LINKED PAPER

Geolocator tagging reveals Pacific migration of Red-necked Phalarope Phalaropus lobatus breeding in Scotland. Smith, M., Bolton, M., Okill, D.J., Summers, R.W., Ellis, P., Liechti, F. & Wilson, J.D.

IBIS 156: 870-873. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12196

In our short communication (Smith et al. 2014) in the latest issue of IBIS we describe discovering a quite remarkable migration route using 0.6g geolocators.

Red-necked Phalaropes are a high priority species for the RSPB in Shetland, where we manage some of their key breeding sites and monitor the population annually. We introduced a colour-ringing scheme in the mid 1990s and have marked a large number of birds since – I’ve personally ringed over 500 birds since 1998. This has provided us with loads of demographic data, which we hope will soon be published after being analysed by Amanda Biggins.

What our ringing programme failed to tell us was where our birds wintered. We have had only a single sighting of one of our birds outside of Shetland – a colour-ringed juvenile spotted by an eagle-eyed birder in Hampshire in October 2005! This was quite exciting at the time, but really only told us that our birds move south in autumn.

I’ve been keeping an eye on the development of geolocators for several years and was delighted when I discovered in the winter of 2011/12 that they were finally small enough to attach to phalaropes. At last, an opportunity to find out where my favourite birds spend most of the year!

We had ten 0.6g tags made up for us by our colleagues at the Swiss Ornithological Institute. We had a lot of help from Ron Summers, who came up to Fetlar in Shetland to help us construct a harnesses and we fitted the tags onto six males and four females in June 2012. We mostly used mist-nets to capture birds, but also used walk-in nest traps to capture some of the males. My Shetland Ringing Group pals Dave Okill and George Petrie were instrumental in helping to catch these birds. The tags had little apparent effect on the birds after we fitted them – some of them were seen copulating within minutes of being released!

I’d noticed that one male appeared to have lost its tag, which was a bit of a worry and should have acted as a warning for problems ahead. Incredibly, my colleague Martha Devine was walking round a pool monitoring Red-throated Diver nests out on the hill some time later and found the discarded tag by the water’s edge. This was a site rarely used by phalaropes and was over 3km from his capture site. It was redeployed onto another bird. I began to worry a bit when I discovered a second bird had also lost its tag before it left in the autumn.

It was an anxious winter, waiting to see if any of our birds would return and if any would still have their tags attached! There was real excitement on 28 May 2013 when I found one of our tagged birds back at one of our managed sites on Fetlar with her tag still attached. We knew from the start that females would be a lot more difficult to recapture than males as they tend to flit around between sites looking for potential mates and have no association with their nests or chicks. We weren’t quite prepared for the amount of effort needed to catch this one bird – we failed to catch her after fifteen days of trying! This was a huge frustration, not helped by the fact that two of the tagged birds had returned minus their tags. The project was beginning to feel like a failure and morale was beginning to flag, especially for Dave and George who had a 5-6 hour return journey for each visit.

Things started looking up when I found a tagged male on 19 June – he was a sneaky devil! He’d reached incubating stage without me even knowing he was back. This was a game-changer! With Martha’s help we managed to find his nest and contacted Dave and George so they could come up the next day to try and trap him on his nest.

We knew through experience that using a walk-in trap was almost always successful with incubating male phalaropes, so I was confident of success and, sure enough, we got our hands on his tag the following morning. We had a well-deserved dram of Scotland’s finest that night!

There was a bit of a problem with having the data interpreted, with colleagues from the RSPB and the Swiss Ornithological Institute becoming involved in making sense of what was pretty messy data. I remember reading emails which included phrases like ‘impossible to interpret- which was not encouraging. I was eventually given the ‘cleaned up- details by email which nearly knocked me off my seat.

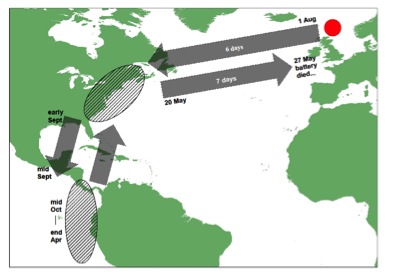

We knew that the south-eastern Pacific was an important wintering area for North American phalaropes, but didn’t expect our birds to be joining them.

So, where do we go from here? Well, obviously we want to get data from more birds! We have deployed similar geolocators onto a further 10 phalaropes this summer – five males and five females. We have, I hope, sorted out the problem with the harness from the previous project – it was my fault for using cheap epoxy resin. This time we used some stuff that cost over £20 that we got from a chandler’s in Lerwick.

I believe that geolocators were attached to Red-necked Phalaropes elsewhere in their breeding range last year and this summer – so we should be hearing about results from last years birds soon. It’ll be interesting to start getting a clearer picture of how our birds fit into the bigger picture – do all our birds winter in the Pacific? If so, does this mean that the Shetland birds are actually part of the North American population rather than the North European population?

Also in the future, it would be tempting to investigate the movements of juvenile birds which may help to understand what our ringed bird in 2005 was up to?