. Forthcoming work relating to why these birds move and what shapes settlement decisions following within-season breeding dispersal is still to come.

While we may have newfound appreciation for one aspect of Grasshopper Sparrows, there may be more than the eye can see. What else might we find out about little brown jobs? Don’t let their unassuming exterior fool you. There may be a world of exciting discovery about them, just quietly waiting behind that flashy Greater Prairie Chicken, Tympanuchus cupido, booming for attention.

Further reading

American Ornithological Society. 2017. Grassland Sparrows constantly searching for a nicer home. American Ornithology Publications Blog. October 11, 2017. Available from: https://americanornithologypubsblog.org/2017/10/11/grassland-sparrows-constantly-searching-for-a-nicer-home/. VIEW

Williams, E.J. 2017. Author blog: To the Grasshopper Sparrow, the grass may be greener on the other side. American Ornithology Publications Blog. October 11, 2017. Available from: https://americanornithologypubsblog.org/2017/10/11/author-blog-to-the-grasshopper-sparrow-the-grass-may-be-greener-on-the-other-side/. VIEW

Image credit

Featured image: Grasshopper Sparrow, Ammodramus savannarum © Dave Rintoul

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.