LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Structure and divergence of vocal traits in the Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus). Zazueta-Algara, J.J., Sosa-Lopez, J.R., Arizmendi M.C. & Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G. 2022 The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. doi: 10.1676/21-00066 VIEW

Woodpeckers (Family Picidae) are very conspicuous birds that inhabit almost every continent. This group exhibit diverse vocal repertories that are emitted under distinct behavioral contexts (e.g., MacRoberts & MacRoberts 1976, Winkler & Short 1978), and the Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) is no exception. This species mainly inhabits oak and pine-oak montane forests of North and Central America, from western USA south to Colombia. They also exhibit a variety of particular biological attributes, such as group living, construction of granaries as food storage, cooperative breeding, and low dispersal rate, suggesting that non-visual communication plays a key role in their life history. They usually emit vocalizations in a suite of different situations, such as when two or more birds gather in a tree with other members of the same group, when animals from the same or other species approach close to their territories, when a predator (such as a hawk) flies over their territory, when feeding nestlings, when chasing an intruder, or while defending their granaries (MacRoberts & MacRoberts 1976).

Vocalizations are not only important in woodpeckers but in all birds. As in many species, contexts include mate attraction and inter- and intraspecies recognition. Due to the variety of factors of great importance, vocalizations could be under direct or indirect selection, driven by factors such as morphological or acoustic adaptation, creation of vocal novelties via learning or assortative mating, and the promotion of evolutionary divergence.

The Acorn Woodpecker

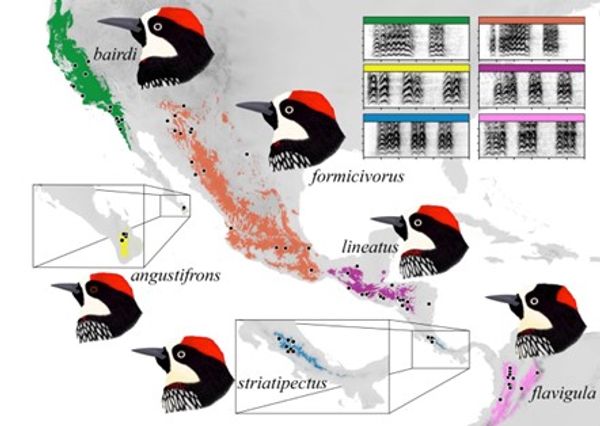

Acorn Woodpeckers have a high association to oak trees and their acorns. This species has been classified into seven subspecies based mainly on colouration and morphological size (Benítez-Díaz 1993). Most subspecies have allopatric distributions based on genetic data and have been grouped into at least four separate groups (Honey-Escandón et al. 2008). Our main goal was to explore whether vocal variation across their distribution range could reflect the evolutionary divergence in relation to morphological variation, geographic distribution, and social attributes. We also aimed to know the level of vocal divergence and if each subspecies could be distinguished based on their vocal characteristics.

Figure 1 Acorn Woodpeckers store acorns in trees named as granaries © José de Jesús Zazueta-Algara.

What did we do and what did we find?

We gathered and analyzed recordings made directly by us in the field and those avaliable in public repositories (e.g., Xeno-Canto) which represented most of the distribution and geographic variation of the species. Using the most common vocalization types, both performed in presence of intruders, two vocal groups were clearly identified: the northern vocal group (NVG) and the southern vocal group (SVG), which are separated principally by their temporal features. Divergence between both groups is huge, in such a way subspecies could be easily confused with other subspecies within their own vocal group but can be assigned accurately to their own vocal group. These vocal groups mirror the same northern-southern pattern of genetic differences, in both cases with two subspecies for the NVG (bairdi and formicivorus) and four for the SVG (angustifrons, lineatus, striatipectus and flavigula). The interesting fact is that subspecies angustifrons, either genetically or vocally is grouped in the SVG, geographically is closer to subspecies of the NVG. This two-group pattern probably dates back to the Pleistocene (Honey-Escandón et. al. 2008), and we can notice that between subspecies that delimit the groups there are two zones of major divergence: the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the Gulf of California.

Figure 2 Distribution ranges, spectrograms of calls and overall plumage patterns of Acorn Woodpecker subspecies. Black dots represent our samples. Illustrations obtained from the original artwork produced for the paper © José de Jesús Zazueta-Algara.

Bill morphology as an influencing factor

Morphological characteristics could influence some features of vocalizations, for instance the temporal ones which could be affected by bill size (Podos 2001), or vocal frequencies, which could be affected by body size. As previously mentioned, vocal groups are mainly separated by temporal features which led us to think that some bill characteristics are involved. Benitez-Díaz (1993) showed that the subspecies of the NVG have larger bill sizes, on average, compared to subspecies of the SVG. Aizen (1990) suggested the existence of a general geographic trend of acorn sizes, from larger acorns in northern oak species to smaller acorns in southern oak species. Acorns are one of the most important components of Acorn woodpecker diet, and we emphasize this because diet types exert selective pressures on bill sizes of many species. This is due to the manipulation of food, which influences jaw muscles for stronger bites (Grant & Grant 2002), and in turn, jaw muscles influence the speed of bill movements (Podos 2001), see original video below, recorded at Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico.

Our results suggested that divergence between subspecies of vocal groups could be a consequence of an indirect ecological selection on traits such as bill size, driven by their feeding adaptations to acorns.

References

Aizen, M.A. 1990. Acorn Size and Geographical Range in the North American oaks (Quercus L.). Journal of Biogeography 17: 327-332. VIEW

Benítez-Díaz, H. 1993. Geographic variation in coloration and morphology of the Acorn Woodpecker. Condor 95: 63-71. VIEW

Honey-Escandon, M., Hernández-Baños, B.E., Navarro-Sigüenza, A.G., Benítez-Díaz H. & Peterson, A.T. 2008. Phylogeographic patterns of differentiation in the Acorn Woodpecker. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120: 473-493. VIEW

Grant, P.R. & Grant B.R. 2002. Adaptive radiation of Darwin’s finches. American Scientist 90: 130-139. VIEW

MacRoberts, M.H. & MacRoberts, B.R. 1976. Social organization and behavior of the Acorn Woodpecker in central coastal California. Ornithological Monographs 21 Washington DC: American Ornithologists’ Union.

Podos, J. 2001. Correlated evolution of morphology and vocal signal structure in Darwin’s finches. Nature 409: 185-188. VIEW

Winkler, H. & Short L.L. 1978. A comparative analysis of acoustical signals in pied woodpeckers (Aves, Picoides). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 160: 1-110. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Acorn Woodpecker Melanerpes formicivorus striatipectus © Chuck Heikkinen.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.