Whilst surveying Newfoundland’s seabird colonies for the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1973, I was keen to learn the local names for the birds. Fishermen in the myriad tiny outports spent their lives on the sea, mainly fishing cod, and had names for most of the birds they saw regularly and sometimes hunted. I spent most of that summer in Witless Bay working on the fabulous colonies numbering more than a million breeding seabirds. The three local fishermen who ferried me to and from those colonies really new their birds and were often amused at the ‘proper’ names that I used. It was eventually easier, and more fun, for me to use the folk names.

It was not long before I was on a ‘first-name’ basis with the tickle-ass (kittiwake), turr (murre/guillemot), bawk (shearwater), noddy (fulmar), sea parrot (puffin), Mother Carey’s Chicken (Leach’s Storm Petrel), tinker (Razorbill), and sea pigeon (Black Guillemot). At outports farther north, I learned that Great Black-backed Gulls were ‘saddlebacks’, Long-tailed Ducks were ‘hounds’, and Buffleheads were ‘butterballs’. Many of these folk names will be familiar to European readers as they were brought over from the Old World by the earliest settlers (Swann 1913). My favourite, though, and probably unique to Newfoundland as long as 300 years ago (see below), was their name for the Harlequin Duck—Lords and Ladies.

The name ‘Lords and Ladies’ refers to drakes and hens but it seems to be used collectively even for a single bird, possibly because this species is usually seen in groups. This reminds me of an expression I found amusing in France. There, shop-keepers and restaurant maîtres d often greeted me as ‘messieurs-mesdames’ even if I was alone or with one or more of my male colleagues.

Porcelain of Arlecchio ~1738

The Harlequin Duck was one of the first birds first given a ‘scientific’ binomial by Linnaeus in the tenth (1758) edition of his monumental Systema Naturae. In that edition, he introduced what we now call Linnaean taxonomy, whereby each species is given Latinized genus and species names. Linnaeus called this duck Anas histrionica, in the order Anseres. Anas is the Latin word for duck, and histrionica is from the Latin word ‘histrio’, or actor. Presumably, Linnaeus thought their plumage resembled the costume of the Arlecchino, the role played by an actor in the Commedia dell’arte, a popular form of theatre in Europe from the 1500s to the 1700s. Linnaeus (wisely) did not provide vernacular names so it was not until 1785 that this species was called the Harlequin (Pennant 1785) presumably with reference to that same character, Arlecchio.

Linnaeus’s (1758) description of Anas histrionica

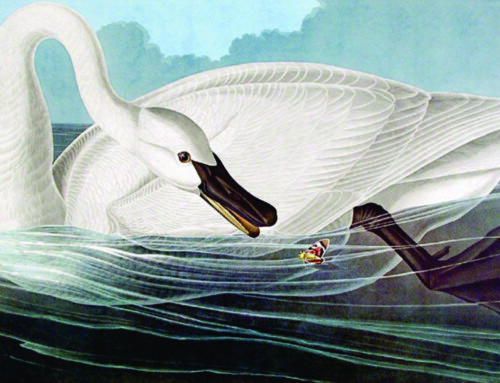

Linnaeus attributed to George Edwards [1694-1773] the first published description and illustration of this species, in Edwards’s (1745) A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Edwards wrote on the published engraving that he produced it in September 1745. He called this species ‘The Dusky and Spotted Duck’, a name that thankfully never caught on. He says: “This Bird was brought with others, preserved, from Newfoundland in America: It was lent me by Mr. Holms, of the Tower of London; he says the Newfoundland Fishers call it the Lord, for what Reason I cannot tell; but I suppose the Reason of this Name may be from the Likeness of a Chain it has about its Neck, seeing the wearing of Gold Chains is an antient [sic] Mark of Dignity in Europe.” His description is detailed and his engraving is unmistakably a male Harlequin Duck.

Harlequin Duck from Edwards (1745)

For every species of bird, there is supposed to be a type ‘specimen’, usually the original specimen associated with the first published description of the species starting with Linnaeus (1758). But there is no ‘type specimen’ for the Harlequin Duck in a museum, only Edwards’s engraving and description. This is called a ‘designated type: “Designation of an illustration of a single specimen as a holotype is to be treated as designation of the specimen illustrated; the fact that the specimen no longer exists or cannot be traced does not of itself invalidate the designation.” (ICZN 1999). Many of the first specimens of birds, like that of the Harlequin Duck, were long ago lost to fires, insects, or negligence.

