LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Morphological divergence among Spanish Common Crossbill populations and adaptations to different pine species. Alsono, D., Fernández-Eslava, B., Edelaar, P. & Arizaga, J. 2020. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12835 VIEW

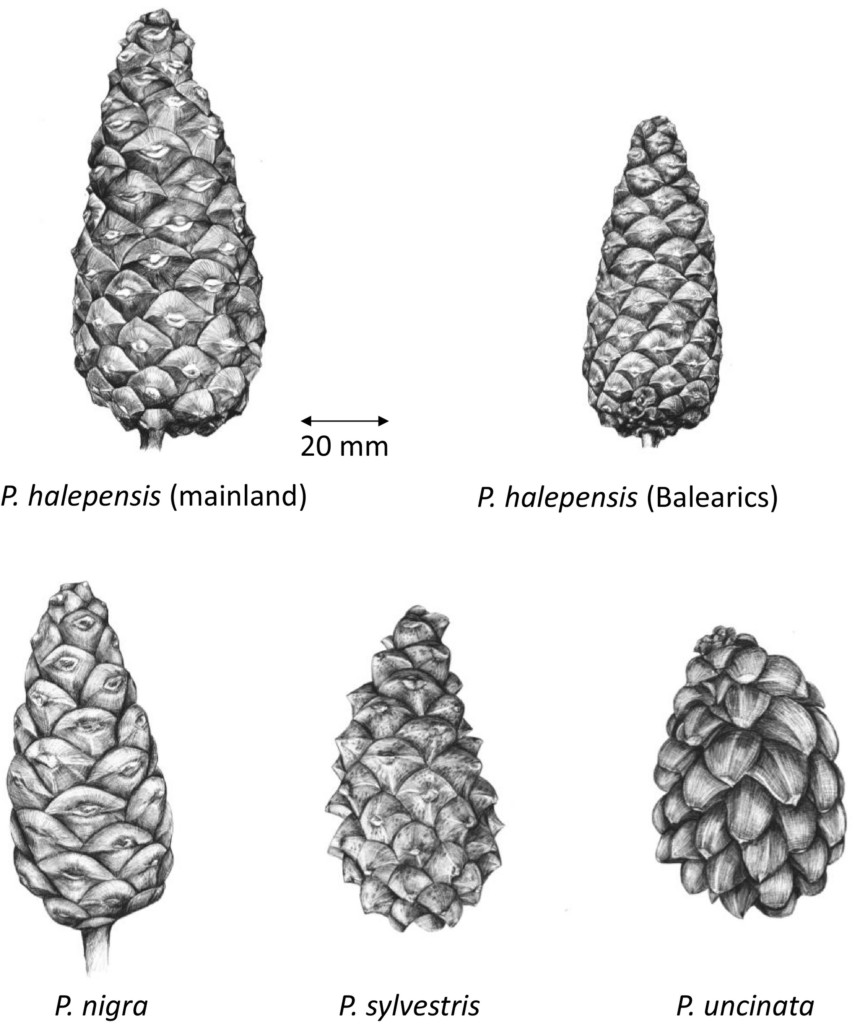

Natural selection gave rise to the mind-blowing diversity in bird beaks. This evolutionary mechanism is simple, but powerful. Imagine a population of common crossbills (Loxia curvirostra) with different beak sizes. Let’s say these birds feed on the mountain pine (Pinus uncinata), a tree that produces seeds hidden inside small cones. Crossbills with a certain beak size can open these cones and access the seeds inside. These cone-opening individuals will be most successful in surviving (they have plenty of food) and producing offspring (they can feed their young). Because beak morphology is heritable, the young birds will inherit the beak size from their parents. Each generation, the variation in beak size will thus be determined by the surviving birds and their offspring. Over time, the average beak size of the population will converge upon the optimal size for cracking the cones of the mountain pine (Benkman 1993).

A clear fit

Theoretically, this story seems plausible, but do we also see these patterns in real life? A recent study tested the prediction that beak morphology and cone size should converge. The researchers used measurements from over 6000 common crossbills from 27 Spanish locations, each dominated by a single pine species. In some cases, there was a clear fit between crossbills and cones. For example, Aleppo pines (Pinus halepensis) have long scales that require a long beak to open them. And indeed, birds feeding on these trees did have proportionally longer beaks. A similar match was uncovered for mountain pines, where the crossbills need a more robust beak to tease apart the thick scales of the cones.

Figure 1. Examples of closed pine (genus Pinus) cones of the four pine species in Spain that are potentially suitable for Crossbills.

Habitat Choice

The situation was less clear for another pine species, the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris). This tree produces relatively small cones and should thus lead to crossbills with smaller beaks. However, the researchers mainly caught birds with large, robust beaks at locations dominated by Scots pine. What could explain this mismatch? One possibility is that crossbills adapted to Scots Pine are absent in Spain. However, birds specialized on other pine species might occasionally visit Scots pines when their seeds are available (Alonso & Arizaga 2017), resulting in a group of crossbills with a variety of beak sizes. Just because a bird is adapted to Aleppo pinecones doesn’t mean it cannot enjoy the fruits of a Scots pine now and then. Some variation in diet is always welcome. Imagine eating the seeds of Aleppo pines your whole life…

References

Alonso, D. & Arizaga, J. (2017). Seasonal abundance patterns of common crossbills Loxia curvirostra L., 1756 in two localities of the Navarran Pyrenees and implications for its survey through ringing. Munibe 65: 95– 105. VIEW

Benkman, C.W. (1993). Adaptation to single resources and the evolution of crossbill (Loxia) diversity. Ecological Monographs 63: 305– 325. VIEW

Image credits

Top right: Common Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) | Frank Vassen | CC BY-SA 2.0 Wikimedia Commons

Blog posts express the views of the individual author(s) and not those of the BOU.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here