The word ‘syrinx’ probably entered the entered the English lexicon in 1606 in The Rev Nathaniel Baxter’s long poem entitled ‘Sir Philip Sydney’s Ourania’. In the poem, Baxter muses about the planets, the Earth and its inhabitants, the elements, and the meaning of life. Of the birds he says:

The Eagle, Griffin, Falcon, Marlion [Merlin],

The Nightingale, and turtle Pigeon [turtle dove],

The Thrush, the Lynnet, and mounting Lark,

Besides the Birds that fly in the dark,

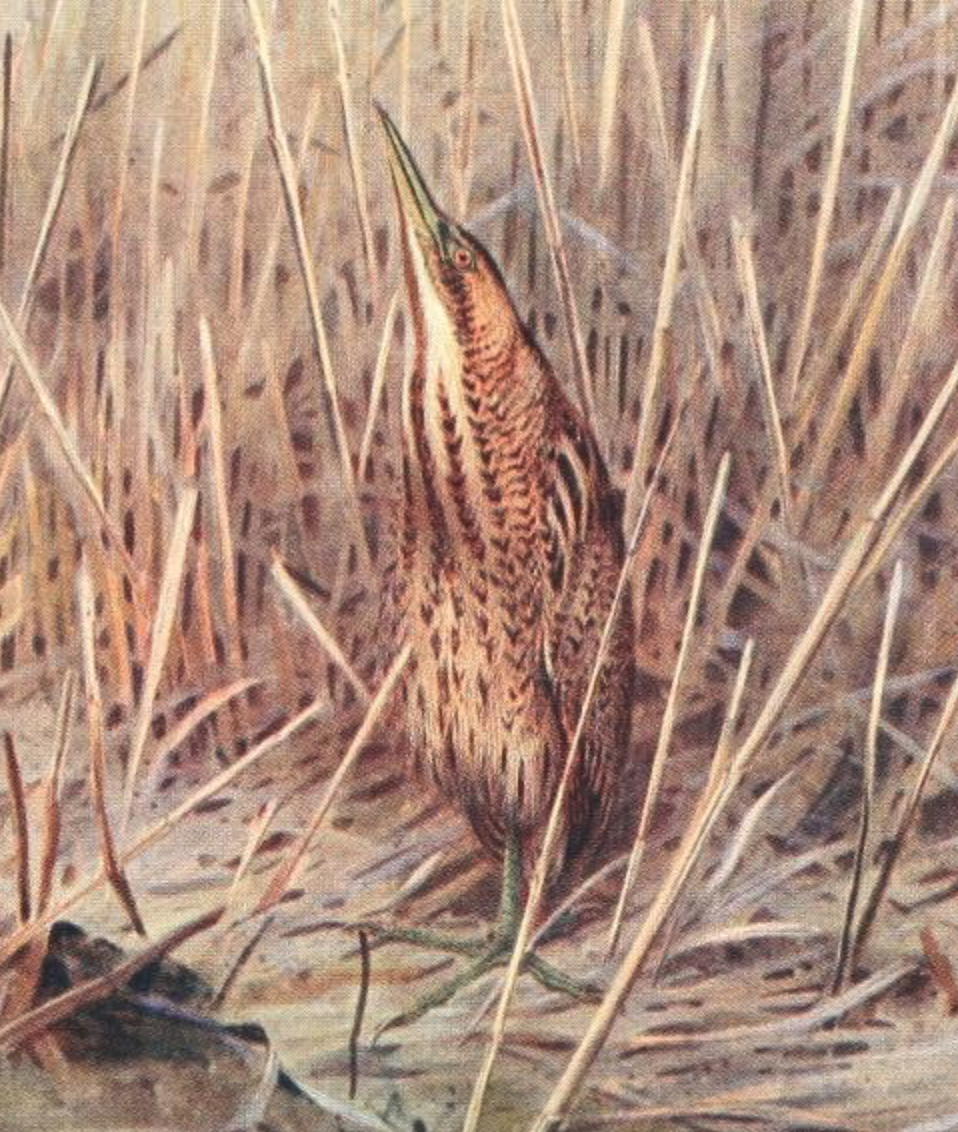

The Bittern piping in a Syrinx Reed,

Wailing that virgin’s loss in mourning weed.

