Two robins in the same tropical forest: one too many or twice as nice?

LINKED PAPER

Strong asymmetric interspecific aggression between two sympatric New Guinean robins. Freeman, B.G. 2015. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12318 VIEW

Ecological theory predicts that competition for resources can lead to behavioral aggression between ecologically similar species. I investigated interactions between two sympatric New Guinean robin species: Ashy Robin Heteromyias albispecularis and the smaller Slaty Robin Peneothello cyanus.

Tropical cloud forests harbor secrets. Trees festooned with moss and sprays of epiphytes loom out of the mist, their presence felt more than seen. Moisture pervades the air, and the hanging clouds render the forest in grayscale, an effect broken only when sunlight illuminates the forest’s vibrant palette of green. Birds abound in this dark mossy world, but you wouldn’t know it if you don’t listen—you are likely to hear a dozen birds for each individual you observe with binoculars.

Learning birds’ vocalizations is thus a key component of tropical fieldwork. In the remote YUS Conservation Area in Papua New Guinea, I learned some of the common cloud forest birds while setting up a long line of mist-nets on the first day of fieldwork – the high-pitched tinkling of the Friendly Fantail, the “wind-up & water drop” song of Regent Whistlers, the chatter of the Slaty Robin. But despite my best efforts, I was unable to track down the source of the high-pitched modulated whistle that reverberated through the forest.

The next day was the first day of mist netting at a new location, an event akin to Christmas morning for ornithologists. I was especially keen to discover the singer responsible for the piping whistles, and by mid-morning the answer was clear: we had captured dozens of Ashy Robin, a medium-sized insectivore with dark head and white eyebrows. Despite their local abundance, Ashy Robins were devilishly difficult to see outside of the nets. Because I heard its ventriloquist-like song over and over but never saw the singer, I called these birds “ghost robins.”

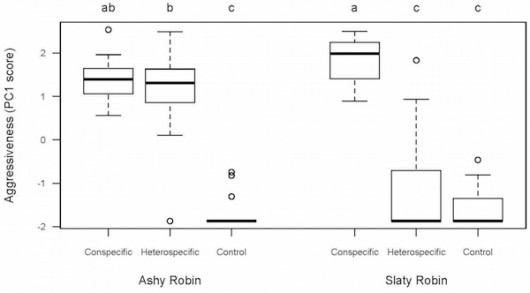

As our team surveyed nearby sites, I noticed that where we mist-netted large numbers of Ashy Robins, the related (but smaller) Slaty Robin was scarce, and that where Slaty Robins were abundant, Ashy Robins seemed less common. I began to wonder if these two robin species might compete with each other for insect food in the understory, potentially explaining why they seemed not to co-occur within the same small patch of woods. I turned to playback experiments to answer this question; if the robins competed with one another, they ought to respond aggressively to each others’ songs. Playback experiments also allowed me to see “ghost robins” in the field for the first time: in response to conspecific playback, Ashy Robins vocalized and then quietly approached the speaker in search of the offending intruder. Moreover, Ashy Robins exhibited the same aggressive behavior in response to Slaty Robin playback (but not Regent Whistler playback, indicating that it was the Slaty Robin song that elicited the aggressive response). In contrast, Slaty Robins responded strongly to conspecific playback, singing repeatedly and flying in to the speaker, but did not respond to playback of Ashy Robin or Regent Whistler songs.

These results were remarkably consistent. Nearly all (22 out of 23) Ashy Robins responded aggressively to Slaty Robin playback, while only a single Slaty Robin (out of 20) responded aggressively to Ashy Robin playback. This asymmetry suggests Ashy Robins are behaviorally dominant over Slaty Robins. Competition isn’t the only explanation for interspecific aggression, however. Aggression can also result from a simple mix-up. If two species look or sound alike, individuals may get confused and respond aggressively to the other species. This appears unlikely to be the case for Ashy and Slaty Robins, which differ dramatically in both plumage and voice. Fieldwork studying “ghost robins” at a second nearby field site shed additional light on this question. Slaty Robins were entirely absent at this new location, such that the Ashy Robins were not interacting with Slaty Robins. Correspondingly, Ashy Robins did not respond aggressively to Slaty Robin playback at this site. Thus, it seems likely that the previously-documented Ashy Robin aggression resulted from crossing paths with Slaty Robins and learning they can aggressively displace this smaller competitor. This interpretation explains why Ashy Robins show interspecific aggression where Slaty Robins are present but not where they are absent.

My study provides compelling evidence for strong asymmetric interspecific aggression between Ashy and Slaty Robins in New Guinean montane forests. In the end, I didn’t have robust enough sampling to statistical demonstrate the distributional pattern that first caught my attention – that where one robin was common, the other was rare – and it seems clear that the “ghost robin” harbors further secrets. Do Ashy Robins evict Slaty Robins from their territories, as the playback experiments suggest is plausible? Is it mere happenstance that Ashy Robin songs are similar to the song of the strikingly beautiful Spotted Jewel-babbler Ptilorrhoa leucosticta, another mid-sized understory insectivore, or might there be further ecological stories to uncover? Whatever the case, the ghost robin doesn’t give up its secrets easily. During months of fieldwork, the closest I ever came to an Ashy Robin without the aid of mist nets or playback was a glimpse of an individual perched on a horizontal twig in the shadowy dawn. It looked at me briefly, then disappeared into the understory.

Further reading

An overview of the birds of the YUS Conservation Area:

Freeman, B, Class, A.M., Mandeville, J., Tomassi, S. & Beehler, B. 2013. Ornithological survey of the mountains of the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 133: 4-18. View.

The natural history of New Guinean birds remains largely unstudied. For example, New Guinea harbors multiple species of poisonous (!) birds – though well known to New Guineans, this phenomena was first studied academically by Jack Dumbacher, who touched his tongue after handling a mist-netted Hooded Pitohui, then noticed his tongue turned numb!

Dumbacher et al. 1992. Homobatrachotoxin in the genus Pitohui: chemical defenses in birds? Science 258: 799-801. View.

Another interesting pattern is that New Guinean montane birds lay exceptionally small clutch sizes—often just a single egg. The strong selective forces driving this extreme pattern remain largely untested.

Freeman, B. & Mason, N.A. New Guinean birds have globally small clutch sizes. Emu 114: 304-308. View.

Boyce, A., Freeman, B., Mitchell, A.E. & Martin, T.E. Clutch size declines with elevation in tropical birds. The Auk 132: 424-432. View.

Evidence that New Guinean montane birds are rapidly shifting upslope associated with recent global warming:

Freeman, B. & Class Freeman, A.M. Rapid upslope shifts in New Guinean birds illustrate strong distributional responses of tropical montane species to global warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 4490-4494. View.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.