Report from a BOU-funded project

Thanks to a small ornithological research grant from the BOU, in October 2021, we set out to deploy six GPS-LoRa tags on migrating juvenile Griffon Vultures (Gyps fulvus) in south-west Portugal. Our main aims for this work were to:

- Test the performance of these tags in a real-world deployment to collect high resolution acceleration and GPS data.

- Improve our understanding of the interactions between Griffon Vultures in and around wind farms in southern Iberia using high resolution GPS and acceleration measurements.

With a view to detecting avoidance or collision events at wind farms, these tags were programmed to record bursts of acceleration data if a force exceeding 3.2g was detected. This threshold was derived from lab tests and analysis of existing tracking datasets.

Large soaring birds are highly susceptible to collision with wind turbines (Oppel et al., 2021) in part because, compared to flapping species, soaring birds are less capable of making sudden changes in trajectory to avoid collisions (May, 2015) and soaring birds often utilise the same wind resource (Marques et al., 2020). Griffon Vultures in particular have been impacted because large numbers of wind turbines have been constructed within migratory bottlenecks for this species in southwest Portugal and Spain (de Lucas et al., 2012; Martín et al., 2018).

Advances in biologging technology are allowing ecologists to gain an unprecedented understanding about the movement behaviour of birds using GPS, Accelerometers and other sensors (Perona et al., 2019). In turn this helps us better understand where conflicts exist between wildlife and human activity which is essential to identify conservation solutions (Frankish et al., 2021).

Two major limitations of deploying tracking devices are cost and weight. In recent years the University of East Anglia has been collaborating on a project with several organisations in the Movetech Telemetry project to develop a low cost, light weight tracking device capable of recording high resolution GPS, accelerometer, temperature, and gyroscope data. The tags forward the data via LoRa (long range) to a LoRa gateway, our ground-based tests demonstrated reliable data transmission from 40km with line of sight. The LoRa tags require very little energy to transmit the data allowing for greater flexibility in battery and therefore tag size. A second advantage of LoRa is that data costs are low because there is no need to have separate data contracts for each device.

Tagging vultures requires patience because you are relying on the birds seeing the meat pile left out for them and then being hungry enough to land. We had eight unsuccessful days where large flocks in the area flew overhead showing little interest in the offerings donated by local butchers. But on day nine, our last possible day to deploy tracking devices on wild birds a whole flock descended, it was quite a sight. Within seconds the meat was gone, highlighting the important clean-up service these birds provide, and several birds were caught in the trap. At one point the team were trying to hold 12 vultures between us. We realised this was too many birds for our team of three people to handle safely hence only four vultures were kept for tagging. Each bird was fitted with colour rings, a metal ring and a GPS-LoRa logger (figure 1 & 2) using a Teflon harness with a weak link designed to allow the devices to safely fall off the birds after a few years. The next day, our final day of field work, we were then able to deploy the remaining two tags on rescued birds rehabilitated by recovery centres.

Figure 1 Eduardo and Carlos deploying a tag on one of the vultures © Jethro Gauld.

Figure 2 A post-release photo of one of the tagged vultures © Jethro Gauld.

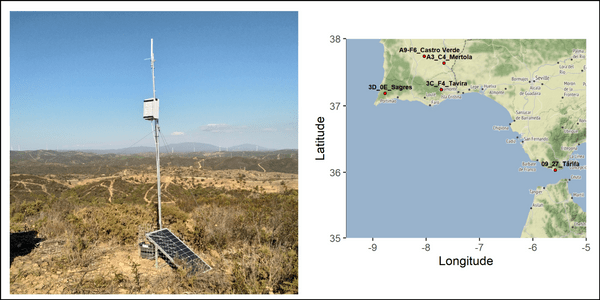

Alongside logger deployment we needed to ensure that there were sufficient LoRa gateways in key areas to receive the data (Figure 3). We installed additional solar-powered LoRa gateways at three locations (Sagres, Tavira and Tarifa) in the migratory areas between southwest Portugal and the Strait of Gibraltar where these soaring birds cross to Africa. These gateways complement the other LoRa gateways deployed by University of East Anglia and ICNF projects in Portugal. The gateways do the job of receiving data from the LoRa devices via LoRaWAN (long range, low power, wide area network) and then forward this via the internet to a data server for download. With time we plan to deploy more gateways to facilitate tracking studies using LoRa.

Figure 3 One of the solar powered gateways alongside the locations of the five LoRa gateways in the region which we manage on our LORIOT server.

