In the early 2000s, when we were putting together a book on the modern history of ornithology, we titled it Ten Thousand Birds to reflect what seemed to be the more-or-less final tally of the number of extant bird species on earth. That number had steadily increased since Linnaeus’s definitive 10th edition of Systema Naturae in 1758 had formally described 931 bird species with scientific binomials. By 2010, the number of bird species newly discovered in remote jungles and mountains had dwindled to about one per year and there appeared to be a fairly stable balance between lumping and splitting species to make the grand total about 10,000.

We lamented, however, that a future edition of our book might have to be called ‘Nine Thousand Birds’ to reflect the catastrophic, ongoing decimation of bird populations worldwide due to climate change, pollutants, and habitat loss…in short, people. We could hardly have been more wrong, as the latest checklist of the birds of the world (AviList) recognizes 11,131 species. What happened? The short answer is: DNA and changing concepts about what constitutes a species.

To look at the shifting landscape of avian taxonomy since Linnaeus, I will use the hummingbirds as an example. The hummingbirds are a large family (Trochilidae) that occurs only in the Americas, so we can be reasonable sure when the first species were documented.

There can be no doubt that native Americans knew hummingbirds and could probably distinguish among at least a few species in their local environments. Even in the species-rich tropics, most hummingbird communities comprise fewer than a dozen species at any one site so it is unlikely that more than a few dozen species were distinguished by the indigenous peoples.

The first mention of hummingbirds in print was probably in Jean de Léry’s (1578) account of his explorations on the coast of Brazil in 1557: “But for a singular wonder, and a masterwork of miniature, there is one that I must not omit, which the savages call gonambuch, of whitish and shining plumage; although its body is no bigger than that of a hornet or a horned beetle, it excels in singing. This tiny bird, which hardly ever leaves its perch on that coarse millet that our Americans call avati, or on other tall plants, always has its beak and throat open; if you didn’t hear it and see it by experience, you would never believe that from such a little body could come a song so free and high, so clear and pure as to equal that of the nightingale.” [translation from the French by Whatley 1990]. While it might be impossible to know for sure which species he saw, the Minute Hermit (Phaethornis idaliae) is a likely candidate as it is a tiny (2 g), whitish, singing hummingbird that occurs in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil.

Then, in 1648, Georg Marcgrave [1610-1644] described 9 hummingbird species—Guainumbi, he called them in his Historia Naturalis Brasiliae—based on his discoveries in Brazil in 1638. Marcgrave illustrated one of those species but I cannot be certain about its identity but in 1743, George Edwards identified four of them in his History of Uncommon Birds based on Marcgrave’s descriptions. Edwards had used specimens in the cabinets of his colleagues in England to describe 9 and illustrate 7 hummingbirds in total.

The 10th edition of Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1758) is considered to be the foundation of modern zoological nomenclature, where each species is clearly described and given a scientific (Latin) binomial. In that edition he described and formally named 18 hummingbirds, though one of those, Trochilus afer must have been a sunbird as the specimen was from Ethiopia. Of the remaining 17 species, 9 were the same as those described by Edwards. In the 12th edition (1766) Linnaeus increased that number to 24, and in the 13th edition (in 1788 by Johann Friedrich Gmelin after Linnaeus’s death) the number was 30.

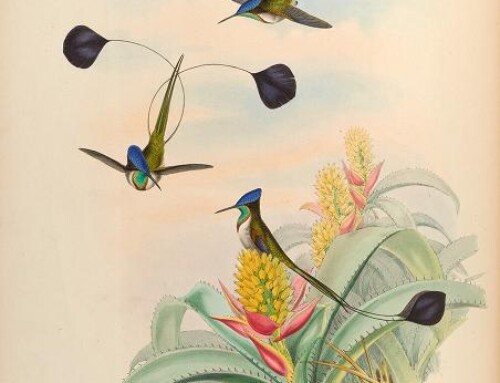

By the early 1800s, there was an explosion of European interest in hummingbirds with thousands being brought to the UK in particular, to fill cabinets of curiosity, museum drawers, and aviaries. As a result at least five major monographs on the hummingbirds were published in the 19th century, two in the UK and three in France. The first of these, published in 1802 by J.B. Audebert and L. P. Viellot, listed and illustrated only 14 species. Then in 1829, René-Primevère Lesson [1794-1849] listed 64 species in his Histoire naturelle des oiseaux-mouches, illustrating them, as well as a few nests and anatomical features, in 85 coloured engravings. At about the same time, Sir William Jardine listed 91 species in his two volume, Natural History of Hummingbirds (1833). In that monograph 62 of those species were beautifully engraved by William Lizars from watercolours by James Hope Stewart [1789-1856]. Jardine’s book was wildly successful, described by one reviewer as “one of the most beautiful Books which ever issued from the press.”

