LINKED PAPER

Prey Species in the Diet of the Amur Falcon (Falco amurensis) During Autumn Passage Stopover in Northeast India. Kaur, A., Jacob, A. Mehta, D., Kumar, S.R. 2024. Journal of Raptor Research. DOI: 10.3356/JRR-23-49 VIEW

Amur Falcons (Falco amurensis) are small raptors that engage in a transcontinental migration twice per year. Their autumn migration takes them from breeding grounds in northern Asia all the way down to southern Africa. To pull off the 3,500 km flight over the Arabian Sea (making them the raptor with the longest known flight over water), they must first stock up on protein-rich food, primarily termites. It’s estimated that one million migrating Amur Falcons can consume almost two billion termites in just over fifteen days. As insectivores, Amur Falcons are likely dependent on these termites to complete their migration, making stopover sites in north-east India a potentially critical conservation priority.

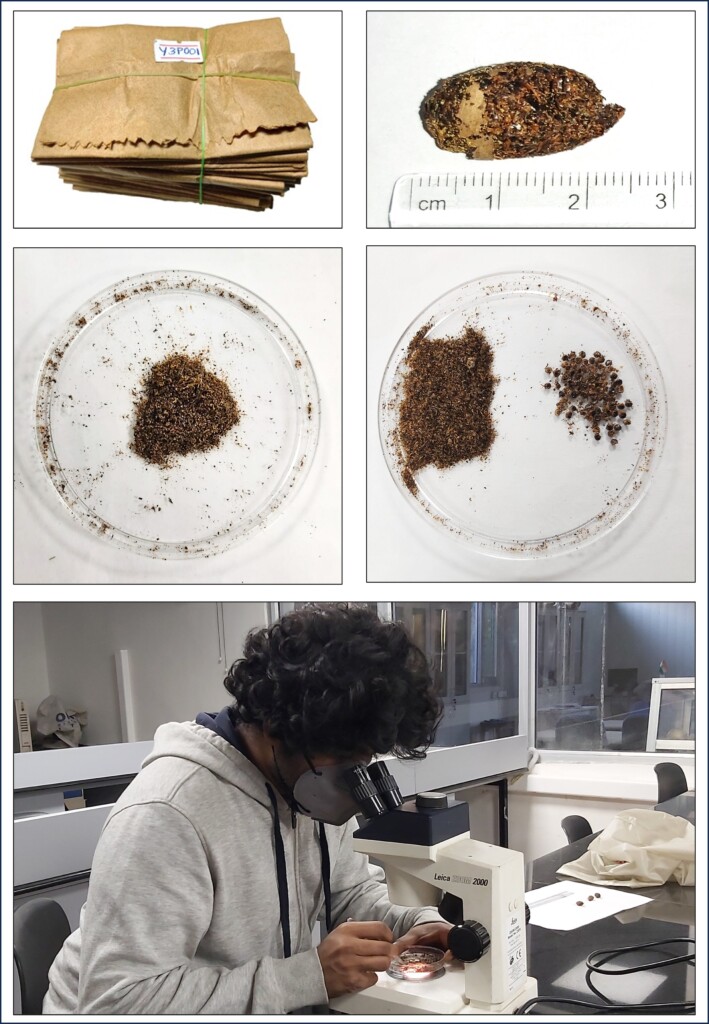

Figure 1. Lab work to determine the diet of Amur Falcons from pellets collected in Nagaland.

To determine the importance of insects in the diet of the Amur Falcon during migration, Amarjeet Kaur and her colleagues examined over 1,000 regurgitated pellets collected from beneath a prominent Amur Falcon roosting site in Nagaland, during October and November of 2017 and 2018. The pellets, which are composed of indigestible prey remains, revealed high percentages of body parts belonging to two species of fungus-growing termites, Odontotermes feae and Odontotermes horni. The termites were the most prevalent prey for the falcons across both years, and across three different roost sites. The research team also observed large numbers of Amur Falcons feeding on swarms of termites, offering further evidence that these insects are highly prized by the falcons. Termites contain an easily digestible form of protein and high levels of fat, and local hunters call Amur Falcons “loi” meaning “insect eater”. Historically hunters used to harvest falcons towards the end of their stopover season because their consumption of termites resulted in a rich layer of fat.

Today, Naga peoples are heavily involved in the protection of the falcons, and communities have shifted away from hunting Amur Falcons during the migratory period. Coauthor of the study, Suresh Kumar, initially began this project to create local awareness about the falcons, and now, he says the birds serve as a flagship species for regional conservation efforts. “Local communities in Nagaland and neighboring States of Manipur and Assam have independently begun setting aside community lands for the protection of not only Amur Falcons, but for all biodiversity in the area,” Suresh says. “Given that Nagaland is predominantly governed by community-owned land, conservation actions are significantly shaped by local residents.”

Figure 2. Swarms of termites in Nagaland, an important food source for Amur Falcons.

The findings of this study are significant because they reframe the importance of stopover sites in the annual cycles of the Amur Falcon, and particularly the pre-Arabian Sea refueling area of Nagaland. Amarjeet Kaur and her colleagues were surprised at the strength in association between the Amur Falcons and the termites, noting that “it appears that termites are the exclusive prey in this region, and the synchronisation between termite emergence and the presence of Amur Falcons is remarkable.” As long-distance migrants the falcons are tied to a tight schedule and therefore, they are potentially vulnerable to environmental change that could create a phenological mismatch in this termite-falcon synchronisation. Climate change has already affected the behaviour of other long-distance migrants such as Great Knots (Calidris tenuirostris) and Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa lapponica). This study also highlights the contribution that insectivorous raptors like the Amur Falcon in regulating insect populations, further verified by studies of the falcons on their wintering grounds in southern Africa.

Amarjeet and her colleagues hope to identify habitat-specific features of the falcon stopover sites across north-east India and use that data to develop “a more robust GIS-based modeling approach”. They also want to conduct a detailed study of how termites vary across the different sites. “We need to determine if the termite swarming events are cyclic in nature and how they might be influenced by climatic factors, particularly monsoonal rains”. If Amur Falcons rely on just a few places to acquire the energy necessary to complete their migration, then understanding site connectivity is essential and Amur Falcon conservation requires a landscape-scale approach.

Image credits

Top right: An Amur Falcon Falco amurensis catching a termite.

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here