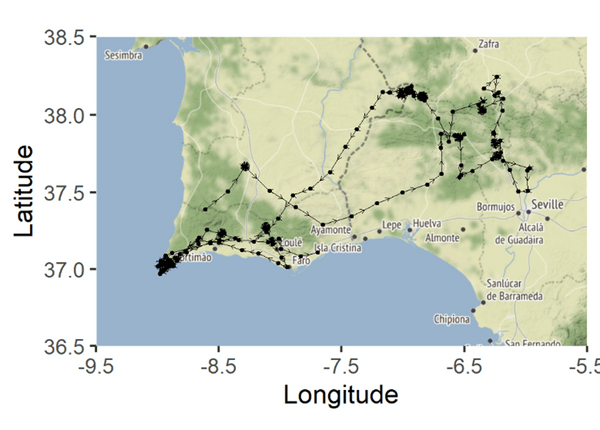

Initial data from the tags has been promising; we have location data for two of the six birds allowing us to plot their movements such as that of vulture 9012_Eduardo (Figure 4) and acceleration data for the other four individuals. One pleasant surprise has been the data transmission range to the LoRa gateways. In the server we can check which data was received by which gateway, enabling us to identify where the bird was when the data was sent. Several transmissions were received from well over 50km distance to the gateway.

Figure 4 Post release movements of vulture 9012_Eduardo between the 25th of October and the 6th of November 202, produced using ggmap and Openstreetmap tiles in R version 4.0.5 © Jethro Gauld.

One lesson learned for future deployments is that these tags prioritise sending acceleration data, hence if the high frequency acceleration recording is triggered by forces exceeding the trigger threshold during fitting the tag or prior to release, large volumes of acceleration data will be stored and sent prior to location data, this was the case for several vultures. The tags can be remotely programmed, so for future deployments the acceleration recording should only be switched on immediately prior to release once the tag is already on the bird.

Now it’s a waiting game for the data to come in, all six birds have been out of gateway range since the 6th of November. We can be relatively certain that two individuals (9DF1_Jethro & 6923_Carlos) have migrated as we received data from them via the Tarifa gateway on the 5th of November and we had reports from our contacts there that large flocks of vultures were crossing the Gibraltar Strait that day. Hopefully in spring they will return within range of a gateway so we can find out where they have been.

The Team

The field work would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr Carlos Pacheco of CIBIO, Eduardo Realinho, Hugo Blanco, Miguel González, the teams at STRIX and ECOSATIVA who kept us informed about the movements of large vulture flocks and Andreas Senn and Marcel Wapper from Miromico. Intermarche de Lagos and Sagres donated meat to the project. Also, thanks to my PhD supervisors Dr Aldina Franco, Dr João P Silva and Dr Phil Atkinson for their guidance and to the wildlife rescue organisations RIAS, CARAS (LPN, Alentejo) and SEPNA/GNR for allowing us to deploy tags on rehabilitated birds.

Funding

Jethro Gauld (Conservation Science PhD student at The University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK) was awarded an ornithological research grant of £2,000 in 2021 for a project entitled ‘Real world trial of new LORA GPS tracking technology to understand vulture movement behaviour at wind farms in three dimensions’.

O Resumo Português

Com financiamento do BOU (British Ornithologists’ Union), Doutorando Jethro Gauld e colegas dele (Carlos, Eduardo e Hugo) fizem um projecto com os Abutres. Eles colocaram seis loggers GPS aos Grifos Gyps fulvus para entender os seus movimentos perto de turbinas eólicas. O outro objective era para entender o desemoenho desses loggers novos. Esses loggers usam LoRa para enviar os dados sobre o posição e atividade do Grifo ao um LoRa gateway. Os resultados preliminares mostram que os loggers enviam os dados ao gateway do uma distancia maior de 50km e tambem que os loggers gravaram GPS e aceleração com sucesso. Agora precisamos esperar para os grifos de voltam em Iberia para ver onde eles foram durante o inverno e tambem seus interaçoès com as turbinas eólicas.

References

Frankish, C.K. et al. 2021. Tracking juveniles confirms fisheries-bycatch hotspot for an endangered albatross. Biological Conservation 261: 109288. VIEW

de Lucas, M. et al. 2012. Griffon vulture mortality at wind farms in southern Spain: Distribution of fatalities and active mitigation measures. Biological Conservation 147: 184-189. VIEW

Marques, A.T. et al. 2020. Wind turbines cause functional habitat loss for migratory soaring birds. Journal of Animal Ecology 89: 93-103. VIEW

Martín, B. et al. 2018. Impact of wind farms on soaring bird populations at a migratory bottleneck. European Journal of Wildlife Research 64: 33. VIEW

May, R.F. 2015. A unifying framework for the underlying mechanisms of avian avoidance of wind turbines. Biological Conservation 190: 179-187. VIEW

Oppel, S. et al. 2021. Major threats to a migratory raptor vary geographically along the eastern Mediterranean flyway. Biological Conservation 262: 109277. VIEW

Perona, A. M., Urios, V. & López-López, P. 2019. Holidays? Not for all. Eagles have larger home ranges on holidays as a consequence of human disturbance. Biological Conservation 231: 59-66. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: “Do you think we’re being watched”? Gyps fulvus, photo taken 20/10/2021 near Bordeira, Portugal © Jethro Gauld.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.