LINKED PAPER

Sex‐dependent habitat selection in a high‐density Little Bustard Tetrax tetrax population in southern France, and the implications for conservation. Devoucoux, P., Besnard, A. & Bretagnolle, V. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12606 VIEW

Since 1970, the Little Bustard (Tetrax tetrax) has disappeared from ten European countries. In France, this species is still present, but populations have declined dramatically between 1982 and 1996 (Inchausti & Bretagnolle 2005). Clearly, conservation efforts are needed to prevent local extinction of the Little Bustard in western Europe. Designing and implementing successful conservation strategies requires in-depth knowledge of the threatened species. Understanding habitat selection, for example, can help pinpoint crucial locations across a species’ range. Several studies have investigated habitat selection of the Little Bustard, but these studies mainly focused on males which are easier to detect (for example, Delgado et al. 2010). But what if breeding females prefer different habitats? This could greatly alter current conservation strategies. Therefore, a team of French ornithologists studied a population of Little Bustards to figure out whether male and female birds differ in habitat selection.

Sampling

The researchers focused on a study area near the French city Nîmes. There, they counted the number of Little Bustards on a small and a large scale. For the small scale, they used a ‘flushing count’ protocol. Five people walked a transect side by side, keeping ten meters distance between them. When a Little Bustard was flushed out by the advancing line, two experienced observers determined the age and sex of the bird. For the large-scale perspective, the researchers counted the number of displaying males along a transect. Together, these methods provided a fine-scale distribution map of the Little Bustard in the study area. The local density amounted to no less than 50 individuals per 100 hectares, which considerably higher compared to other areas (e.g., 7-16 individuals per 100 hectares in Spain, Morales et al. 2008).