With Birds of Price and worth Innumerable,

Wherewith great states garnish their Table.

Here, he is saying that the bittern sounds like ‘syrinx reeds’, an early name for panpipes. Syrinx (Σῦριγξ) in classical Greek mythology was a beautiful wood nymph, known for her chastity. When the randy god Pan, often pictured as a satyr, pursued her, Syrinx asked the river nymphs to transform her into a few hollow water reeds. Pan found those reeds, cut them, and constructed what we now call panpipes. Panpipes produce a hollow sound (here) when one blows across the open ends of the pipes, reminding Baxter, I assume, of the mating call of the Eurasian Bittern (here).

The term ‘syrinx’, however, was not applied to the voice box of birds until 1871 when Thomas H. Huxley described it in his A Manual of the Anatomy of the Vertebrated Animals: “Birds possess a larynx in the ordinary position; but it is another apparatus, the lower larynx or syrinx, developed either at the end of the trachea, or at the commencement of each bronchus, which is their great vocal organ.” As Huxley notes, the avian syrinx was previously called the ‘lower larynx’— by the time he wrote it had been well studied anatomically. We do not know why he sed the term ’syrinx’ here but my guess is that he knew about panpipes and liked the sound of the term in comparison to the well-known ‘larynx’ of mammals and other vertebrates.

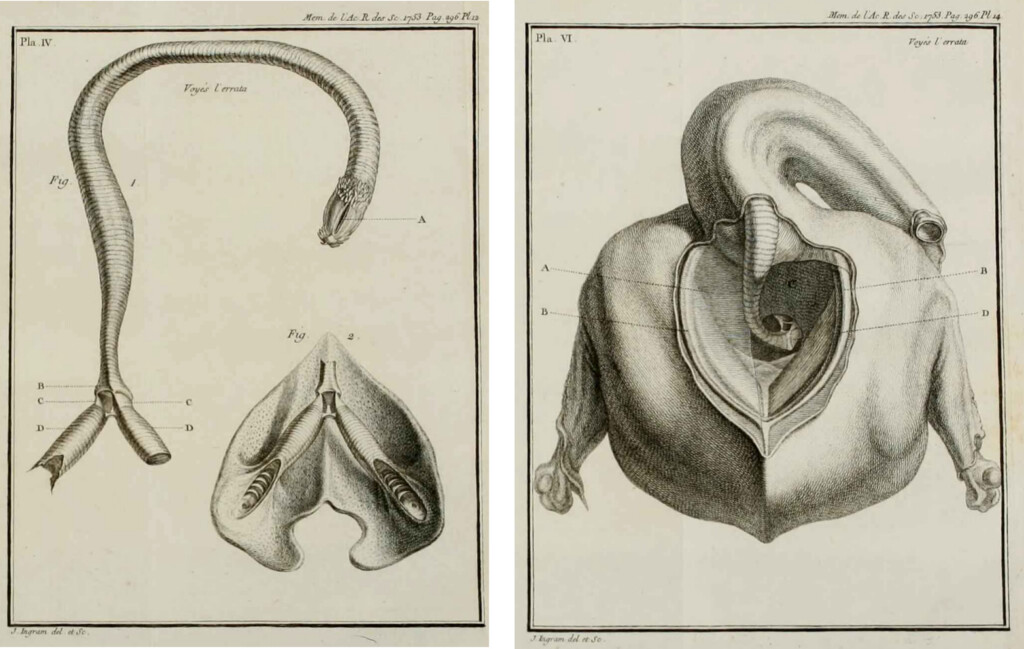

Huxley’s terminology was adopted right away—by 1896 Alfred Newton devoted six pages in his Dictionary of Birds to the topic of SYRINX. There, Newton noted that three types of syrinx are distinguishable (Tracheal, Bronchial, and Tracheal-Bronchial but that it was still a mystery how the syrinx produced songs; “The essential requirement of a vocal organ, the presence of vibratory membranes, can be met in many ways; but how these membranes act in particular, and how their tension is modified by the often numerous muscles we do not know. Various dilatations of the Trachea no doubt assist the modulation of the voice, and the same may be said of the upper Larynx; but the Tongue plays no part in the voice of Birds, with the possible exception of Parrots, and the slitting of that member or the c utting of its frenum cannot possibly add to the faculty of articulation.”

