LINKED PAPER

Sex ratio of Western Bluebirds (Sialia mexicana) is mediated by phenology and clutch size. Bartlow, A. W., Jankowski, M. D., Hathcock, C. D., Ryti, R. T., Reneau, S. L., & Fair, J. M. 2021. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12935. VIEW

Female birds can influence the sex ratio in their clutch. Every time I read this ornithological fact, it feels like magic. However, scientists have developed a good understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying biased sex ratios (Nager et al. 1999). From an ecological perspective, there are several explanations for why a mother would prefer more male or female offspring. If the costs and benefits of producing sons or daughters are equal, you would expect an even sex ratio (50:50). But as soon as one sex is more or less costly than the other, selection for a bias can arise. For instance, when one sex tends to help at the nest, it makes sense to produce more offspring of that particular sex (Emlen et al. 1986). Or when the sexes differ in their propensity to disperse, it can be beneficial to have more nestlings of the dispersing sex to reduce competition for limited food (Gowaty 1993). In the Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana), females are the dispersing sex whereas males stick around to help at the nest. Based on the reasoning above, you might thus expect a bias towards males in the nests of these birds.

Large dataset

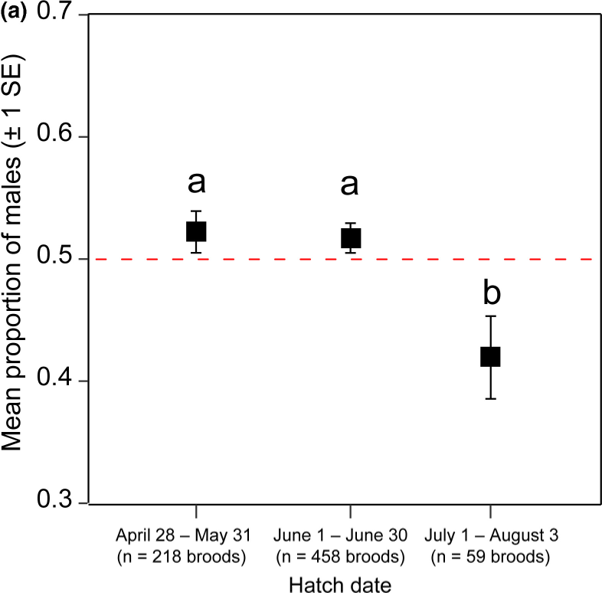

Andrew Bartlow and his colleagues tested this prediction by compiling a comprehensive dataset that spans 21 years (from 1997 until 2017). Analyzing the sex ratios in more than 1000 nests in New Mexico, the researchers found that biases in the number of male or female nestlings could be explained by two main factors: hatching date and clutch size. Birds breeding early in the season produced more sons, while nests later in the season contained more daughters. In addition, small clutches had more sons in comparison to larger clutches which showed a more even sex ratio or more females. These results suggest that it might be beneficial to produce more sons early in the breeding season. The effect of clutch size is probably a consequence of the mother manipulating the sex of the first eggs. This manipulation will be more pronounced in small clutches than in larger ones. For example, if the first two eggs contain males and the remaining eggs are all females, the effect will be stronger in a nest of three eggs compared to a nest with five eggs.

Figure 1. Western Bluebirds produce more sons at the beginning and in the middle of the breeding season. At the end of the breeding season, the nests contained more daughters.

Helping at the nest

The production of sons early in the breeding season supports the idea that mothers prefer males so that they can help out at the nest. Indeed, male Western Bluebirds are known to assist their parents with a second brood during the same year (Dickinson & Akre 1998). However, the findings in this study could also be interpreted in the context of food availability. Towards the end of the breeding season, food sources might have diminished. Hence, it would make sense to produce the sex which disperses in order to avoid direct competition for food. In the Western Bluebird, females are the dispersing sex and the mother might thus preferably produce daughters at the end of the breeding season. And that is exactly what we observe here. Unfortunately, the researchers did not quantify food availability throughout the breeding season and can thus not directly test this hypothesis. More research is needed to understand the magic of biased sex ratios in the Western Bluebird.

References

Dickinson, J.L. & Akre, J.J. (1998). Extrapair paternity, inclusive fitness, and within-group benefits of helping in Western Bluebirds. Molecular Ecology 7: 95– 105. VIEW

Emlen, S.T., Emlen, J.M. & Levin, S.A. (1986). Sex-ratio selection in species with helpers-at-the-nest. The American Naturalist 127: 1– 8. VIEW

Gowaty, P.A. (1993). Differential dispersal, local resource competition, and sex ratio variation in birds. The American Naturalist 141: 263– 280. VIEW

Nager, R.G., Monaghan, P., Griffiths, R., Houston, D.C. & Dawson, R. (1999). Experimental demonstration that offspring sex ratio varies with maternal condition. PNAS 96: 570– 573. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana) | Susan T. Cook | CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here