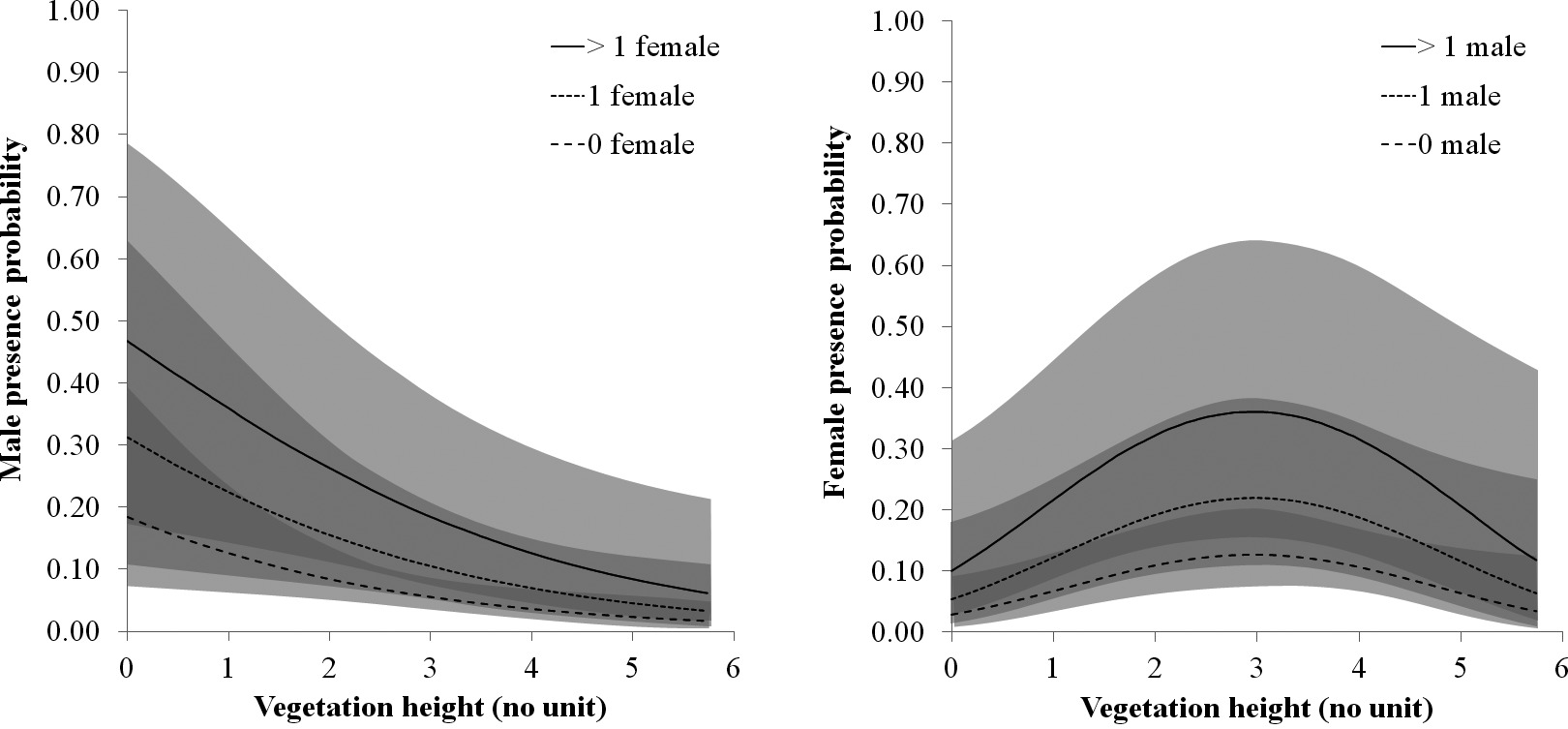

Figure 1 On a small scale, the presence probability of male and female Little Bustards is determined by vegetation height and the presence of the other sex. These graphs highlight the difference between males (left) and females (right).

Exploding leks

Detailed analyses revealed minor differences in habitat selection between males and females. In general, females preferred locations with higher vegetation, probably because this provides more cover to hide from predators and protect their chicks. Furthermore, in both sexes, local habitat selection was positively influenced by the presence of the other sex. This finding can be explained by the mating system of Little Bustards, the so-called ‘exploding lek’ system (Jiguet & Bretagnolle 2014). Displaying males defend little territories that are visited by females. After mating, females tend to raise their chicks in close proximity of the males. It thus makes sense that the sexes are often found in the same habitat.

Mosaic landscape

In contrast to other studies, this survey did not find any sex-specific differences in habitat selection on the larger scale. This could be due to the high density of Little Bustards in the area (50 individuals per 100 hectares). The high number of individuals might force some birds to select suboptimal habitats, thereby leading to less stringent habitat selection. This result does, however, indicate that the study area is highly suitable for Little Bustards. The researchers explain that ‘in recent years, the habitat has largely improved for Little Bustards, as the proportion of fallow land has increased due to land abandonment caused by the decreased financial viability of vineyards and fruit orchards over the last 15 years, and has accelerated since 2005 due to the planned construction of a high-speed railway (construction started in 2014).’ The resulting mosaic landscape composition provides the ideal habitat for Little Bustards to thrive and could be used as an blueprint to guide conservation efforts in other areas (Cornulier & Bretagnolle 2006).

References

Cornulier, T. & Bretagnolle, V. (2006). Assessing the influence of environmental heterogeneity on bird spacing patterns: a case study with two raptors. Ecography 29: 240– 250. VIEW

Delgado, M.P., Traba, J., García de la Morena, E.L. & Morales, M.B. (2010). Habitat selection and density‐dependent relationships in spatial occupancy by male Little Bustards Tetrax tetrax . Ardea 98: 185– 194. VIEW

Inchausti, P. & Bretagnolle, V. (2005). Predicting short‐term extinction risk for the declining Little Bustard (Tetrax tetrax) in intensive agricultural habitats. Biological Conservation 122: 375– 384. VIEW

Jiguet, F. & Bretagnolle, V. (2014). Sexy males and choosy females on exploded leks: correlates of male attractiveness in the Little Bustard. Behavioural Processes 103: 246– 255. VIEW

Morales, M.B., Traba, J., Carriles, E., Delgado, M.P. & García de la Morena, E.L. (2008). Sexual differences in microhabitat selection of breeding Little Bustards Tetrax tetrax: ecological segregation based on vegetation structure. Acta Oecologica 34: 345– 353. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: Little Bustard Tetrax tetrax | Pierre Dalous| CC BY-SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons