LINKED PAPER

The causes and implications of sex role diversity in shorebird breeding systems. Székely, T., Carmona-Isunza, M.C., Engel, N., Halimubieke, N., Jones, W., Kubelka, V., Rice, R., Tanner, C., Tóth , Z., Valdebenito, J.O., Wanders, K., McDonald, G. 2023. IBIS. DOI: 10.1111/ibi.13277. VIEW

Shorebirds (or waders as they are often called referring to sandpipers, plovers and allies) are among the celebrities of avian world: their fancy courting displays, their devotion to their cute and fluffy young and their amazing migrations attract the attention of ornithologists, ecologists and behavioural biologists. One of the fascinating aspects of their life is the unusual diversity in their breeding system that spans from monogamy to polygamy whereby either the male, the female, or both sexes may have multiple partners; this diversity has puzzled evolutionary biologists ever since Charles Darwin. A recent review in Ibis tackles the evolutionary emergence of shorebird breeding systems from a novel perspective. Whilst previous attempts to nail down what drives the diverse breeding systems focused on ecological causes such as variation in food availability or the rates of nest failure facilitating the impressive variations in shorebird breeding systems, the recent evidence instead points to social factors.

An international team of shorebird biologists has quantified for the first time the amazing variation in sex role behaviour (i.e., the roles of males and females play in reproduction) that include sexual differences in courtship displays, pair-bonding and parenting. Then the team evaluated multiple research hypotheses as to how this variation may have emerged. Whilst the key data for some of these hypotheses are still patchy, the current evidence points to the role of social environment influencing – perhaps even driving – sex role behaviour. Specifically, the team argues that imbalanced population sex ratios provide different mating opportunities for males and females. For instance, in a population that has more adult males than females, the females may have many opportunities to secure additional partners and increase their Darwinian fitness by being polygamous. The males however, have comparably meagre chances of mating with additional partners and instead increase their Darwinian fitness by taking up parental duties. Conversely, in a population which has more adult females than males, the males should have more opportunities to secure multiple mates and thus become polygamous, whereas the females have lower chances of finding additional mates and are more likely to take up parenting.

Figure 1. Courtship behaviour in Black-winged Stilt (female, left and male, right) © Ryzhkov Sergey.

How the impact of social environment on breeding behaviour works in details, however, has remained a puzzle. It is possible that different physiology of males and females predispose one sex to mature slower into adulthood or have shorter life as an adult than that of the other sex, and these sex differences may precipitate into skewed adult sex ratio (ASR). Indeed, across shorebird species, the adult sex ratios may swing from male-skewed ASR such as 6 male to 1 female to female-skewed ASR, although for a given species, the sex ratios tend to remain consistent. Alternatively, breeding behaviour may impact on male and female mortalities. For instance, shorebird parents are often killed by predators whilst they are protecting the nest or the brood, and so if males provide more care than females – as the case in many shorebirds – then the shortage of adult males could emerge in the population as a consequence of higher male mortality. Teasing apart the tangled web of behavioural, social and demographic effects, and their complex feedbacks has remained a major challenge for further studies of sexual selection, breeding systems and reproductive strategies.

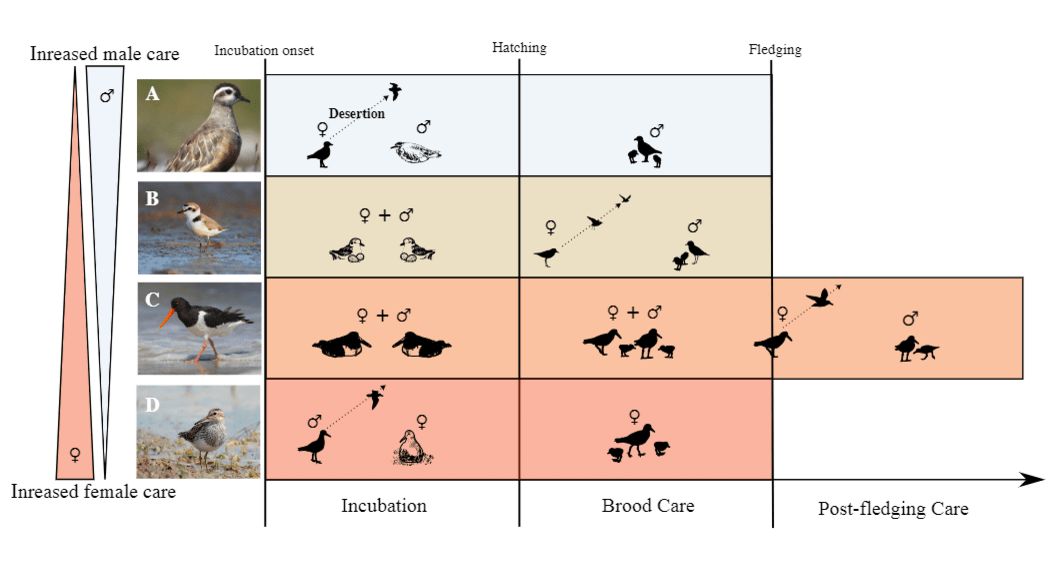

Figure 2. Shorebirds exhibit an unusually diverse parental care systems since the parents can be looked after by the male alone, the female alone or by both parents.

The team, however, also points out that the breeding system of many shorebirds – especially the ones that breed in the tropics or in the southern hemisphere – have not been studied in detail. New studies are urgently needed not only to further advance the evolutionary understanding of breeding habits of these amazing birds but also to assess their populations’ chances in future where humans are throwing unprecedented hurdles into their survival that include habitat loss, hunting and declining breeding success driven by introduced predators and climate change. By combining evolutionary research with conservation-based studies, future research should contribute to the protection of these charismatic birds and will advance our understanding of animal breeding systems.

Image credit

Top right: Two male Ruff © Arjan Haverkamp CC BY 2.0 Deed Wikimedia Commons.