Rufous-thighed Kite

© Joao Quental

Web-based biodiversity data reveals a sedentary species is in fact a migrant

LINKED PAPER

Exposing hidden endemism in a Neotropical forest raptor using citizen science. Lees, A.C. & Martin R.W. IBIS. 2014. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12207

The Rufous-thighed Kite Harpagus diodon was until recently regarded as sedentary inhabitant of Neotropical forests. An exhaustive analysis of primarily web-based biodiversity data has revealed that the species is a full migrant, vacating its Atlantic Forest breeding grounds for Amazonian winter quarters.

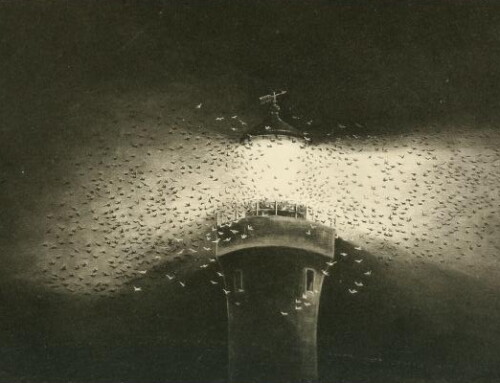

At its most basic level Red List assessment and conservation planning requires accurate knowledge of where species are in space and time. Understanding trends, specific threats etc. is obviously useful in refining those assessments, but at least with accurate land cover maps and a notion of the species’ tolerance to land-use change then you can arrive at a sensible conclusion regarding the likelihood that any given taxon is threatened. One of us (Rob) was until recently charged with updating the vast databases of BirdLife International and a year ago he found himself looking over the distribution information of the Rufous-thighed Kite Harpagus diodon. The literature for this poorly-known Neotropical raptor offered conflicting opinions on its migratory movements; older texts indicated the species to be strictly resident; whilst a slew of recent papers prospered that the species was migratory in the southern parts of its range. Some recent papers assumed year-round residency in Amazonia, whilst others indicated the species to be an austral migrant. Rob fired across a few instant messages to Alex over in Brazil who has a decade of Amazonian field experience under his belt, only to be met initially with the same standard response “partial migrant to Amazonia, resident Guianas, Atlantic Forest….”. “Could it not be a full migrant?” asked Rob. Alex checked the Brazilian photo database WikiAves and low and behold, the past few months of images were ONLY from Amazonia despite the presence of hundreds of images from the Atlantic Forest from earlier in the year (Fig. 1). This was worth investigating!

We hatched a plan to harvest data not only from WikiAves (a site that now has over 1 million bird images archived including Alex’s own kite images e.g. Fig 2) but also digital vouchers from other citizen science initiatives – such as xeno-canto, the Macaulay Library, Fauna Paraguay in addition to documented and undocumented from the literature and data from the fabulous eBird initiative. We also had at our fingertips access to records of specimens from across the world through the ORNIS bird collection site, not to mention historic literature via The Biodiversity Heritage Library. We supplemented this data with requests from and visits to other Museums to catalogue remaining specimens.

Establishing the pattern of austral migration was relatively simple. All records of Rufous-thighed Kites associated with some sort of voucher documentation (specimen, photo, sound-recordings) argued for the fact that the species was a full migrant, breeding in the Atlantic Forest and wintering in Amazonia. However, we also wanted to know whether we could control for variation in observer behaviour as a potential confounding factor AND we wanted to know why it had taken so long for this pattern of migration to be fully uncovered. To answer the first question we compared the spatio-temporal pattern of Rufous-thighed Kites with its sister species, the Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus. It is quite plausible that an absence of records from southern Amazonia might merely reflect a lack of visitation by ornithologists in the height of the rainy season. However, this hypothesis was also easily excluded. In contrast to the pattern shown by Rufous-thighed Kites ornithologists had collected, photographed and sound-recorded Double-toothed Kites across their range throughout the year, providing an extra layer of evidence for the migratory status of its evolutionary sibling.

And why is this not a well-known migration? Why do birders in the Atlantic Forest not celebrate the return of the ‘gavião-bombachinha’ each summer to breed? It seems as though this is because the species is rather cryptic and hard to identify, leading to the pattern having been obscured by confusion with other similar raptor species. By cross-referencing the data from the various sources with the presence or absence of documentation it was clearly noticeable that the out of season reports were almost all undocumented. Perhaps this should not be a surprise. The species is noted for having plumage that appears to mimic that of Bicoloured Hawk Accipiter bicolour, and there are several other similar species to deceive those primed by field guides to believe Rufous-thighed Kite should be present at any given location throughout the year. These potential incidences of misidentification, plus inaccurate specimen meta-data (Fig. 3.) and the widespread (but likely erroneous) notion that most tropical species are sedentary likely also contributed to this misjudgement.

The upshot of the study is that the conservation prospects of the Rufous-thighed Kite must now be reassessed as an endemic of the Atlantic Forest (and pockets of forests of similar physiognomy in the adjoining Cerrado and Yungas biomes) not buffered from extinction by large resident populations in northern South America. We hope that this example serves as a model for the use of multiple biodiversity datasets in addressing ‘Wallacean shortfalls’ in the distribution of poorly-known bird species and we already have our eyes on a few more species that may need a range map makeover!

Blog with #theBOUblog

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.