LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Cosmetic plumage coloration by iron oxides does not confer protection against feather wear. Crespo‐Ginés, R., Gil, J. A., & Pérez‐Rodríguez, L. 2022. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12983. VIEW

Did you know that some bird species take occasional mud baths? You might expect this behaviour from pigs or other mammals, but apparently also Bearded Vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) and Common Cranes (Grus grus) cover themselves in mud (Delhey et al. 2007). Repeated mud baths results in the accumulation of iron oxides – Fe2O3 for the lovers of chemical formulas – on feathers. The benefit of these iron-rich layer remains unknown, although several hypotheses have been put forward, ranging from signaling dominance (Negro et al. 1999) to protection against parasites (Arlettaz et al. 2002). In a recent Ibis study, a team of Spanish researchers focused on another possible explanation: iron oxides might prevent feathers from wearing off.

Experiments

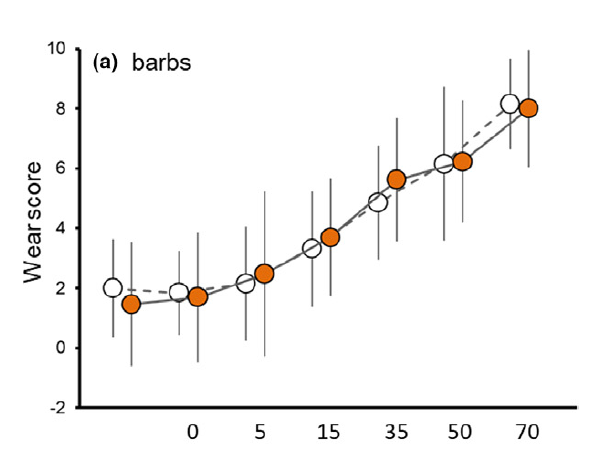

Raquel Crespo-Ginés and her colleagues collected 26 feathers from two dead White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) at the ‘El Chaparrillo’ Wildlife Recovery Centre. Adjacent breast feathers were randomly assigned to two treatments. One group of feathers was stained by immersing them in mud for three minutes, while the other group was treated similarly with water. Next, the researchers repeatedly passed the feathers through a narrow slit lined with sandpaper, mimicking the abrasion of feathers over time. In the end, they compared the degree of feather wear between the two groups (Saether et al. 1994). Statistical analyses revealed no significant differences. No support for the ‘protection against feather wear’ hypothesis.

Figure 1. By pulling the feathers through a narrow slit lined with sandpaper, the feathers wore off. However, there was no significant difference between feathers treated with mud (orange) or with water (white).

Other options

It might be disappointing to see a promising hypothesis disproved, but that is how science progresses. As the Austrian zoologist Konrad Lorenz put it: “It is a good morning exercise for a research scientist to discard a pet hypothesis every day before breakfast. It keeps him young.” Luckily, we still have other competing hypotheses to explain the occurrence of mud baths in birds. Perhaps the iron oxides do not have a protective effect, but rather play a role in camouflage or sexual selection (Delhey et al. 2007). More experiments are needed to unravel this ornithological mystery. At the moment, the situation remains as clear as mud.

References

Arlettaz, R., Christe, P., Surai, P.F. & Møller, A.P. (2002). Deliberate rusty staining of plumage in the Bearded Vulture: does function precede art? Animal Behaviour 64: F1– F3. VIEW

Delhey, K., Peters, A. & Kempenaers, B. (2007). Cosmetic coloration in birds: occurrence, function, and evolution. The American Naturalist 169(Suppl 1): S145– S158. VIEW

Negro, J.J., Margalida, A., Hiraldo, F. & Heredia, R. (1999). The function of cosmetic coloration of Bearded Vultures: when art imitates life. Animal Behaviour 58: F14– F17. VIEW

Sæther, S.A., Kås, J.A. & Fiske, P. (1994). Age determination of breeding shorebirds: quantification of feather wear in the Lekking Great Snipe. Condor 96: 959– 972. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Bearded Vultures (Gypaetus barbatus) | Norbert Potensky | CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here