The lead author of this paper, Ferran Sayol, was awarded a bursary of £2,500 in 2018 to undertake this project.

LINKED PAPER

Brain Size and Life History Interact to Predict Urban Tolerance in Birds. 2020. Ferran Sayol, Daniel Sol,4 and Alex L. Pigot. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00058. VIEW

To thrive in urban environments, birds need to either have large brains, or breed many times over their life, according to a new study by the University College London and Natural History Museum which suggests that birds have two alternative strategies for coping with the difficulties of humanity’s increasingly chaotic cities.

“The expansion of cities is a major driver of biodiversity loss and even extinction, and yet some animals are able to thrive in cities. We hope that by identifying which species are better able to adapt, we can also predict which species may be at risk and how to support them with targeted conservation efforts,” said co-author Dr Alex Pigot (UCL Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research).

“The species that can tolerate cities are important because they are the ones that most people will have contact with in their daily lives, and they can have important effects on the environment within our cities,” he added.

The study’s lead author, Dr Ferran Sayol (University of Gothenburg and the Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre in Sweden) added: “Cities are harsh environments for most species and therefore often support much lower biodiversity than natural environments.”

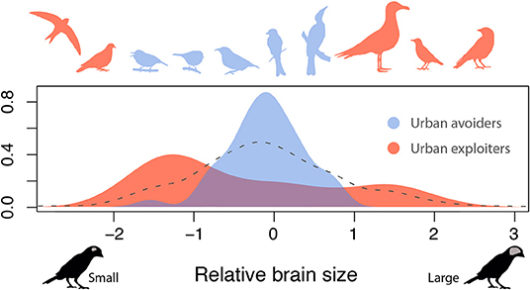

Past studies have shown that birds with larger brains have a number of advantages, such as being better able to find new food sources and to avoid human-made hazards. But researchers haven’t yet been able to explain why some species with small brains – such as pigeons and swifts – also are able to flourish in cities.

To understand what allows birds to adapt to urban life, a research team from Sweden, Spain and the UK analysed databases containing brain and body size, maximum lifespans, global distribution and breeding frequency.

They used existing databases on brain size, complemented with additional measurements in the bird collection of Natural History Museum at Tring, where Dr Sayol spent a week with the support of a British Ornithologists’ Union grant. The research team assembled information on more than 629 bird species across 27 cities around the world.

Their findings confirmed that brain size does play an important role, but it’s not the only path to success.

“We’ve identified two distinct ways for bird species to become urban dwellers,” explained Dr Sayol.

“On the one hand, species with large brains, like crows or gulls, are common in cities because large brain size helps them deal with the challenges of a novel environment. On the other hand, we also found that small-brained species, like pigeons, can be highly successful if they have a high number of breeding attempts over their lifetimes.”

The second strategy represents an adaptation that prioritises a species’ future reproductive success over its present survival. Interestingly, the new research suggests that the two strategies represent distinct ways of coping with urban environments because birds with average-sized brains (relative to their body) are the least likely to live in cities.

These distinct strategies are also less common in natural environments, highlighting the novel challenges posed by urban living. Researchers are working to understand how these adaptations will change the behaviour and structure of urban bird communities in the future.

When considering the impacts of our increasingly urban future on our wildlife neighbours, it will be important to consider both their reproductive strategies as well as their brain sizes.

“In our study, we found a general pattern, but in the future, it could be interesting to understand the exact mechanisms behind it, for instance, which aspects of being intelligent are the most useful. Understanding what makes some species better able to tolerate or even exploit cities will help researchers anticipate how biodiversity will respond as cities continue to expand,” Dr Sayol added.

Image credit

Featured image:An urban House Sparrow | Dixi CC BY SA 3.0 Wikimedia Commons