Then, from 1849 to 1861, John Gould published what is widely considered to be his masterwork, A Monograph of the Trochilidae, or Family of Humming-birds, arguably the most lavish book about a family of birds ever published. In it, 418 species are listed (with another added in a supplement published in 1889 after Gould’s death), beautifully illustrated and lithographed by Gould, Henry Constantine Richter, and William Matthew Hart. Gould’s complete monograph represents the largest number of hummingbird species ever described, in part because Gould was a splitter and sometimes identified the sexes as different species. Even Mulsant and Verreaux’s monograph, Histoire naturelle des oiseaux-mouches, ou, Colibris constituant la famille des trochilidés published in 1874 described only 117.

The Peters Checklist of the Birds of the World, which began publication in 1931, was the first of several world lists to be published during the past 100 years. Peters’s volume 5 (1945) listed 320 hummingbird species, followed by successive world lists by different authors with 330 (in 1980), 338 (in 2008), 363 (in 2015), and 370 (today). Since 1860, no hummingbird species has become extinct, so the changes in numbers are the result of both discoveries and species definitions.

The two most recently identified hummingbirds illustrate the two kinds of discovery that add species to the list. The most recently discovered species in the wild was the Blue-throated Hillstar (Oreotrochilus cyanolaemus) found in 2017 occupying a tiny range on the remote Cerro de Arcos in Ecuador. The most recently discovered species in the lab is the Northern Giant Hummingbird (Patagonia chaski) where DNA analysis showed that the former Giant Hummingbird (Patagonia gigas) is really two species that do not interbreed where their Andean ranges overlap.

While there was a time when taxonomic stability was a goal, it now seems that the number of bird species is destined to be forever in flux. Some authors have suggested, for example, that DNA analyses and changes in species concepts will result in more than 20,000 species of birds being identified in the not-too-distant future. As our conservation priorities continue to focus on species that are endangered and threatened species, there may benefits in the apparent chaos of species proliferation from discoveries in the lab.

Further Reading

de Léry J (1578) Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Bresil, autrement dite Amérique. La Rochelle ou Genève: Antoine Chuppin. VIEW

Edwards G (1743) A natural history of uncommon birds. London: G. Edwards. VIEW

Gould J. (1849) A monograph of the Trochilidæ, or family of humming-birds. London : Published by the author. VIEW

Jardine W (1833) The natural history of hummingbirds. Edinburgh: WH Lizars. VIEW

Lesson RP (1829) Histoire naturelle des oiseaux-mouches. Paris: Arthus Bertrand. VIEW

Marcgrave G (1648) Historiae Naturalis Brasiliae, Liber Quintus, Qui agit de Avibus. Lugdun: Batavorum, Apud Franciscum Hackium. VIEW

Mulsant MÉ, Verreaux E (1874) Histoire naturelle des oiseaux-mouches, ou, Colibris constituant la famille des trochilidés. Lyon: Au Bureau de la Société Linnéenne. VIEW

Sornoza-Molina F, Freile JF, Nilsson J, Krabbe N, Bonaccorso E (2018) A striking, critically endangered, new species of hillstar (Trochilidae: Oreotrochilus) from the southwestern Andes of Ecuador. The Auk 135: 1146–1171. VIEW

Whatley J (1990) History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. Translation of de Léry J (1578) and introduction by Janet Whatley. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Williamson JL et al. (2024) Extreme elevational migration spurred cryptic speciation in giant hummingbirds. PNAS 121: e2313599121. VIEW

Image Credits

Book cover and chart by the author

Hummingbird engravings all from the monographs, in the public domain

Hummingbird photographs from Wikipedia Commons