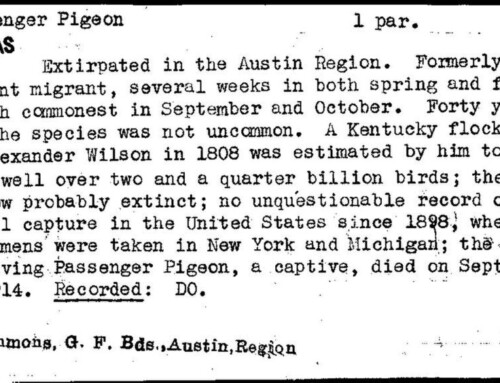

In 1753, the French physician and anatomist François David Hérissant [1714–1773] was the first to describe and illustrate the ‘lower larynx’ of birds and recognize it as the source of their calls and songs: “The main organs responsible for the formation of birds’ voices consist of various membranes that are more or less flexible, more or less taut, and positioned in various directions. In certain birds, such as the goose, etc., there are four of these membranes (C, same figure), shaped and arranged in much the same way as the two parts of an oboe reed. These four membranes, arranged in pairs, form, as it were, two kinds of membranous reeds, the upper part of which originates from two oblong mouthpieces of the internal larynx; these reeds then end at their lower part at the origin of the first two bronchi of the trachea (D, same figure).” [translated from the original French]

For the next 150 years, studies of the syrinx focussed on describing the details of its structure in different species and using the ‘lower larynx’ to make inferences about taxonomic relationships. In his 1843 A History of British Birds, for example, William Yarrell correctly noted that different families and genera of birds had distinctly different syringes. Then, following a succession of studies by various authors outlining the key differences between various groups in the structure of the syrinx, William Pycraft in 1910 correctly interpreted syringeal morphology as having useful implications for both taxonomy and avian evolution.

The syrinx is unique to birds, having arisen as a novel structure likely associated with the evolution of continuous breathing, in the early history of modern birds. Thus the syrinx is unusual in that it replaced an already functional structure (the larynx) in a new location, possibly taking advantage of a change in respiration associated with flight.

In the early twentieth century, attention turned to answering Newton’s questions about function. While considerable progress has been made in understanding how the syrinx works, it’s still a bit of a mystery how a tiny bird like the wren, with a minuscule syrinx, can produce a song so loud that it can be heard hundreds of metres away (Ziegenhorn et al. 2026).

Further Reading

Hérissant, F.D. 1753. Recherches sur les organes de la voix des quadrupedes et de celle des oiseaux. Mémoires de l’Academie Royale des Sciences de l’Institut de France, Paris, pp 279–295. VIEW

Huxley, T.H. 1871. A Manual of the Anatomy of the Vertebrated Animals. J. &. A. Churchill, London. VIEW

Kingsley, E.P., Eliason, C.M., Riede, T., Li, Z., Hiscock, T.W., Farnsworth, M., Thomson, S.L., Goller, F., Tabin, C.J. & Clarke, J.A. 2018. Identity and novelty in the avian syrinx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115: 10209–10217. VIEW

Newton, A. 1896. A Dictionary of Birds. A & C Black, London.VIEW

Yarrell, W. 1843. A History of British Birds, Vols 1-3. John Van Voorst, London. VIEW

Pycraft, W.P. 1910. A History of Birds. Methuen Co., London. VIEW

Ziegenhorn, M.A., Lanctot, R.B., Brown, S.C., Saalfeld, S.T., Smith, P.A. & Lecomte, N. 2026. Source amplitude increases with body-mass across avian genera. Ibis 168: 127–139.VIEW

Image Credits

European Bittern: from Pycraft (1910), in the public domain

Panpipes: from Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

Diversity of syringes: from Pycraft (1910), in the public domain

Phylogeny: from Kingsley et al. 2018