In the late 1600s, the great British naturalist, John Ray—and his friend/teacher Francis Willughby—revolutionized the study of plants and animals by adopting the emerging scientific approach that requires evidence, an in-depth study of anatomy/structure, and an attempt to classify into groups of organisms with similar structure. Thus for their published works on birds, fishes, plants, and insects they wanted to see and study each species, rejecting hearsay, fables, and fanciful creatures that often populated the books of their predecessors. Their work on birds—Ornitologiae Tres Libris (1676, in Latin) and The Ornithology of Francis Willughby (1678, in English)—is often considered to herald the beginnings of scientific ornithology (Birkhead 2008, 2016) and laid the ground work for the classification system developed by Linnaeus half a century later, and then to Darwin’s magnum opus in 1859.

Ray was literally a Renaissance man, publishing major works on words, proverbs, games, and philosophy/theology as well as his plant and animal volumes. He lists thousands of aphorisms in his A compleat collection of English proverbs (1670) and provides analysis of their origins, meanings, and usefulness. On page 283 of the first edition, in his list of Scottish Proverbs, he includes ‘Better a fowl in hand nor two flying’. That may be the first time that a version of ‘A bird in the and is worth two in the bush’ appeared in English, even though variations on the concept date back to the early years of Christianity. The phrase apparently derives from falconry, but what does it mean?

Some say that it suggests that there is value in certainty or possession (one in the hand) over the reaping of uncertain, but greater rewards (two in the bush). Another possibility is to say that having a tame falcon on the hand will result in more game from the bush, captured by the falcon. As an ecologist, I always likened the phrase to the use of mark-recapture studies to estimate population size, where the number of birds caught, marked, and subsequently recaptured could be used to calculate the density of that species in the study area.

In his review of Bird Observatories in the Ibis in 1959, R.K. Cornwallis held that they showed considerable promise for “visual observations, ringing, and critical examination of birds in the hand”. Whilst spring and fall ringing made substantial contributions to our understanding of the timing, survival, and routes taken by migratory birds, progress was slow because recovery rates of ringed songbirds are usually less than 1% and most ringed birds are recovered relatively close to where they were first caught. Now the magic of eBird, Motus, and Icarus has provided much better information on migratory routes worldwide. In a few short years, the billions of checklists provided to eBird by citizen scientists far surpassed the information on the routes and timing of migration collected from the previous hundred years of ringing more than 70 million birds in North America alone.

In the early 1960s, I volunteered at the nascent Long Point Bird Observatory (LPBO) on the north shore of Lake Erie, Ontario. LPBO was the first bird observatory in North America, established in 1960 by a coterie of British expats who were familiar with the excellent bird observatories in the UK (Cornwallis 1959). The first bird observatory worldwide was established by Heinrich Gätke (1814-1897) in the late 1800s on the archipelago of Heligoland in the North Sea, 45 km off the coast of Germany. His 1891 Heligoland as an Ornithological Observatory amply documented the value of such an observatory and inspired the creation of other bird observatories of which there are now more than 100 worldwide. The first bird observatory in the UK was established on Skokholm in 1933 by Richard Lockley and there are now at least 20 spanning the length of the British Isles from Fair Isle Bird Observatory in Shetland to Alderney Bird Observatory in the Channel Islands. The majority of observatories today are on peninsulas and islands where migrants tend to congregate and thousands of songbirds can be ringed in a single season.

Early on at LPBO, we appreciated that learning about the bird in the hand might be much more useful than having the faint hope that a few of the thousands of birds we ringed would be recovered somewhere interesting. With a bird in the hand, useful measurements can be taken, plumage colours measured, ectoparasites sampled, physiology and moults assessed, and the age of each individual determined (e.g., Dufour et al. 2025), As early as 1965, for example, we were able to determine whether young-of-the-year Least Flycatchers accompany the adults in their southward journey. They don’t, at least when passing through southern Ontario (Hussell et al. 1967).

