LINKED PAPER

Vocal traits of shorebird chicks are related to body mass and sex. Kostoglou, K. N., Miller, E. H., Weston, M. A., & Wilson, D. R. 2022. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13055. VIEW

As individuals mature, their voice undergoes changes. You might remember what happened during puberty when the pitch of your voice dropped with the occasional voice cracks as a result. A similar process might take place in young birds. As chicks develop, their vocalisations might change in pitch or rhythm (Adret 2012, Dragonetti et al. 2013). In a recent study, a team of international ornithologists studied this process in two shorebird species: the Red-capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus) and the Southern Masked Lapwing (Vanellus miles novaehollandiae). The study aimed to explore how the vocal traits of these bird species’ chicks change as they grow older.

Recordings

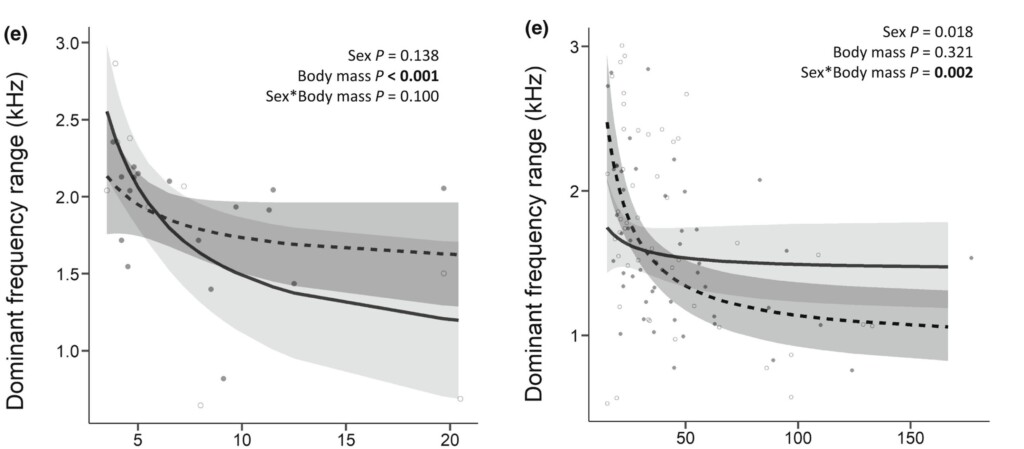

While studying the two species in the Cheetham Wetlands (Australia), the researchers brought the chicks to a sheltered location to record their squeaks and chirps. In total, they collected 2600 vocalisations of 26 Red-capped Plovers and 6835 vocalisations of 95 Southern Masked Lapwings. Using body mass as a proxy for age, the researchers discovered that the frequency range of the plovers decreased as the chicks grew older. Similarly, the vocalizations of older lapwings occurred at lower frequencies. Notably, this effect was more pronounced in male lapwings. These findings provide clear evidence that the vocalizations of shorebirds undergo changes during their development.

Figure 1.In both Red-capped Plovers (left) and Southern Masked Lapwings (right), the dominant frequency range of chicks decreased with weight (a proxy for age). In lapwings, the effect was stronger in males (hatched lines) compared to females (solid line).

Communication

The exact mechanism underlying these vocal changes remains to be determined. Possibly, the larger bill size of older chicks limits their ability of modulating between frequencies (Demery et al. 2021). Or the vocal tracts have changed during development (Zonov 2011). Regardless of the underlying mechanism, the relationship between vocalisations and age might play a role in parent-offspring communication. Developmental changes in the squeaks of chicks might allow parents to assess the condition of their offspring, and adjust their parental care accordingly (Goedert et al. 2014). There might be more to a chick squeak than we think.

References

Adret, P. (2012). Call development in captive-reared Pied Avocets, Recurvirostra avosetta. Journal of Ornithology 153: 535– 546. VIEW

Demery, A.-J.-C., Burns, K.J. & Mason, N.A. (2021). Bill size, bill shape, and body size constrain bird song evolution on a macroevolutionary scale. Ornithology 138: 1– 11. VIEW

Dragonetti, M., Caccamo, C., Corsi, F., Farsi, F., Giovacchini, P., Pollonara, E. & Giunchi, D. (2013). The vocal repertoire of the Eurasian Stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125: 34– 49. VIEW

Goedert, D., Dias, R.I. & Macedo, R.H. (2014). Nestling use of alternative acoustic antipredator responses is related to immune condition and social context. Animal Behaviour 91: 161– 169. VIEW

Zvonov, B.M. (2011). Ways of developing acoustic signals in birds. Biology Bulletin Reviews 1: 552– 559. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Red-capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus) | Benjamint444 | CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here