LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

What causes bird-building collision risk? Seasonal dynamics and weather drivers. Scott, K.M., Danko, A., Plant, P. & Dakin, R. 2023 Ecology and Evolution. doi: 10.1002/ece3.9974 VIEW

Every year, hundreds of millions of birds die from collisions with buildings (Fig 1; Machtans et al. 2013; Loss et al. 2014). Migratory birds are particularly vulnerable to fatal collisions (Arnold & Zink 2011; Loss et al. 2014). If you visit a city or suburban home where collisions are common, the number of birds killed will change from day to day. What drives day-to-day variation in collision risk?

Figure 1 Illustration of a bird that has collided fatally with a window. Artwork by Erin Jackson.

To investigate this question, my colleagues Kara Scott and Dr. Roslyn Dakin collected weather data from two major cities, Toronto, Canada and Chicago, USA, where dedicated volunteers from local bird-rescue groups have been monitoring the rates of bird collisions with downtown buildings for decades. Using more than 66,000 collision records across 20 years, the research team set out to quantify how collision risk varies day-to-day for migratory bird species, and how this temporal variation is associated with changes in local weather patterns.

How do collision rates vary day-to-day?

The research team found that urban collision risk has consistent seasonal peaks that match peak migration periods at those two locations. Strikingly, only 12 days were responsible for about 50% of the total collision mortality within a season. This result highlights how certain mitigation strategies, such as turning off the lights, are especially critical during a small number of key dates. If it is difficult to reduce light pollution for the entire migration season, then it may still be beneficial to turn off lights during days with peak collisions.

Do weather patterns drive collision risk?

The team proposed three possible hypotheses by which weather patterns could drive day-to-day fluctuations in bird collisions:

- Hypothesis 1: Calm weather could increase the number of birds in the airspace, increasing collision rates.

- Hypothesis 2: Inclement weather could increase the rate of navigational and flight errors, causing more collisions.

- Hypothesis 3: Clear skies could increase the salience of window reflections, which birds then attempt to fly through.

To test these ideas, they analysed how weather conditions were associated with the daily fluctuations in collision rates above and below the overall seasonal pulse.

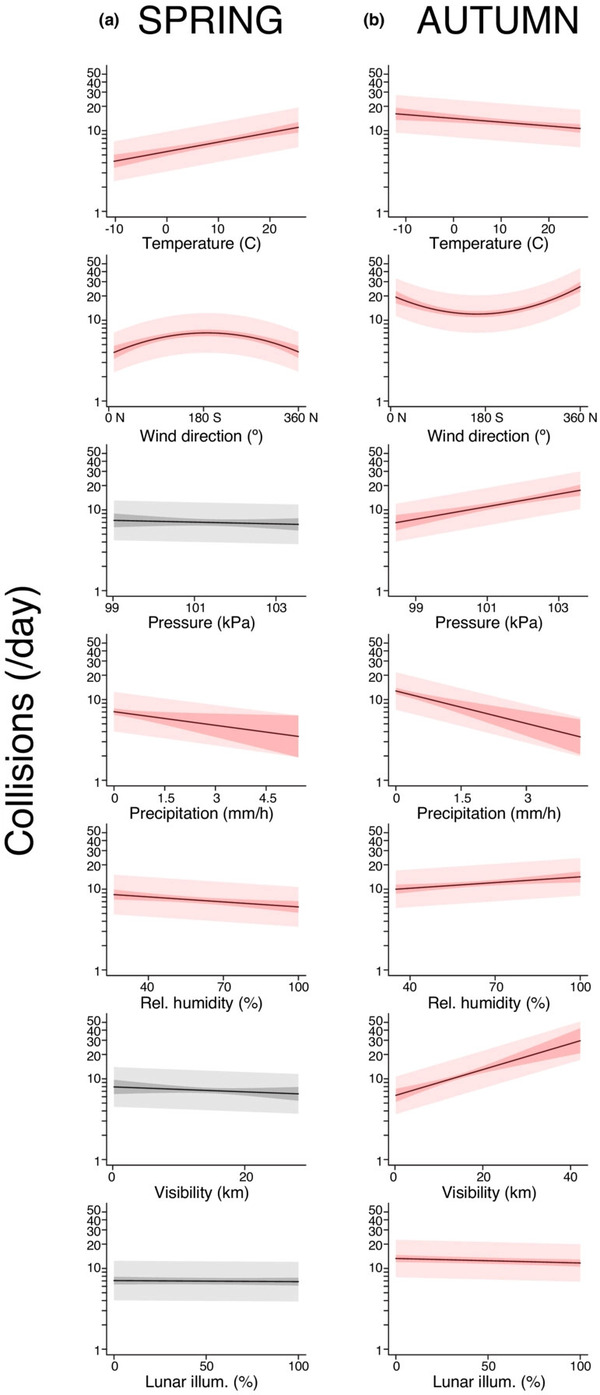

During both the spring and autumn migration periods, collision risk was best predicted by the weather conditions at dawn (Fig 2). During spring migration, the greatest number of collisions occurred on a small number of warm, dry days with winds that were favourable for the direction of northward migration. During autumn migration, the greatest number of collisions occurred on cool dry days with high pressure, high visibility, and winds that were favourable for southward migration.

Figure 2 For both spring and autumn, collisions were best predicted by the weather at dawn. a) In the spring, most collisions occurred on a small number of warm, dry days with winds that were favourable for the direction of northward migration. b) During autumn migration, most collisions occurred on cool dry days with high pressure, high visibility, and winds that were favourable for southward migration.

These findings tell us that collision risk is greatest during a small number of benign weather days that are ideal for migration travel, and that window reflections may be especially risky during autumn. Overall, these findings provide us with a new understanding of how these collisions occur. Crucially, these insights were only possible thanks to the work of hundreds of volunteers over many years from the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors (CBCM) and Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) Canada. These volunteers work towards bird-safe changes to urban design and contributed their efforts in surveying. One of the key next questions is whether similar patterns also drive collision mortality in suburban and residential neighbourhoods.

References

Arnold, T.W. & Zink, R.M. 2011. Collision mortality has no discernible effect on population trends of North American birds. PLoS ONE 6:e24708. VIEW

Loss, S.R., Will, T., Loss, S.S. & Marra, P.P. 2014. Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. Condor 116:8-23. VIEW

Machtans, C.S., Wedeles, C.H.R. & Bayne, E.M. 2013. A first estimate for Canada of the number of birds killed by colliding with building windows. Avian Conservation and Ecology 8:6. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: Bird imprint on window © Ted CC BY SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.