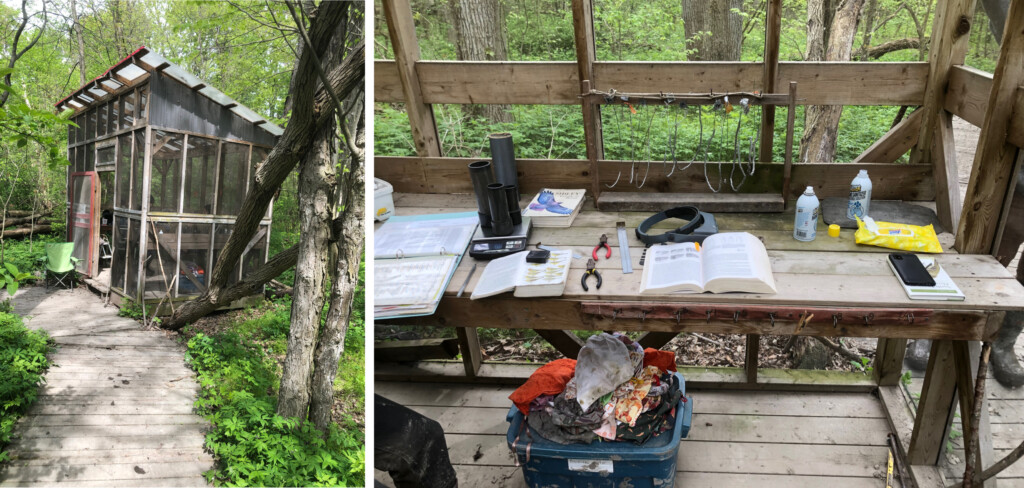

I spent the past week on Pelee Island, the southernmost inhabited land mass in Canada, and a world-class migration hotspot. There, in 2004, the Pelee Island Bird Observatory (PIBO) was established in the midst of a superb stand of Carolinian forest. Like many other observatories, they continue to fulfill Cornwallis’s (1959) promise for the future of observatories—ringing, censusing, and studying birds in the hand. But I was also impressed with their outreach programs, allowing visitors to see the catching/banding/measuring process and to learn first-hand about the birds and the ongoing research. Many who visited PIBO last week told me that it was their first introduction to birds and birding, inspiring them to get out in nature more often and to pay more attention to environmental issues. Such observatories are often run by volunteers and funded by donations form the public. They deserve our support as there may be few better ways to make a connection with the natural world than seeing, closeup, a bird in the hand.

Further Reading

Birkhead, T.R. 2008. The wisdom of birds: an illustrated history of ornithology. Bloomsbury, London: Bloomsbury. VIEW

Birkhead, T.R. (editor) 2016. Virtuoso by Nature: The Scientific Worlds of Francis Willughby FRS (1635-1672). Leiden: Brill. VIEW

Dufour, P., Hellström, M., Franceschi, C.D., Illa, M., Norevik, G., Cuchot, P., Tillo, S., Bolton, M., Parnaby, D., Penn, A., Spek, V.V.D., Knijff, P.D., VRS Castricum, Damian‐Picollet, S., Raitiere, W., Lavergne, S., Crochet, P. & Doniol‐Valcroze, P. 2025. Using age‐ratios to investigate the status of two Siberian Phylloscopus species in Europe. Ibis ibi.13382. VIEW

Gätke, H. 1895. Heligoland as an ornithological observatory; the result of fifty years’ experience. [translated to English by R.D. Rosenstock] Edinburgh: Douglas. VIEW

Hussell, D.J.T., Davis, T. & Montgomerie, R.D. 1967. Differential fall migration of adult and immature least flycatchers. Bird-Banding 38: 61–66. VIEW

Ray, J. 1670. A compleat collection of English proverbs; also the most celebrated proverbs of the Scotch, Italian, French, Spanish, and other languages. The whole methodically digested and illustrated with annotations, and proper explanations / By the late Rev. and learned J. Ray … To which is added, (written by the same author) a collection of English words not generally used, with their significations and original in two alphabetical catalogues; the one, of such as are proper to the northern, the other, to the southern counties. With an account of the preparing and refining such metals and minerals as are gotten in England. London: W. Otridge, S. Bladon [etc.]. VIEW

Image credits

Bird from Gätke 1895, in the public domain.

Heligoland from Wikipedia, LC-DIG-ppmsca-00573 from Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; in the public domain

Pelee Island map, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

PIBO photos by the author.