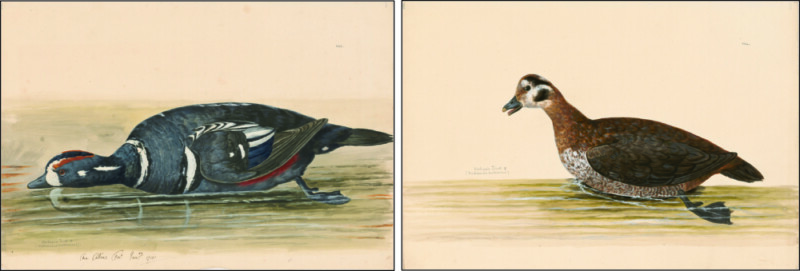

In Edwards description of the Harlequin Duck, he says “I cannot discover any Figure, or the least Hint of Description of this Bird; so I believe I may venture to pronounce it a non descript.” But he was wrong, for, in January 1741, Charles Collins [1670-1744] painted a male Harlequin Duck for his patron Taylor White. Later, between 1744 and 1722, Peter Paillou [1720-1790] painted the female for White. Both birds are accurately and exquisitely painted. Both sexes are depicted on the water, though the male is lying (or maybe displaying?) on the surface. Collins’s male looks to me like the same bird that Edwards illustrated almost five years later.

Taylor White [1701-1772] was a jurist who travelled widely around England performing his duties. He was also a keen naturalist and art collector who was largely responsible for building up the London Foundling Hospital’s famous collection of art. He was also a patron of artists, commissioning about 1500 paintings by some of the best natural history artists of the day. This was Taylor White’s ‘paper museum’ that he never published (Dickenson & Garland 2021). Instead, he showed his collection to many interested people where he lived and travelled. Now, 938 paintings from that collection are housed at the fabulous Blacker Wood Natural History Collection at McGill University in Montreal and can be viewed online here. This collection includes 443 paintings of birds accurately painted at life size (Javidi and Montgomerie 2021).

Paintings in the Taylor White Collection: male by Charles Collins, female by Peter Paillou

Collins’s painting of the male Harlequin Duck says on the back, in Taylor White’s hand: “This from Newfoundland the label was made in Lond. This bird is undescribed unless ’tis the Scaup W. 365 & that description is too imperfect to form a judgement from.” ‘W. 365’ refers to page 365 in Ray’s (and Willughby’s) monumental Ornithology of 1678, but their description really is a (Greater or Lesser) Scaup. White often obtained preserved, and sometimes live, specimens from explorers and traders arriving in London from the Americas, Africa, and India. Once he had commissioned those paintings he probably donated many of the specimens to the museum and menagerie at the Tower of London. Rather curiously, he did not seem to notice that Edwards (1745) had described this species—White regularly reorganized and annotated his paintings until he died in 1772 (Dickenson & Garland 2021).

And Edwards clearly knew White, as he mentions him in at least six species accounts in his ‘Uncommon Birds’ (MacGregor 2014). Edwards and White would have socialized in the same circles of naturalists and White made it a point to exhibit his paper museum at his lodgings. All of us forget when and where we saw birds and heard interesting ideas, so I cannot fault Edwards not acknowledging White having Collins’s painting of the Harlequin Duck. It’s too bad, though, that Collins’s painting is not the designated type as it is more life-like, more accurate, and probably made from the same specimen as Edwards used for his engraving.

Further Reading

Dickenson, V., Garland, J. (2021) Taylor White’s ‘paper museum’. Notes and Records of the Royal Society 75:599–626. VIEW

Edwards, G. (1745) A Natural History of Uncommon Birds, Part II. G. Edwards, London. VIEW

ICZN [International Code of Zoological Nomenclature] (1999) VIEW

Javidi, V., Montgomerie, R. (2021) Ornithological insights from Taylor White’s birds. Notes and Records of the Royal Society 75:581–598. VIEW

Linné, C. von [Linnaeus] (1758) Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. [The system of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera, species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places.]. Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae [Stockholm]. 824 p. VIEW

MacGregor, A. (2014) Patrons and collectors: contributors of zoological subjects to the works of George Edwards (1694–1773). Journal of the History of Collections 26: 35–44. VIEW

Pennant, T. (1785) Arctic Zoology, Vol. 2. Henry Hughs, London. VIEW

Ray, J. (1678) The Ornithology of Francis Willughby. John Martyn, London. VIEW

Scribner, K.T., Talbot, S.L., Pierson, B.J., Robinson, J.D., Lanctot, R.B., Esler, D., Dickson, K. (2024) A phylogeographical study of the discontinuously distributed Harlequin Duck (Histrionicus histrionicus). Ibis 166: 1218-1240.VIEW

Swann, H.K. (1913) A Dictionary of English and Folk-names of British Birds. With their history, meaning and first usage; and the folk-lore, weather-lore, legends, etc., relating to the more familiar species. Witherby & Co., London. VIEW

Image credits

All in the public domain

Images from Linnaeus (1758) and Edwards (1745) at the links above

Arlecchio from Meissen Manufactory, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons (here)

Paintings by Collins and Paillou from the Taylor White collection at McGill University (here)