LINKED PAPER

Overland movement and migration phenology in relation to breeding of Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea. Redfern, C.P.F. & Bevan, R.M. 2019. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.12723. VIEW

Arctic Terns, Sterna paradisaea, have one of the longest migrations known, annually moving from breeding colonies within the Arctic Circle to winter in the Antarctic summer, often via a long traverse east across the Indian Ocean (Egevang et al, 2010; Fijn et al, 2013). That much was inferred decades ago from visual observations of birds on migration (Salomonsen, 1967). The development of small geolocation light sensors or geolocators is now allowing us to reveal details of their movements and behaviour away from breeding colonies in unprecedented detail.

The Farne Islands off the Northumberland coast have around 2000 breeding pairs of Arctic Terns. Ringing has shown that breeding Arctic Terns are likely to return each year to the same few square metres of ground. Because geolocators need to be recovered from tagged birds to download the data, this is an ideal site to carry out year-to-year tracking studies on Arctic Terns. To understand the migration ecology of Arctic Terns breeding on the Farne Islands, we fitted geolocators to over 50 breeding adults in 2015 and again in 2017, and were able to retrap 47 birds when the birds returned after a year (or two in some cases), an over-winter return rate of 92.5%.

Figure 1 Geolocator attached to a green plastic (‘Darvic’ PVC) leg ring on an Arctic Tern on the Farne Islands © Chris Redfern

Arctic Terns feed on surface fish and other marine animals. As seabirds, it is easy to assume that the ones breeding on the Farne Islands migrate via coastal or marine routes down the North Sea and through the English Channel on their way south. However, the possibility that some Arctic terns may migrate over the UK has been mooted over the years by many ornithologists.

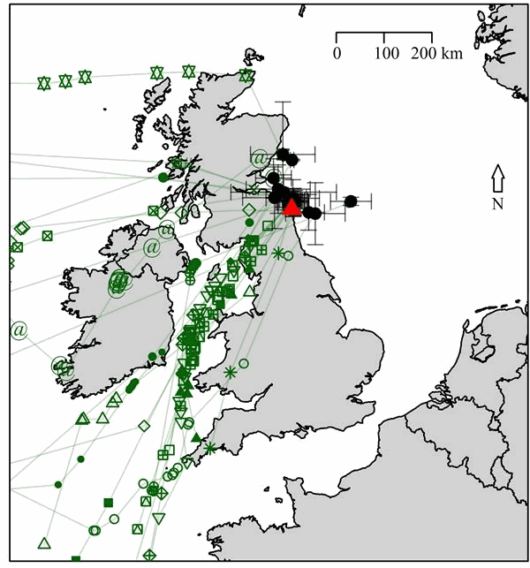

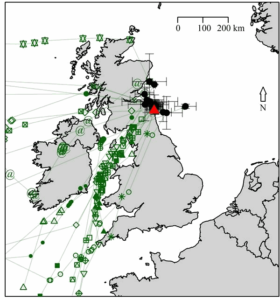

With the geolocator data from 47 individuals, it was now possible to examine the migration routes of Farnes Arctic Terns in relation to the UK. The data reveal that these birds do not appear to migrate down the North Sea at all, but leave and return to the Farne Islands via the Irish Sea, crossing over mainland UK in the process. There are also indications that some birds may also migrate west into the North Atlantic over Ireland. These conclusions (with respect to the UK at least) are supported by an analysis of ‘citizen science’ data from the BirdTrack database assembled by the partnership between the BTO/RSPB/WOS/SOC/BirdWatch Ireland.

Figure 2 An example of geolocation data: geolocation points of Arctic Terns after departure from the North Sea in 2017. The large red triangle is the Farne Islands, Northumberland. The black filled circles with error bars are the last stationary points of individual birds in the North Sea before departure; the green symbols (one symbol per bird) are geolocation points after the last stationary points. Connecting green lines are used to indicate the relationships between points, and are not intended to represent bird trajectories

The geolocator data also allow us to investigate the migration phenology of Arctic Terns in relation to breeding, and show that birds arrive about two weeks before settling down to nest. This is consistent with evidence from studies elsewhere (Bond & Diamond, 2010) that Arctic Terns are ‘income breeders’, developing their eggs from local food resources after they arrive back at the colony.

This study suggests that Arctic Terns regularly migrate across the UK, and this could also apply to Arctic Terns breeding in other colonies in the North Sea and Scandinavia. Land is unlikely to be a barrier to birds that perform annual migrations over many tens of thousands of kilometres each year. We need to be more aware that these and other seabirds may migrate regularly over the UK, and consider the conservation implications of these migration strategies.

Nominate this article for a BOU Science Communication Award.

References

Bond, A.L. & Diamond, A. W. 2010. Nutrient allocation for egg production in six Atlantic seabirds. Can. J. Zool. 88: 1095-1102. VIEW

Egevang, C., Stenhouse, I.J., Phillips, R.A., Petersen, A., Fox, J.W. & Silk, J.R.D. 2010. Tracking of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea reveals longest animal migration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107: 2078-2081. VIEW

Fijn, R.C., Heimstra, D., Phillips, R.A. & van der Winden, J. 2013. Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea from The Netherlands migrate record distances across three oceans to Wilkes Land, East Antarctica. Ardea 101: 3-12. VIEW

Salomonsen, F. 1967. Migratory movements of the Arctic Tern (Sterna paradisaea Pontoppidan) in the Southern Ocean. Biol. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 24: 1-42. VIEW

Image credits

Featured image: A geolocator-tagged Arctic Tern, Sterna paradisaea, flying over its nest site on the Farne Islands in 2017 © Chris Redfern