Is over-winter survival driving population declines in a long-distance migrant?

LINKED PAPER

High within-winter and annual survival rates in a declining Afro-Palaearctic migratory bird suggest that wintering conditions do not limit populations. Blackburn, E. and Cresswell, W. 2015. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12319 VIEW

Migrant birds across the world are in decline, and interestingly the scale of these declines is often greater than those seen for non-migratory species (Sanderson et al. 2006; Vickery et al. 2014). Whilst we know that factors acting on the breeding grounds can be a major cause (such as loss of breeding habitat and reduced nesting success for farmland birds), the fact that being migratory appears to increase the chances of having a negative population trend raises the suspicion that there is something else going on outside of the breeding season (Bohning-Gaese & Bauer 1996, Sanderson et al. 2006, Heldbjerg & Fox 2008), either during migration and at stopovers, or on the wintering grounds themselves.

Knowing where mortality is occurring is vital for the conservation of these declining species; yet despite the fact that long-distant migrants spend the majority of their annual cycle either migrating or overwintering, we know very little of what goes on during this time. Studying wintering ecology is therefore a fundamental step in understanding why migrants are disappearing from the European countryside, and that means heading to the wintering grounds in sub-Saharan Africa.

Our research group has been studying wintering Palearctic migrants in Nigeria since the early 2000’s, exploring both large-scale patterns such as habitat associations, and also finer-scale aspects of wintering ecology such as site fidelity. One such species is the Whinchat Saxicola rubetra, a long-distance Palearctic migrant that breeds throughout Europe. Whinchat populations are in decline across much of the breeding range (e.g. Britschgi et al 2006; Müller et al. 2005), but the reasons are not completely clear. Previous work suggests that the wintering period may not be a contributing factor (Hulme & Cresswell, 2012). The Whinchat is a great study species for exploring the wider causes of migrant declines as we suspect that their migratory and wintering ecology is similar to other migratory species. Over three wintering seasons we studied survival, site fidelity, habitat use, and migration ecology using geolocators – aspects of wintering ecology which are all very much interlinked.

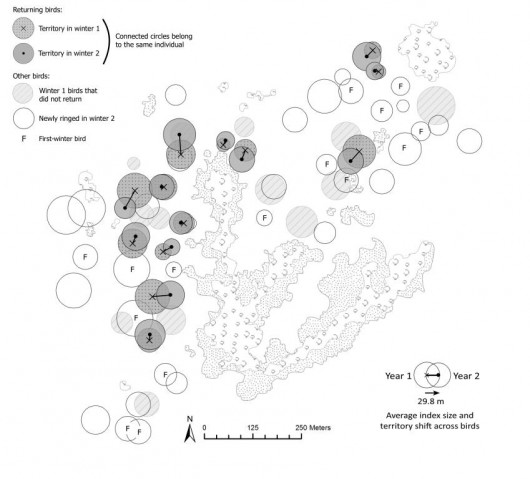

Before we could hope to estimate survival, we had to first establish our ability to detect individuals – specifically returning individuals (the ‘recapture’ part of survival models) – and especially the ability to detect any dispersal that might occur. For migratory birds, this translates to the scale of site fidelity: do individuals maintain a winter territory, and do they return to the same wintering quarters in following years? If they do return, what is the scale – the same region, the same woodland, or to forage from the same bush within the same territory? If a species does not exhibit high site fidelity and winter territoriality or if we cannot reasonably distinguish between whether a bird has died or simply dispersed, then we cannot accurately determine within-winter or annual survival. A previous study in the area by fellow researchers Barshep et al. (2012) had already found that Whinchats hold winter territories and may be highly site faithful, so we were off to a good start.

Whinchats are relatively abundant in Nigeria, and the Jos Plateau where our study took place is no exception. Walking though the small farms and grazing land in the early morning or evening you can find them perched conspicuously on shrubs and maize crops, on a fence post or even on the walls of buildings. Once we identified potential study sites, we set out to capture and colour-ring Whinchats and follow them throughout each winter to address the important question of site fidelity, which would then lead to our survival estimates. In the winter of 2012 we colour-ringed and followed 37 Whinchats and established through high-effort resighting that Whinchats are extremely territorial throughout the winter and hold small, distinct territories. We were able to show that we could accurately detect locally dispersing birds, allowing us to robustly estimate survival. Furthermore, we were able to quantify territory size and explore age and sex differences in within-winter territoriality (Blackburn et al. 2015a).

