LINKED PAPER

LINKED PAPER

Landscape and climatic predictors of Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) distributions throughout Kazakhstan. McDonald, G.C.*, Bede-Fazekas, Á.*, Ivanov, A., Crecco, L., Székely, T. & Kosztolányi. A. 2022 Ibis. doi: 10.1111/ibi.13070 VIEW

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Shorebird populations are declining globally in association with a diversity of threats including climate change, predation, human disturbance and habitat degradation (Sutherland et al. 2012, Amano et al. 2020). The Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) is one such shorebird facing global decline (BirdLife International 2019) that has emerged as a model species in evolutionary studies of parental care, thanks to its exceptional diversity in offspring care, where male and female parents either cooperate and care for their precocial offspring together, or one of the parents deserts the family and leaves the burden of care to the other parent (Székely 2019).

While the global Kentish Plover population is declining, the species is currently designated as least concern (BirdLife International 2019). However, their name itself reveals changing distributions. Kentish Plovers no longer breed in the United Kingdom. Indeed, similar to many shorebird species, Kentish Plover populations face continued contraction across Europe, most recently being designated as endangered in Spain (Robles et al. 2021).

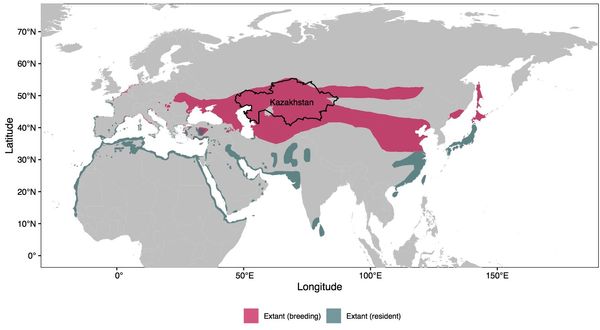

Figure 1 Species distribution range map for Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) showing the breeding (pink) and resident (blue) range from BirdLife International. 2019. Charadrius alexandrinus (amended version of 2016 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22727487A155485165. Accessed on 02 May 2022.

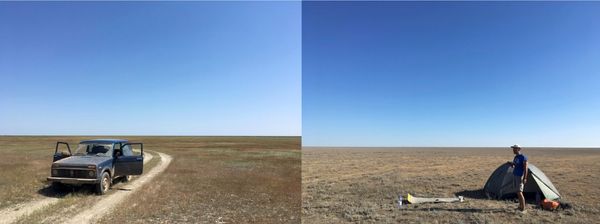

Outside of continental Europe, Central Asia is an assumed core breeding territory for Kentish Plover (Fig. 1), but data in this region are remarkably rare. In 2019 our research team, armed with one Lada Niva (Fig. 2), sought to address this gap and undertook a widespread survey of the breeding population of Kentish Plover across the full extent of Kazakhstan, the largest country in Central Asia and presumed breeding stronghold for the species.

Figure 2 A field biologist and a Lada Niva traverse the Kazakh steppe in search of Kentish Plovers © Grant C. McDonald.

Our survey spanned this transcontinental Eurasian country border to border, and surveyed a diversity of habitats differing in their potential suitability for breeding Kentish Plovers (Fig. 3). We then combined our survey data with spatial information on climate, human settlements, vegetation cover and surface water, and used species distribution modelling to predict the habitats important to Kentish Plover, their potential geographic distribution throughout Kazakhstan and their potential population size.

Figure 3 Diversity of habitats encountered throughout Kentish Plover surveys in Kazakhstan © Grant C. McDonald.

Our results revealed that Kentish Plovers are widespread throughout Kazakhstan, however we predicted remarkably low numbers of individuals for the size of the country, with most likely estimates between 12,000-33,000 individuals. Our analyses underlined that proximity to water bodies, particularly transitory water bodies, is a key predictor of Kentish Plovers presence. Considering that a number of Central Asian regions continue to experience environmental change, including reduced water extent, most notably exemplified by the historic collapse of the Aral Sea that was once the fourth largest lake in the world, our results indicate the key routes via which future climate change may impact on Kentish Plovers numbers.

While determining effective conservation strategies relies on information on the distribution and density of breeding populations, conducting detailed and comprehensive sampling of shorebird populations across vast and inaccessible areas such Central Asia is immensely challenging. Our approach highlights what can be achieved with a small team of field researchers and provides a platform for future studies assessing the status of shorebirds in similarly remote areas of the world.

References

Amano, T., Székely, T., Wauchope, H.S., Sandel, B., Nagy, S., Mundkur, T., Langendoen, T., Blanco, D., Michel, N.L. & Sutherland, W.J. 2020. Responses of global waterbird populations to climate change vary with latitude. Nature Climate Change 1-6. VIEW

BirdLife International. 2019. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Charadrius alexandrinus (amended version of 2016 assessment). In: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22727487A155485165.

Robles, L., Padilla, J., Gómez-Serrano, M., Obeso, J., Tirado, L., Gil, J., García-Ferré, D. & López-Jiménez, N. 2021. Libro Rojo de las Aves de España 2021. 374–375. VIEW

Sutherland, W.J., Alves, J.A., Amano, T., Chang, C.H., Davidson, N.C., Finlayson, C.M., Gill, J.A., Gill, R.E., González, P.M., Gunnarsson, T.G., Kleijn, D., Spray, C.J., Székely, T. & Thompson, D.B.A. 2012. A horizon scanning assessment of current and potential future threats to migratory shorebirds. Ibis 154: 663-679. VIEW

Székely, T. 2019. Why study plovers? The significance of non-model organisms in avian ecology, behaviour and evolution. Journal of Ornithology 160: 923-933. VIEW

Image credit

Top right: A male Kentish Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) © Davidvraju CC BY-SA 4.0.

If you want to write about your research in #theBOUblog, then please see here.