LINKED PAPER

Approaching birds with drones: first experiments and ethical guidelines.

Vas E. Lescroël A. Duriez O. Boguszewski G. Grémillet D. 2015.

Biology Letters. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0754

The progress of robotics and miniaturization have enabled the use of robots in many areas of science, including ecology, where they can observe, collect samples and explore areas inaccessible to humans (Grémillet et al. 2012).

At present, some types of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have a very low price, which makes them accessible for the general public and the scientific community (Jones et al. 2006). Some studies on wildlife, either on birds (Sarda`-Palomera et al, 2011, Chabot and Bird, 2012) or other taxa (Vermeulen et al. 2013) have already been performed with fixed-wing UAVs.

For our study, we used a quadricopter drone controlled from the ground by a pilot, allowing rapid adjustment of altitude and speed. This tool can be very interesting for environmentalists and particularly for land inventories, however, facing the craze for this type of drone it is important to lay the foundations and establish regulations that will regulate this type of practice. This was the purpose of our study published on February 4, 2015, namely the study of the behavioral response of the birds to the use of motor drones, leading to ethical guidelines.

Context of the study

The project was part of my masters at the CEFE-CNRS, in collaboration with the startup Cyleone, specialized in electronics and robotics. Cyleone is developing drone-based data acquisition, and was interested in designing a flying Protocol that would allow environmentalists to use drones for inventories while minimizing the impact that the presence of the device may have on birds. I was particularly interested in this topic since my master dealt with the application of new technologies to environmental research. Further, this study was conducted in collaboration with David Grémillet, Amélie Lescroël and Olivier Duriez, all researchers in ecology at the CEFE-CNRS, so I was operating at the interface between academia and the industry.

We proceeded to finding an area where we could perform these tests legally with the consent of the competent authorities, in particular managers of natural areas concerned To strengthen our case we initially conducted tests on mallards at the zoo of Lunaret (Montpellier) with the support of its director, Luc Gomel. Since the tests were very encouraging we moved to a wetland of the Camargue, the Cros Martin (near Montpellier).

The image on the left is the aerial view taken by the drone of the land area of the Lunaret zoo; on the right is the aerial view of the Cros Martin wetland

The first flights in the natural area were made in the presence of managers who were able to see the possible applications of the use of drones for environmental expertise.

French law

To fly with a drone in France you have to request authorization from the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) and describe your flight plan precisely (the altitude where you want to fly, the area where you want to fly . . .). After the approval of the DGCA we had a flight plan showing the prohibited areas for passage with the drone and the authorized areas, but having the agreement of the DGAC was not sufficient since the Cros Martin area is a protected natural area. It was therefore necessary to have the agreement of the RDEPH (Regional Directorate of Environment, Planning and Housing), the Cros Martin managers and of the nearby municipality of Candillargues. Finally, the experiments were performed under permit of the French veterinary services, for aspects directly related to animal welfare. The drone used is approved by the DGCA, has a registration number, and is known to the authorities, as is its pilot (Mathieu Héraud), who is a professional, licensed pilot working for Cyleone, with the corresponding Skill Level Declaration (SLD) certification.

The flight protocol

The drone used is a common type of drone, relatively simple with its small size allowing easy deployment on the ground. This drone is a Phantom model with a GoPro camera whose image quality was sufficient for our purpose; it is the drone of the Cyleone Company:

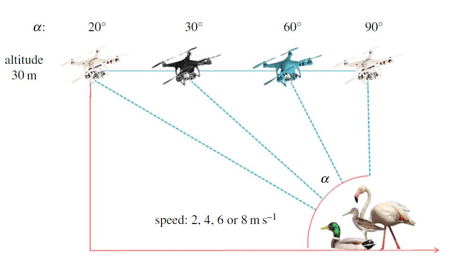

Several variables were taken into account and tested, such as the effect of the color of the drone, approach speed, position relative to the bird and approach altitude. In the field, other parameters were protocoled, such as brightness, wind speed, and distance between the birds and the drone. The pilot first ascended the drone to 30 meters. Once at that altitude the drone approached birds at different angles (20, 30, 60 and 90 degrees) and with different speeds (2, 4, 6 and 8 m/s). As the drone was approaching the birds, an observer equipped with binoculars observed any reaction from the birds. If a reaction was visible, the drone was stopped, the position of the drone relative to the birds noted, and the drone flown back to its starting position. These flights were also repeated with different colors of drone.

The results observed

We performed a total of 204 Approaches in 8 days (24-36 per day): 48 mallards in semi-captive conditions and on 156 further occasions, wild greenshanks (60 trials) and flamingos (96 trials) were approached.

The results of the different tests were surprising to us because we expected birds to show reactions to almost any approach type, even from the take-off of the drone. Actually birds seldom reacted. Reactions were only noticeable when we used the 90° approach, when the drone was just above individuals. In 80% of all cases, birds ignored the drone. We also noted the influence of group size; larger groups tended to show a stronger response to drone presence.

Our protocol should be tested by adding new factors (such as the size of the drone, different times of the nesting season), to understand whether drones can really be used more generally for wildlife research.

It must be borne in mind that the purpose of our study was to develop a code of ethics that would equally help drone users and wildlife managers. Drones are becoming far more accessible in the research community, and our aim is to anticipate this use, to minimize the negative effects that these devices may have on bird behavior. Overall, the goal is to protect the well-being of individual animals and not to distress them by using drones regardless of their impact.

Our study was the first to experimentally test the effect of drones and their use on birds, to work towards writing a manual of good conduct for drone uses in wildlife research. We hope to be able to perform similar tests on other bird species. For instance, birds of prey tend to attack drones and there is an urgent need for clearer guidelines when dealing with this particular group.

References and further reading

Chabot, D., Bird, DM. 2012. Evaluation of an off-theshelf unmanned aircraft system for surveying flocks of geese. Waterbirds 35: 170–174. DOI: 10.1675/063.035.0119

Grémillet, D., Puech, W., Garçon, V., Boulinier, T., Le Maho, Y. 2012. Robots in Ecology: Welcome to the machine. Open Journal of Ecology 2(2): 49-57. DOI: 10.4236/oje.2012.22006

Jones, GP., Pearlstine, LG., Percival, HF. 2006 An assessment of small unmanned aerial vehicles for wildlife research. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 34: 750–758. DOI: 10.2193/0091-748(2006)34[750:AAOSUA]2.0.CO;2

Sarda` -Palomera, F., Bota, G., Vin˜Olo, C., Pallare´s, O., Sazatornil, V., Brotons, L., Goma´ rize, S., Sarda, F. 2011. Fine-scale bird monitoring from light unmanned aircraft systems. Ibis 154(1): 177-183. DOI: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2011.01177.x

Vas, E., Lescroël, A., Duriez, O., Boguszewski, G., Grémillet, D. 2015. Approaching birds with drones: first experiments and ethical guidelines. Biology Letters 11(2). DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0754

Vermeulen, C., Lejeune, P., Lisein, J., Sawadogo, P., Bouché, P. 2013. Unmanned Aerial Survey of Elephants. Plos ONE 8(20).DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054700