The following winter we returned to see if we could find any of our previously ringed birds. As soon as I arrived at the research station, I headed to the study site to see what I could find. The first few Whinchats I saw were un-ringed, but then to my excitement I soon spotted a bird with colour rings. Returning the next morning with my territory maps I found that many birds had returned, and amazingly to the very same bushes and fence posts on which I saw them perched last winter. More high-effort resightings revealed that Whinchats had indeed returned to the exact same territories used in previous winters, even if there were other suitable unoccupied territories nearby (Blackburn et al. 2015a). This lack of dominance-based habitat association is an important finding because it suggests that migrants such as Whinchats have relatively general wintering requirements, but are also reliant upon specific wintering sites (reviewed by Cresswell, 2014). We continued to mark and follow birds in the following two winters, studying both within- and between-winter survival.

Over half of the ringed birds returned between years, some for at least three winters, and always to the same territory. Furthermore, we found no differences in survival between first-winter or adult birds, or between males and females. This was mirrored in our findings for small-scale habitat use, site fidelity, and some aspects of departure phenology (Blackburn et al. 2015a, b; Risely et al. 2015). This is very interesting, because we usually expect to see lower survival for juveniles for reasons such as lower experience. Our findings suggest that any higher mortality for juveniles likely occurs during their first migration to the wintering grounds. We saw very high overwinter survival, over 98% at some sites, and also no influence of habitat characteristics on survival. This not only suggests that winter is a relatively stress-free period for migrants, but also that wintering conditions may have a minimal influence on population dynamics, at least for the Whinchat populations we studied, which we now know to breed across Eastern Europe and Russia. Interestingly, we also found that winter residency times differed between birds, with some leaving partway through the winter. Birds that left early were just as likely to return in the following year as those that stayed for the entire winter, suggesting that some birds have multiple wintering areas.

References

Barshep, Y., Ottoson, U., Waldenstroem, J., Hulme, M. & Svensson, S. 2012. Non-breeding ecology of the Whinchat Saxicola rubetra in Nigeria. Ornis Svecica 22: 25-32. View.

Blackburn, E. & Cresswell, W. 2015a. High winter site fidelity in a long-distance migrant: implications for wintering ecology and survival estimates. Journal of Ornithology 1-16. View.

Blackburn, E. & Cresswell, W. 2015b. Fine-scale habitat use during the non-breeding season suggests that winter habitat does not limit breeding populations of a declining long-distance Palearctic migrant. Journal of Avian Biology 46, 622-633. View.

Böhning-Gaese, K. & Bauer, H. G. 1996. Changes in species abundance, distribution, and diversity in a central European bird community. Conservation Biology 10, 175-187. View.

Britschgi, A., Spaar, R. & Arlettaz, R. 2006. Impact of grassland farming intensification on the breeding ecology of an indicator insectivorous passerine, the Whinchat Saxicola rubetra: Lessons for overall Alpine meadowland management. Biological Conservation, 130: 193-205. View.

Cresswell, W. 2014. Migratory connectivity of Palaearctic-African migratory birds and their responses to environmental change: the serial residency hypothesis. Ibis 156: 493-510. View.

Heldebjerg H. & Fox, T. 2008. Long-term population declines in Danish trans-Saharan migrant birds. Bird Study 55: 267-279. View.

Hulme, M. F. & Cresswell, W. 2012. Density and behaviour of Whinchats Saxicola rubetra on African farmland suggest that winter habitat conditions do not limit European breeding populations. Ibis 154: 680-692. View.

Müller, M., Spaar, R., Schifferli, L. & Jenni, L. 2005. Effects of changes in farming of subalpine meadows on a grassland bird, the whinchat (Saxicola rubetra). Journal of Ornithology 146: 14-23. View.

Risely, A., Blackburn, E. & Cresswell, W. 2015. Patterns in departure phenology and mass gain on African non-breeding territories prior to the Sahara crossing in a long-distance migrant. Ibis 157: 808-822. View.

Sanderson, F. J., Donald, P. F., Pain, D. J., Burfield, I. J. & Van Bommel, F. P. J. 2006. Long-term population declines in Afro-Palearctic migrant birds. Biological Conservation 131: 93-105. View.

Vickery, J. A., Ewing, S. R., Smith, K. W., Pain, D. J., Bairlein, F., Škorpilová, J. & Gregory, R. D. 2014. The decline of Afro-Palaearctic migrants and an assessment of potential causes. Ibis 156: 1-22. View.

Image credits

Featured image: Whinchat © Emma Blackburn; Bottom: Emma Blackburn © Chris Murray

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.